Encountering a New Form of Fiesta Dancers

Virtually every amble we have made to an original indigenous village in Mexico City has brought us surprises: some new experiences, something new learned about Mexican popular (the people's) culture, the culture of el pueblo mexicano.

When we saw an announcement of a fiesta in the Pueblo Santa Úrsula Xitle we were intrigued by two things. First, fulfilling one of our primary criteria, it was a pueblo we had not previously visited and, additionally, it was in Delegación/Alcaldía Tlalpan, the city's largest but one where we had explored only a few of its original pueblos.

Second, the announcement said cuadrillas (qua-DREE-yahs) of arrieros would be performing. In all of our many experiences of fiesta performers, we have seen many types of comparsas (dance troupes) representing various parts of Mexican identity, but never cuadrillas de arrieros. We had seen:

- Concheros (playing lutes) and Azteca (playing drums and rattles) dancers dressed in various styles of indigenous-based attire and celebrating their indigenous identity;

- Chinelos, dancers "disguised", as their name means in Nahuatl, usually wearing masks with blue eyes, pink skin and long, pointed beards, caricatures of colonial Spaniards! However, they are dressed in elaborately decorated, spacious velvet gowns and tall headdresses, and they dance a jumping, spinning, Sufi Muslim dervish-like dance, with their gowns ballooning around them. So, they strike us not just as a caricature of Spaniards, but more as an imaginative, orientalist representation of the Moors, i.e., the North African Muslims who occupied portions of the Iberian peninsula for seven hundred years. They were viewed by the Christian Spaniards as "pagans", and were slowly driven out in the centuries-long "Reconquista", which was completed only in the year 1492. The Spanish Conquista of Mexico and the subsequent "Spiritual Conquest" of its "pagans" began just thirty years later.

- Charros, dressed as Spanish hacendados (ah-cen-DAH-dos), wealthy hacienda (ah-cee-EN-dah, rural estate) owners. Like the chinelos, they are usually masked with Spanish faces that have long beards and dressed in fancy Spanish cowboy attire, elaborately embroidered in gold thread with a wide range of symbols on the fronts and backs of their jackets and pants;

- Caporales (herdsmen) or vaqueros (cowboys), in much simpler, working cowboy attire (think your old "Western" movie, with everyone dressed up for a square dance).

Thus, like charros, cuadrillas de arrieros--as participants in fiestas--are an incorporation of Spanish culture into Mexican popular culture, but they aren't like the elegant charros in their gold-embroidered jackets, tight pants and huge sombreros. They are something more like caporales, an organized group of working-class indigenous and mestizo (mixed indigenous and Spanish) people created to meet the needs of the Spanish ruling class in the Colonial period.

Before the Spanish Conquest, the indigenous had no beast of burden. Men, called tamemes in Nahuatl, carried everything, including members of the upper class, on their backs. After the Spanish took over, they introduced mules and horses — eliminating the need for human carriers. Mules became the "trucks" of cross-country commerce and those who gained the skills to manage mule trains during what could be long trips, called los arrieros, achieved a certain level of increased status.

During Colonial times, the Spanish, after they conquered what is now central Mexico, conquered the Philippines on the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean. In 1513, the Spanish explorer, Vasco Núñez Balboa discovered the Pacific from Panama and declared that it and all lands adjoining it were possessions of the Spanish crown. The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the Philippines in 1521, where he was killed in battle with the resident people. The Spanish explorer, Ruy López de Villalobos, landed there in 1543, and in 1565, the Spaniard Miguel López de Legazpi, sailing from Mexico, conquered the islands. Like Mexico, they became part of the globe-spanning Spanish Empire that endured for some 300 years.

Thereafter, each year, the Spanish sailed what they called the Manila Galleons across the Pacific, bringing goods from China and Japan to the port of Acapulco on the southwest coast of Mexico. From Acapulco, these luxury goods were then carried by mule trains, led by arrieros, 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) up to the pass in the Chichinautzin mountains that form the southern boundary of the Valley of Mexico, and down 3,000 ft. (915 meters) to Mexico City. (See our post Encountering Mexico City´s Many Volcanoes: Giants on All Sides.) From the city, other mule trains carried the goods on to Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where they were shipped to Spain.

