Pueblo Iztacalco and San Matías, Its Patron Saint

The second fiesta we attended in Pueblo Iztacalco this year was in mid-May. The first was in mid-April, for the Viernes de Dolores, the Friday of Sorrows, before Palm Sunday. As we wrote in our post, it turned out to be about something completely different, a commemoration of La Viga Canal, central to some three hundred years of the pueblo's life.

This Saturday in May is the pueblo's fiesta for its patron saint, San Matías. St. Matías was a little known apostle or disciple, chosen by lot from followers of Jesus to replace Judas Iscariot. After Judas had betrayed Jesus to the Roman and Jewish powers and Jesus was crucified, he hung himself in remorse. [See our post on the Passion Play of Iztapalapa.] Matías thus restored to twelve the number of central disciples or apostles of Jesus, echoing the twelve sons of the Jewish patriarch, Jacob and the tribes they founded. Matías thus became one of the core group that, after his resurrection, Jesus had charged with spreading the Gospel, the Good News, that his sacrificial death and miraculous resurrection opened the way for sinful mankind to be redeemed and reconciled to God.

San Matías church is the central church of the entire original pueblo. Each of its seven barrios, Santa Cruz, La Asunción, San Miguel, Los Reyes, San Sebastián Zapotla, San Francisco Xicaltongo and Santiago Atoyac, has its own chapel, under the care of the church of San Matías.

|

| Original Pueblo de Iztacalco composed of seven original barrios, outlined by the black boundary line. (Barrio Santiago Atoyac, on the west side, has been divided into north [green] and south [yellow] sections. Pueblo Santa Anita Zacatlamanco [large, light green area on the north side, labeled "El Ranchito"] is a separate, but closely related original pueblo.) Site of Iztacalco's plaza and Church of San Matías, in Barrio Asunción, is marked by green/navy blue star. Line up the middle, south to north, marks the original Canal de la Viga, now the avenue Calzada de la Viga. |

Fiesta Dynamics: Combining the Expected with the Unexpected

- Mexican Fiestas As Sacred Play - Part I: Transforming Culture Thru Play and

- Part II: Fiestas as Creative Acts of Cultural Transformation and Continuity, and

- Ritual As a Vehicle for Sustaining Communal Identity.

With this awareness, we arrive at each new fiesta in each new pueblo expecting to encounter certain predetermined rituals, but also expecting we will encounter surprises in how the communal ánimo of the pueblo's members has, over the years, creatively interpreted and shaped its own, unique variations of those rituals and, thus its unique public identity.

The Paradoxical Interaction of Ritual and Play in the Veneration of San Matías

Iztacalco's fiesta venerating San Matías proved to be a striking combination of ritual and play, one that puzzled, even bewildered us as it slowly unfolded before our eyes. It seemed to present a contradiction between the purpose of the ritual, i.e., the veneration of a patron saint, and the particular persona (from the Greek for mask) chosen as a disfraz (disguise) by the persons carrying it out. It was one that we had never encountered among all the disfraces, such as chinelos (Nahuatl for disguised ones) and charros (fancily dressed Spanish cowboys), we have met. It was a conundrum that took some time for us to come to an insight that, if correct, makes sense of the apparent paradox.

We arrive at the Church of San Matías late on a sunny Saturday afternoon, expecting to witness the traditional procession of the patron saint through the seven barrios of the pueblo. It is scheduled for four o'clock. We know we will not be able to follow the procession its entire length, but we intend to witness its beginning. We find the atrio (atrium) of the church virtually empty. There are no signs of preparation for a procession. We ask a matronly woman leaving the convent adjacent to the church what she may know about the event. She knows nothing. The church doors are closed.

Walking out of the atrio, we ask a man and a woman ambulantes (street vendors) standing by the entrance if they know anything about a procession. We are dubious that these commercially focused folk will be able to help in our religiously focused quest. The man surprises us by saying, "Oh yes, it will begin around the corner, by the side door to the convent."

