In our effort to visit as many as possible of the original indigenous villages now incorporated into Mexico City, we have, for some time, wanted to visit Tacubaya, in a part of the Delegación Miguel Hidalgo that is to the south of Chapultepec Woods.

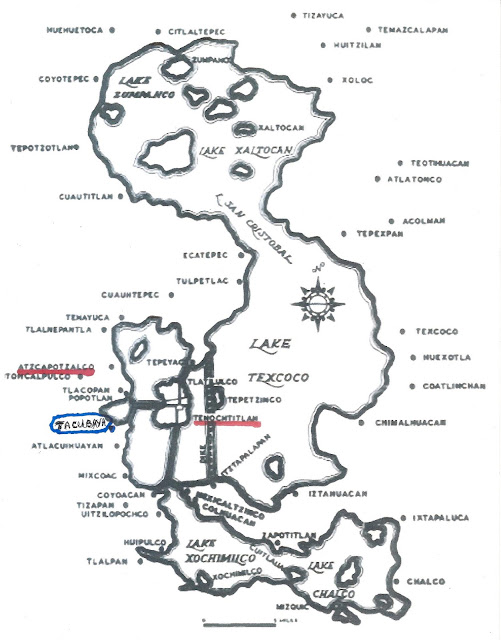

The area has been inhabited since the fifth century BCE. Archeological evidence shows continuous human habitation here since between 450 and 250 BCE by chichimecas, hunter-gatherer tribes. The Mexica tried to settle here in 1276 but then left in 1279. It was renamed Atlalcuihaya by the Mexica of Tenochtitlan when they took control in 1428, after defeating Azcapotzalco, which had dominated the west shore of Lake Texcoco. The name meant “where water is collected.” This name was Hispanicized to Tacubaya by the Spanish. Wikipedia

The area has been inhabited since the fifth century BCE. Archeological evidence shows continuous human habitation here since between 450 and 250 BCE by chichimecas, hunter-gatherer tribes. The Mexica tried to settle here in 1276 but then left in 1279. It was renamed Atlalcuihaya by the Mexica of Tenochtitlan when they took control in 1428, after defeating Azcapotzalco, which had dominated the west shore of Lake Texcoco. The name meant “where water is collected.” This name was Hispanicized to Tacubaya by the Spanish. Wikipedia

We had previously explored Tacuba, another original village north of Chapultepec. However, Tacubaya has a reputation for being a poor, unsafe area, so we were hesitant to go. Recently, on Facebook, there appeared an announcement of a tour of Tacubaya led by a chilango, Mexico City resident. Seeing this as our opportunity to go there with others, we called and made a reservation to join the tour. The following Sunday morning, we took our Line 2 of the Metro north to the Chabacano Station, where we changed to Line 9, which heads west and ends at Tacubaya.

Finding Our Way Through Labyrinths

The Tacubaya station is a labyrinth of long tunnels and many stairways, as three lines cross there, the third being Line 7. We have been in the station before to view the wonderful murals by Guillermo Ceniceros portraying the gods of the Mexica and foundational legends of how in 1225 they came to arrive in the Valley of Anahuac, now the Valley of Mexico.

|

Jade death mask of an indigenous king.

by Guillermo Ceniceros

Tacubaya Metro Station

|

Metro stations have good signage, directing travelers through the correspondencias, connections between one line and another. The leader of the tour has told us to meet him at "the exit to the Periferico (ring road expressway) from Line 1", so we follow the signs leading to Line 1.

When we arrive in the area of Line 1, a large, two-story hall leading to multiple exits, we ask a policeman where the exit to the Periférico is. He seems puzzled but points us in a direction. Farther on, we ask a subway employee where the exit is in order to confirm we are on the correct path. Again, the person seems puzzled by our question, but points us in the same direction.

We exit up some stairs and find ourselves near the entrance to a very large mercado, indoor market, that faces a large plaza mostly covered with concrete, yet containing a few trees, many free-standing puestos, merchant stalls, and a juego mecánico, carnival ride. We ask a couple of the puesto merchants if this is the exit to the Periférico. Again, they seem puzzled, but clearly thinking that we want to go there, indicate that the Periférico is on the other side of the mercado.