Santa Úrsula Xitle, like its neighbor, Chimalcoyotl, and others along the trails leading up the Chichinautzin mountains provided the mules and drivers needed for this arduous trip. Mule drivers worked for Spanish businessmen. So, we wonder why this manifestation of Spanish colonialism is, like charros and caporales, actively maintained and celebrated by the descendants of those who did the actual hard work, essentially as peons on haciendas or low-paid employees of the owners of mule trains.

Why maintain memories of a life of full of hard labor, repressive relationships and poverty? The answer, we surmise, lies in the fact of their awareness that they were an essential link in Spain's global trading network. Without them, that chain from the Philippines to Spain via Mexico would have been broken. So we were most curious to meet these arrieros in the fiesta at Santa Úrsula Xitle.

Reaching Avenida Insurgentes, we turn south and soon find Calle Santa Úrsula. Traveling into the pueblo some blocks, we come to where the road divides, one half turning left, the other to the right. There is no sign of a church. Facing us is a tall wall we cannot see over. Not sure which way to turn, we ask our driver to wait and we get out to ask some people on the street where the church is. They smile and point to the street going to the right and then left, around a corner. We thank them and then our driver, pay him and walk around the corner to the right. Immediately we see people gathered at an entrance in the wall. It is the wall of the church atrio (atrium).

Outside the chapel, we notice two gentlemen wearing cowboy-style sombreros. They appear to be in charge of the proceedings. They introduce themselves as the leaders of two cuadrillas de arrieros, one from Santa Úrsula, the other from Pueblo San Andrés Toltótepec, a short distance south of Pueblo Santa Úrsula and Pueblo Chimalcoyotl, where the climb up the mountains begins to be seriously steep.

At every fiesta, one of our passions is taking retratos, portraits, of the individuals who are participants and the people who make up the audience. Here are some of the arrieros and those attending the fiesta close up.

We thank them profusely for the opportunity and privilege they have provided of being able to attend today's fiesta and photograph it. We tell them we will share our photos via the internet and give them the link to our Facebook page.

Arrieros: Key Links in a Global Trade Route

Before the Spanish Conquest, the indigenous had no beast of burden. Men, called tamemes in Nahuatl, carried everything, including members of the upper class, on their backs. After the Spanish took over, they introduced mules and horses — eliminating the need for human carriers. Mules became the "trucks" of cross-country commerce and those who gained the skills to manage mule trains during what could be long trips, called los arrieros, achieved a certain level of increased status.

During Colonial times, the Spanish, after they conquered what is now central Mexico, conquered the Philippines on the opposite side of the Pacific Ocean. In 1513, the Spanish explorer, Vasco Núñez Balboa discovered the Pacific from Panama and declared that it and all lands adjoining it were possessions of the Spanish crown. The Portuguese explorer Ferdinand Magellan arrived in the Philippines in 1521, where he was killed in battle with the resident people. The Spanish explorer, Ruy López de Villalobos, landed there in 1543, and in 1565, the Spaniard Miguel López de Legazpi, sailing from Mexico, conquered the islands. Like Mexico, they became part of the globe-spanning Spanish Empire that endured for some 300 years.

Thereafter, each year, the Spanish sailed what they called the Manila Galleons across the Pacific, bringing goods from China and Japan to the port of Acapulco on the southwest coast of Mexico. From Acapulco, these luxury goods were then carried by mule trains, led by arrieros, 10,000 feet (3,000 meters) up to the pass in the Chichinautzin mountains that form the southern boundary of the Valley of Mexico, and down 3,000 ft. (915 meters) to Mexico City. (See our post Encountering Mexico City´s Many Volcanoes: Giants on All Sides.) From the city, other mule trains carried the goods on to Veracruz on the Gulf of Mexico, where they were shipped to Spain.

Santa Úrsula Xitle, like its neighbor, Chimalcoyotl, and others along the trails leading up the Chichinautzin mountains provided the mules and drivers needed for this arduous trip. Mule drivers worked for Spanish businessmen. So, we wonder why this manifestation of Spanish colonialism is, like charros and caporales, actively maintained and celebrated by the descendants of those who did the actual hard work, essentially as peons on haciendas or low-paid employees of the owners of mule trains.