We thank him for this essential information and walk around the corner of the atrio, into a side street. Down the block, we spy a white van parked and, standing around it, musicians, dressed in black shirts (hot, we think for May's summer-like heat) and white pants and holding their brass instruments. It's a banda, one of the essential ingredients for a procession. We approach them, introduce ourselves and our purpose in being here and confirm that there is to be a procession. After a few minutes, without any visible cue, they start to play. It seems the procession is about to begin, but there are no parishioners in sight, let alone a statue of San Matías. Puzzling.

We thank him for this essential information and walk around the corner of the atrio, into a side street. Down the block, we spy a white van parked and, standing around it, musicians, dressed in black shirts (hot, we think for May's summer-like heat) and white pants and holding their brass instruments. It's a banda, one of the essential ingredients for a procession. We approach them, introduce ourselves and our purpose in being here and confirm that there is to be a procession. After a few minutes, without any visible cue, they start to play. It seems the procession is about to begin, but there are no parishioners in sight, let alone a statue of San Matías. Puzzling.

|

| Strike Up the Band |

A Paradox Makes Its First Appearance

At this point, a man arrives, dressed in a bright yellow tailcoat, black pants and white shoes. He proceeds to complete dressing in his disfraz, putting a red balaclava over his head and pinning a white scarf bordered in red and yellow to the balaclava so it hangs down the back of his neck. He then tops it off (forgive the pun) with a yellow and red top hat decorated with red stars. The piece de résistance is a mask with pale skin, hazel eyes and jewel-studded eyebrows and beard. It is the style of the masks worn by chinelos and charros that are intended to be burlas, mockeries, of upperclass Spanish gentlemen.

We have never before seen such a disfraz at a fiesta. It is that of a European or "Western" upper-class gentleman of the latter half of the 19th century. Why, we wonder, is such a persona part of a patron saint fiesta in a Mexican working-class community? It is a question that will take us some time and thought to answer.

|

| Sporting a red and yellow parasol (literally, "for the sun") dangling more stars, the gentleman heads off down the street, accompanied by the banda playing vigorously. |

Destination Unknown

The "gentleman" and the banda, now joined by a few parishioners in everyday clothing, head off at a rapid pace. We have no idea where they are going or why, but we hurry to keep up with them. After a couple of blocks, we wonder whether we can keep up their pace or will have to resign ourselves to being left behind, in the proverbial "middle of nowhere". We do know the way back to the church, but we will be disappointed to be left out of whatever is happening. Fortunately, while we are considering our dilemma, the group stops to rest and then continues on at a more moderate, and for us, doable pace.

Along the way, a couple of young men, dressed similarly to the "gentleman" in yellow, but in black and white, join the procession (if that's what it is). A young boy, disguised as a charro also joins the group.

|

| Note the Christian Cross. Here is the paradox: expressing one's Catholic faith at the same time one is portraying an upper-class "gentleman". |

A Novel Means for Transporting a Saint

Walking a few more blocks, we all come to the fenced-in entrance of what seems to be some kind of open-air market, but not with the usual individual stalls of the traditional tianguis. A red pickup truck is parked in the entrance gate — its bed ringed with a plethora of fresh flowers, lilies and roses. A portada-style backdrop stands at the head.

We are perplexed and ask one of the parishioners what this is. She tells us that it the anda (platform) that will carry San Matías in the procession. She explains that we will now head back to the church to pick up the saint.

We have seen many variations of andas for carrying saints, from huge, flower-bedecked "floats" born on the shoulders of a dozen or more men and women, to small wooden tables with pole-like handles projecting frontward and backward from the corners for the bearers to carry it, to large tricycles with huge baskets normally used by street peddlers, but we have never seen a pickup truck being used as one. Ingenious and requiring no human muscle.