It is a few minutes past 10:30, the appointed hour for the tour group to meet, but none of the people standing around the Metro entrance look to be candidates for such an adventure. They are mostly teenagers and adults hanging out on a Sunday morning. Not at all sure we are at the correct exit, but even more unsure about finding an alternative one, we call the tour leader's cell phone. There is no answer. We repeat the call several times over the next several minutes, with the same lack of result.

Going It Alone Through a Labyrinth

Finally, we accept that we are on our own. Since we have made it to Tacubaya, we decide not to waste the trip and to seek out its historic buildings on our own. It is near noon on a Sunday, the safest time to wander about the city, as parents have the day off from work and take their familes out to church, one market or another, maybe to a museum (which are free on Sundays) or just for a paseo, stroll, though some plaza, park or along a tree-lined boulevard.

Our first destination is such a park, the Tacubaya Alameda, and a church likely to be having Mass, the Church of Nuestra Señora de la Purificación, Our Lady of the Purification. This Lady is the Virgin Mary at the moment of her purification forty days after the birth of Jesus, when she presents herself and the infant at the Temple in Jerusalem to be blessed by the priests. Her annual festival, on February 2, is Candelaria (because participants traditionally hold lighted candles), so the church is also better known as la Parroquia de la Candelaria, the Parish Church of Candelaria.

So we approach more merchants and ask directions to the Alameda and church. They point us along one of the multi-lane streets and highways that crisscross the area and tell us that, at a certain point, we will cross a pedestrian bridge. This leads us through what could only be described as another modern-day labyrinth.

|

| Puestos line an underpass beneath a major street. This seems to be the "mens' wear" section. |

Literally every centimeter of the way is lined with puestos, including an underground passageway. Tacubaya is certainly a good example of the muliple ways markets, broadly defined as any place where merchants and customers meet to sell and buy, are realized in Mexico City!

Coming up from underground, we soon spot a pedestrian bridge over yet another multi-lane street. We confirm from a merchant that the bridge leads to the Alameda and the Church.

Tacubaya Alameda

|

| Tacubaya Alameda |

We soon arrive at the Alameda. The Wikipedia article on Tacubaya warns us that the park is "full of drug addicts, alcoholics and garbage", one of the reasons we were leery of coming to the area. But we don't spy any of the three plagues of urban parks (we are familiar with them; we lived in Manhattan in the 1970s). A policeman sits on his motorcycle eating a snack. Parents and children are taking a Sunday morning paseo. In one corner, a group is listening to an evangelical religious sermon. The sidewalks are in excellent condition and the traditional cast iron benches are freshly painted. These are all positive signs the park is currently being cared for by the government of the Delegación Miguel Hidalgo.

In the center is an obelisk honoring the Mártires de Tacubaya, the Martyrs of Tacubaya, soldiers who died fighting for the Reform government against conservative generals who had declared support for the Plan of Tacubaya, a rebellion against the new, liberal constitution of 1857. The generals used Tacubaya, then a village outside Mexico City, as the base for their uprising, which led to the so-called War of Reform (1857-1860). During the War, Benito Juárez became president in exile, returning to the City when the conservatives were defeated.

|

| Benito Juárez' triumphant re-entry into Mexico City, January 1861 Juárez is the middle one of three men in black suits. Painting in the National History Museum, Chapultepec Castle |

Walking through the Alameda, we come to the wide Avenida Revolución, a main north-south Eje, Axis road, and see the wall of the atrio, atrium, of the Church of Candelaria on the other side.

The Church of Candelaria

|

| Church of Nuestra Señora de la Purificación, Our Lady of the Purification, aka Church of Candelaria |

The atrio is a large, tree-filled, quiet retreat from the traffic noise of Avenida Revolución and the barullo, din, of the nearby mercado and ubiquitous puestos. It is one of those classic, tranquil Spanish Colonial spaces hidden within, and in total contrast to, the city around it.

|

| Church atrio |

First Call

As we approach the church door, we hear a single toll of the church bell, followed by a series of tolls. A man standing to one side of the door is pulling a rope that leads upward to the bell tower. As he finishes, we comment, "First Call to Mass." He smiles and nods. We had learned the system of bell tolls when we lived in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, which has many churches, such that bells ring frequently every day of the week.