Why maintain memories of a life of full of hard labor, repressive relationships and poverty? The answer, we surmise, lies in the fact of their awareness that they were an essential link in Spain's global trading network. Without them, that chain from the Philippines to Spain via Mexico would have been broken. So we were most curious to meet these arrieros in the fiesta at Santa Úrsula Xitle.

Fiesta at Santa Úrsula Xitle

The fiesta at Santa Úrsula Xitle was likely to be a modest one. It was not the pueblo's patron saint fiesta, which is held in October. It was a fiesta sponsored by a cofradía, a brotherhood of parishioners of the church dedicated to venerating la Virgen de San Juan de los Lagos. We had previously encountered this advocación of the Virgin Mary, that is, a manifestation of the Virgin, appearing at a particular time and place and serving as an advocate for the forgiveness of her followers, supplicating for them before her Son, the Christ, and his Father in Heaven. That had been last autumn at the Fiesta de San Francisco in the Quadrante de San Francisco in Delegación Coyoacán, where a conchero comparsa was dedicated to her.

Despite the fiesta's likely modest size, we set off on a Sunday morning in early February to the Pueblo de Santa Úrsula Xitle in Tlalpan, eager to become acquainted with a new pueblo and a new form of fiesta dancer. (The pueblo is the center of a group of colonias that identify themselves as part of the original indigenous village of Xitle. It was named after a nearby, small volcano whose eruption, about the year 100 A.D., destroyed nearby Cuicuilco, the first urban center in the Valley of Mexico.)

Despite the fiesta's likely modest size, we set off on a Sunday morning in early February to the Pueblo de Santa Úrsula Xitle in Tlalpan, eager to become acquainted with a new pueblo and a new form of fiesta dancer. (The pueblo is the center of a group of colonias that identify themselves as part of the original indigenous village of Xitle. It was named after a nearby, small volcano whose eruption, about the year 100 A.D., destroyed nearby Cuicuilco, the first urban center in the Valley of Mexico.)

Although the pueblo is some distance southwest of our base in Delegación Coyoacán, it isn´t difficult for our taxi driver to find. Santa Úrsula lies just south of Tlalpan Centro (the original capital of the altepetl (city-state) of Tlalpan and north of Pueblo Chimalcoyotl, whose fiesta of the Immaculate Conception we attended in December 2017.

Its eastern border is the major Avenida Insurgentes, which crosses much of the city from north to south on its western side. Just south of Santa Úrsula, the avenue merges with the Calzada de Tlalpan to form the Expressway 95D. It follows the ancient trail that climbs over the mountains, and then descends 5,000 feet (1,524 meters) to the state of Morelos and its capital Cuernavaca, and then, more gradually, another 5,000 ft. (1,524 meters) to Acapulco, on the Pacific Ocean in the state of Guerrero. .

Reaching Avenida Insurgentes, we turn south and soon find Calle Santa Úrsula. Traveling into the pueblo some blocks, we come to where the road divides, one half turning left, the other to the right. There is no sign of a church. Facing us is a tall wall we cannot see over. Not sure which way to turn, we ask our driver to wait and we get out to ask some people on the street where the church is. They smile and point to the street going to the right and then left, around a corner. We thank them and then our driver, pay him and walk around the corner to the right. Immediately we see people gathered at an entrance in the wall. It is the wall of the church atrio (atrium).

|

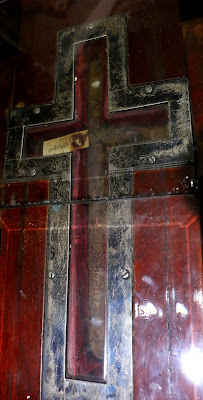

| The original, well-preserved 16th-century Franciscan chapel sits at the far end of the spacious, tree-filled, tranquil, park-like atrio. |

|

| The blue and white papel picado, cut paper, tell us this is a festival dedicated to the Virgin Mary. |

|

| Banner of the Virgen de San Juan de los Lagos of the cofradía (brotherhood) of the Colonia Pedegral de Santa Úrsula, Tlalpan. |

Las Cuadrillas de Arrieros

Outside the chapel, we notice two gentlemen wearing cowboy-style sombreros. They appear to be in charge of the proceedings. They introduce themselves as the leaders of two cuadrillas de arrieros, one from Santa Úrsula, the other from Pueblo San Andrés Toltótepec, a short distance south of Pueblo Santa Úrsula and Pueblo Chimalcoyotl, where the climb up the mountains begins to be seriously steep.