After a few minutes wait, the truck moves off, followed by the banda, the "gentlemen", a handful of parishioners and us. Fortunately, the truck sets a reasonable pace for us pedestrians. In fact, it seems to be the pace of a procession. We realize that the somewhat hurried walk we have experienced was simply to meet this pickup anda so as to accompany it back to the church. It was a prelude to the actual procession.

A Procession Takes Shape, the Paradox Heightens

We head back to the church, but not by the street we came on. En route, we are joined by a person carrying a banner of San Matías and more "gentlemen". The procession appears to be taking shape as we move along.

|

| Two more "gentlemen" of Iztacalco. Note, again, the Cross. (We love both beards!) |

We note the Christian Cross on the top hats of some of the "gentlemen". If the disfraz of being a "gentleman", like those of being chinelos and imitating charros, is meant to be a mockery of the Spanish, the cross represents the adoption of the Catholic faith those very Spanish brought to the New World.

We have seen this paradoxical combination of ridicule of the Spanish combined with symbols of adherence to the Catholic faith innumerable times on the disfraces of chinelos. Charro symbolism does not, as far as we recall, include explicitly Catholic ones. They are, in most cases, symbols of power borrowed from classic "Western" cultures such as Egypt, Greece, Rome and European royalty, or indigenous or traditional Mexican ones, such as bronco-busting cowboys. (For examples of charro symbolism see our post, Carnaval in Pueblos of Eastern Iztapalapa.)

We have seen this paradoxical combination of ridicule of the Spanish combined with symbols of adherence to the Catholic faith innumerable times on the disfraces of chinelos. Charro symbolism does not, as far as we recall, include explicitly Catholic ones. They are, in most cases, symbols of power borrowed from classic "Western" cultures such as Egypt, Greece, Rome and European royalty, or indigenous or traditional Mexican ones, such as bronco-busting cowboys. (For examples of charro symbolism see our post, Carnaval in Pueblos of Eastern Iztapalapa.)

Arriving at the Church, the Paradox Reaches a Peak

After traveling some blocks, we come out onto la Calzada de la Viga, the four-lane boulevard that replaced the canal in the 1950s. We are a few blocks south of the church.

|

| The Calzada is divided in two by a wide, park-like camellón (median); both sides run north. |

Shortly, we arrive at the plaza. The truck backs up to the curb. The "gentlemen" head for the church on the opposite side of the plaza. In the atrio, an entire group of "gentlemen" is waiting.

|

| Gentlemen in waiting. |

|

| San Matías, in a glass case, is carried from the church on a small wooden anda. |

|

| A small version of San Matías, known as a "demandita", little petition. The size makes him very portable. |

|

| San Matías is carried from the atrio. |

|

| The gentlemen follow. The hat of the second one bears the indigenous glyph of Iztacalco, another curious juxtaposition of cultures. |

|

| San Matías is loaded on his pickup anda. |

|

| The "gentlemen" wait, while San Matías is prepared for his tour through all seven barrios of Pueblo Iztacalco. |

When all is ready, the pickup truck, carrying San Matías, the "gentlemen" and some parishioners start off on the procession. We bid, "Qué te vaya bien," "May it go well for you" and remain behind in the plaza, having expended our energies in the process of the prelude.

So who are these "gentilhombres", and why are they here?

So who are these "gentilhombres" (hen-teel-OHM-bres), these "gentlemen"? The persona, we recognize, is that of a European or "Western" upperclass gentleman of the 19th century and the beginning of the 20th. As we asked ourselves when we saw the first "gentleman" in his yellow top hat and tailcoat, why is such a persona participating in this patron saint fiesta in a Mexican working-class community?