Our Spanish teacher clarified that they are not marking clock time but are preparatory calls announcing a coming Mass. About twenty minutes before the service is scheduled to begin, a single toll of the bell announced First Call. Ten minutes later, Second Call begins (or depending on local custom, ends) with two tolls; then as Mass begins there is Third Call, initiated or ended with three tolls. All the tolling of the bell that takes place after or before the telltale toll(s) serves for nothing more than getting people's attention.

The sanctuary retains the simplicity of the early churches founded by the religious orders. Our Lady of the Purification is the only 16th century Dominican church remaining in Mexico City. The date 1590 is inscribed into the walls, and in the arches the names of the indigenous peoples who helped in its construction are inscribed: Tlacateco, Huitzilan, Nonohualco and Tezcacuac.

Because of its natural beauty, during the Colonial period, the Spanish came to Tacubaya for respite from the City's Centro. Even after the Mexican War of Independence (1810-20), Tacubaya remained a popular getaway for the wealthy. Many of the well-to-do bought land here for second homes, making the area a summer-home suburb of Mexico City, similar to Mixcoac, Villa Coyoacán, San Ángel and Tlalpan to the south of the city. Across the side street from the church are two of the only such homes we have seen on our amble through what is now mostly a working class commercial area dominated by highways and puestos.

Returning to Avenida Observatorio, and having accomplished all of our goals of the day, we plan to take a cab back to the Metro, as we are tired and don't know how long a walk it would be.

As we walk by the School of Miliary Studies, one of the soldiers we had spoken to on our arrival calls out to us, "¿Comó se fue?"— "How'd it go?" "Muy bien", we call back. "Very well."

At that point, he comes out from the gated entrance and walks over to us. "Where are you going now?" "I'm catching a taxi to get to the Metro."

At my reply, he offers, "Oh, you don't have to do that. The taxi would have to make many turns and the Metro is just down the hill. See that yellow pedestrian bridge (about two blocks away)? Cross over and the mercado is just on the other side. The Metro is just beyond."

|

| Sanctuary As First Call to noon Mass has just been sounded, only a few parishioners are present. We especially love the azulejos, blue tiles of Islamic origin. |

The sanctuary retains the simplicity of the early churches founded by the religious orders. Our Lady of the Purification is the only 16th century Dominican church remaining in Mexico City. The date 1590 is inscribed into the walls, and in the arches the names of the indigenous peoples who helped in its construction are inscribed: Tlacateco, Huitzilan, Nonohualco and Tezcacuac.

|

| "Queen of the Holy Rosary, pray for us." The Virgin Mary and the infant Jesus, also in a simple artistic style. |

Walking along one of the side aisles, we notice a door opening to the outside. Such doors usually lead the way to a patio or inner courtyard surrouded by a cloister, containing monks' rooms above and dining rooms and other common spaces below. Stepping over the threshold, we are not disappointed.

The rooms around the courtyard are still being used by the church, which is not always the case. During the Reform Period (1857-75) and after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917), the cloisters were often taken over by the government as part of its effort to reduce the wealth and power of the Catholic Church. They were put to secular use. Now many are museums or government offices.

Another door leads from the patio out into a side street where we glimpse some interesting buildings.

|

| Colonial Period or 19th century homes |

Because of its natural beauty, during the Colonial period, the Spanish came to Tacubaya for respite from the City's Centro. Even after the Mexican War of Independence (1810-20), Tacubaya remained a popular getaway for the wealthy. Many of the well-to-do bought land here for second homes, making the area a summer-home suburb of Mexico City, similar to Mixcoac, Villa Coyoacán, San Ángel and Tlalpan to the south of the city. Across the side street from the church are two of the only such homes we have seen on our amble through what is now mostly a working class commercial area dominated by highways and puestos.

Returning to the front entrance of the church and passing again through its wonderful atrio, we step out onto Avenida Revolución and into all its modern barullo. Since our next destination is somewhere to the west of the mercado and Metro Station and the church is on the east side, we hail a taxi to avoid any attempt to wend our way on foot through the labyrinth of puestos and highways that lies between them.

Museum of Cartography and the Convent of San José

When we tell the driver who stops for us where we want to go, the Museum of Cartography, he says he doesn't know where it is, but when we say it is at the corner of Avenida Observatorio and the Periférico, he replies, "Está bien"—"That's fine."

We make some turns and are soon on Observatorio, another multi-lane commercial street, heading west. Shortly, we see the two-level Periférico expressway crossing ahead of us. The driver stops and we get out.