We tell them that our purpose in being here is to get know the pueblo and to take photos to share their fiesta, including the dance of the cuadrillas de arrieros, on the internet via our blog, Mexico City Ambles. We tell them we consider it an honor to be able to witness and record the fiesta and their dance. They invite us to join in the meal being served to participants by a group of women at a table just inside the atrio entrance. We courteously and gratefully accept. It is a simple comida of beef boiled in a broth, accompanied by the indispensable corn tortillas.

When the meal is over, the men of the two cuadrillas line up for their dance. The majority are dressed in the white muslin shirts and pants, some with embroidery, and straw sombreros that were the standard dress for campesinos (rural Mexicans workers) beginning after the Spanish Conquest until the 20th century, that is, for over 400 years. U.S. style "Western cowboy" dress was not adopted until the latter half of the past century.

|

| La cuadrilla de arrieros de Santa Úrsula |

The dance, like those of most comparsas of charros and caporales, is a simple line dance to a basic four-beat rhythm.

The Arrieros Closeup

At every fiesta, one of our passions is taking retratos, portraits, of the individuals who are participants and the people who make up the audience. Here are some of the arrieros and those attending the fiesta close up.

|

| The embroidery says "Cuadrilla de Arrieros Águilas del Sur" Mule Drivers Team Eagles of the South. |

At the end of the dance, the leader of the Santa Úrsula Xitle arreiros introduces us to the mayordomo (chief caretaker) responsible for organizing the fiesta for la Cofradía de la Virgen de San Juan de los Lagos. He introduces himself simply as Fausto, with his wife, Tere.

|

| Tere and Fausto |

We thank them profusely for the opportunity and privilege they have provided of being able to attend today's fiesta and photograph it. We tell them we will share our photos via the internet and give them the link to our Facebook page.

As almost always in our ambles to pueblos and their fiestas, our desire to get to know Santa Úrsala Xitle and to meet and learn about a new group of fiesta dancers, las cuadrillas de los arrieros, has led to an experience full of Mexican ánimo (spirit) and alegría (joy).

And it has led to our learning about a key link, centered here in the pueblos of Tlalpan, in the global trade network that maintained the Spanish Empire for 300 years. The role of los arrieros in that network still gives their descendants mucho orgullo (much pride). It is the same pride we see daily that Mexicans take in mi trabajo, my work, no matter how humble in the economic system it may seem.

By pure chance, we encountered the Arrieros de San Andrés Totóltepec the very next day at the Fiesta of Candelaria in the pueblo of that name in Delegación/Alcaldía Coyoacán. After the main procession and Mass, they sang songs called mañanitas (morning songs, commonly sung on a patron saint's day or an individual's birthday), accompanied by a group of mariachis, to the Virgen de Candelaria in her church. Then they performed their dance outside the church.

And it has led to our learning about a key link, centered here in the pueblos of Tlalpan, in the global trade network that maintained the Spanish Empire for 300 years. The role of los arrieros in that network still gives their descendants mucho orgullo (much pride). It is the same pride we see daily that Mexicans take in mi trabajo, my work, no matter how humble in the economic system it may seem.

Post Script:

By pure chance, we encountered the Arrieros de San Andrés Totóltepec the very next day at the Fiesta of Candelaria in the pueblo of that name in Delegación/Alcaldía Coyoacán. After the main procession and Mass, they sang songs called mañanitas (morning songs, commonly sung on a patron saint's day or an individual's birthday), accompanied by a group of mariachis, to the Virgen de Candelaria in her church. Then they performed their dance outside the church.

|

| Cuadrilla de arrieros from San Andrés Totóltepec sing mañanitas in the Chruch of Candelaria, Coyoacán |

|

| Arrieros de San Andrés Totótepec (left) and Arrieros of another pueblo we didn't manage to identify. |

Clearly, we have only scraped the proverbial surface of cuadrillas de arrieros in Mexico City. We wonder where and when we will encounter them again.

|

Delegación Tlalpan (mustard yellow)

is at the southwest corner of Mexico City. It is just south of Coyoacán (purple), our home, and west of Xochimilco (pink), and Milpa Alta (light yellow). |