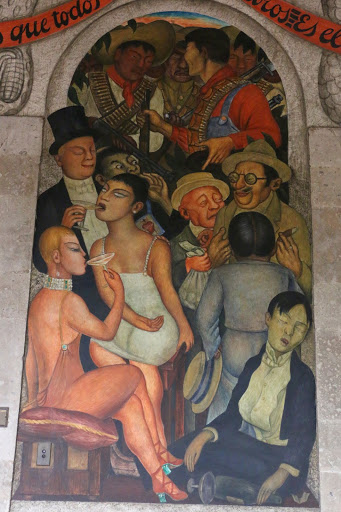

We recall that we have seen this persona before in Mexican imagery, in the work of the Mexican muralists of the post-Mexican Revolution period of the 1920s, Diego Rivera and José Clemente Orozco. (See our series of posts on the complexities and contradictions of the Revolution: Mexican Revolution: Overview of Its Actors and Chapers and The Genesis of the Mexican Mural Movement: The San Carlos Academy of Art and Dr. Atl.)

|

| La Orgia-La Noche de los Ricos The Orgy-The Night of the Rich by Diego Rivera in the Secretariat of Education |

|

| El banquete de los ricos Banquet of the Rich Below the rich are the laboring poor. by José Clemente Orozco in Museo San Ildefonso |

|

| El juicio final The Last Judgement, by José Clemente Orozco. Halos float above the top hats of the gentlemen. God is inebriated and about to lose his grip on the world. This is the left half of the mural. Museo de San Ildefonso |

|

| El juicio final The Last Judgement In the right half of the mural, devils chase the poor away from the presence of God. |

The "gentlemen", sardonically and harshly portrayed by Rivera and Orozco, were, in Mexico, the bourgeois gentlemen of the Porfiriato, the dictatorship of repeatedly reelected president Porfirio Díaz from 1876 to 1911, when the Mexican Revolution took him down. So the image has specific historical and political meaning in Mexico. These "gentlemen" are the quintessential representatives of los de arriba, those from above, the opposite of los de abajo, those from below, the peasant farmers, miners and urban laborers.

Thus, the "gentlemen" venerating the patron saint of an originally indigenous pueblo manifest the paradox at the center of Mexican life and culture, the conflict between indigenous and Spanish worlds continued in class terms of los de arriba vs. los de abajo and the partial reconciliation that has been worked out between them. A major vehicle of this reconciliation has been through a shared Catholic faith, the so-called Spiritual Conquest. Here, in the procession of the patron saint of Pueblo Iztacalco, San Matías, this paradox is displayed with the ironic humor of parody.

The conflicts, contradictions and paradoxes underlying that pragmatic reconciliation remain. The "gentlemen" are a symbolic, communal expression of what is an ambivalent resolution of the paradox. They are a parody of the Spanish and Hipanicized mestizo (mixed race) upper class, a burlesque (Spanish: burla), playfully incorporated into a formal ritual of the Catholic faith, a procession of the saint through his community.

While the "gentlemen", by their ostentatious manner, parody the very personas they are enacting, by their wearing the symbol of the Cross, they signal their true belief in the faith by which the two worlds were joined. Ironically, these upper-class "gentlemen" are venerating a saint who, while he was brought by their cultural forefathers from Spain and imposed upon el pueblo (the people of the indigenous village), over time was transformed by that pueblo into its own, made into a santo popular, a saint of the people. The tables have been turned, at least in this playful parody. Los de arriba are paying honor to the saint of los de abajo.

The use of parody by los de abajo, the working class, with their indigenous roots, to burlesque los de arriba, with their roots in the Spanish Conquest, is quintessentially Mexican. Thus, the "gentlemen" participating in the patron saint fiesta of Pueblo Iztacalco, San Matías, are the perfect ironically playful expression of the paradox at the core of Mexican identity.

"And the haughty man shall be brought down, and the mighty man shall be humbled..." (Isaiah 5:15)

|

Delegación Iztacalco

is the small, dark green area in the northeast of the City, just southeast of Delegación Cuauhtémoc, site of Centro/Tenochtitlan. |

|

| Delegación/Alcaldía Iztacalco with its barrios and colonias. The original Pueblo Iztacalco in marked by the green and yellow star. |