We make some turns and are soon on Observatorio, another multi-lane commercial street, heading west. Shortly, we see the two-level Periférico expressway crossing ahead of us. The driver stops and we get out.

In front of us is a very large, two-story building of Neo-classic style, obviously from the 19th century. Mexican Army soldiers are standing guard at the entry gate. We approach and ask if this is the Museum of Cartography, which we know is operated by the Army. They tell us, "No," it is the School of Military Studies. The Museum, they say pointing to an underpass below a Periférico entrance road, is just up Observatorio. Just then we see a sign identifying the museum, so we enter the tunnel.

Coming out of the tunnel, we see some stairs leading up to an ornate metal gate. Climbing the stairs, we come face to face with the museum. Between us is a very attractive brick-paved atrio, but this one is not a peaceful refuge from the city. It is open to the two-level Periférico on one side and the entrance road on the other. Behind us is Avenida Observatorio. We have found a small island of the past in the midst of a contemporary urban sea.

A metal plaque on one side of the atrio tells us its story. Shortly after they arrived in the 1520s, the Franciscans established a "visiting" chapel in Tacubaya, where friars came weekly to administer the Sacraments and teach the indigenous people about Catholicism. This chapel was thus another outpost of the Spiritual Conquest. In 1590, a suborder of the Franciscans, the Order of San Diego, came and built the original convent. dedicated to San José, St. Joseph, Jesus' "godfather", the same saint to whom the first Franciscans who came to Nuevo España in the 1520s had dedicated their homebase convent in Centro. The "Diegans" were the same order that built the Convent of San Diego in Coyoacán, in what is now San Diego Churubusco. In 1686, the order built the church we see in front of us. Shortly afterwards, in the early 1700s, the convent was transferred to the Dominicans.

Closed in the 19th century as part of the Reform expropriations, it was subsequently used by the Army and other government agencies, and even closed at various times. In 2000 the Secretariat of Defense, i.e., the Army, took it over to create the Museum of Cartography which displays many old maps of Mexico City, Mexico and the Caribbean region.

|

| The former sanctuary has the simplicity of the Franciscan churches. |

Returning to Avenida Observatorio, and having accomplished all of our goals of the day, we plan to take a cab back to the Metro, as we are tired and don't know how long a walk it would be.

A Guide Out of the Labyrinth

As we walk by the School of Miliary Studies, one of the soldiers we had spoken to on our arrival calls out to us, "¿Comó se fue?"— "How'd it go?" "Muy bien", we call back. "Very well."

At that point, he comes out from the gated entrance and walks over to us. "Where are you going now?" "I'm catching a taxi to get to the Metro."

At my reply, he offers, "Oh, you don't have to do that. The taxi would have to make many turns and the Metro is just down the hill. See that yellow pedestrian bridge (about two blocks away)? Cross over and the mercado is just on the other side. The Metro is just beyond."

We thank him mucho, adding that we had arrived at that Metro exit by the mercado. This soldier is another example of Mexican amabilidad, kindness, consideration, that we consistently meet on our Ambles around the city, and as we have in our journeys around the country. There is always someone ready and willing to help you out. There is always a guide to show you through whatever labyrinth you may feel you are in.

|

| Delegación Miguel Hidalgo is the dark brown area in the northwestern part of the city. Just west of Cuauhtémoc, the location of Centro Historico. |

|

| Colonias of Delegación Miguel Hidalgo Tacubaya (red and orange star) is at the southern edge, south of Chapultepec Woods (dark green area). |

Tacubaya (green area)

Red/orange star in middle is the Mercado.

Green/yellow star to the right is Church of the Candelaria

(acutally in another colonia).

The Alameda is to its left, across Ave. Revolución.

Mustard/yellow star, upper left, is Museum of Cartography.

Note how crisscrossed the colonia is with major highways and avenues,

making walking around it like a trip through a labyrinth.

Red/orange star in middle is the Mercado.

Green/yellow star to the right is Church of the Candelaria

(acutally in another colonia).

The Alameda is to its left, across Ave. Revolución.

Mustard/yellow star, upper left, is Museum of Cartography.

Note how crisscrossed the colonia is with major highways and avenues,

making walking around it like a trip through a labyrinth.