In the early days of our living in Mexico City, we frequently returned via taxi from Centro Histórico to delegación/alcaldía Coyoacán, where we live, down Cuauhtémoc, one of the main, one-way axis roads. As we traveled through the southern end of delegación/alcaldía Benito Juárez, we would notice what appeared to be a very old, simple, yellow adobe church, mostly hidden behind its atrio (atrium) wall.

|

| Church of Santa Cruz Atoyac, glimpsed from Avenida Cuauhtémoc. The colorful portadas over the entrances to the atrio and the church mark the celebration of a fiesta. |

From its simple style and adobe composition, we thought it might be one of the original Franciscan chapels from the 16th century, a landmark of the so-called Spiritual Conquest by which Franciscans and monks of other religious orders turned the "pagan" indigenous into Spanish Roman Catholics. Some research told us it was the Church of Santa Cruz de Atoyac and that Atoyac had been an originally indigenous pueblo, now almost totally replaced by contemporary commercial establishments and high rise apartment buildings typical of upper-middle-class Benito Juárez. While we eventually explored other original pueblos similarly virtually buried by modernity in Benito Juárez, for a variety of circumstances, it took us until recently to visit Santa Cruz de Atoyac.

Pueblo Atoyac

See our post on the Chapel of the Immaculate Conception in Coyoacán, where we describe how archaeologists recently discovered the earliest settlement in Coyoacán in the area around and under the chapel, built on Hernán Cortés' orders as the first Catholic church in the continental Americas.

At the time of the Spanish conquest in 1521, Atoyac was subject to the rule of Coyoacán, to its south, which was itself part of the territory on the west side of Lake Texcoco previously under the rule of the Tepaneca, based in A(t)zcapotzalco (near the north end of the bay). When the Tepaneca were defeated by the Mexica of Tenochtitlán and their allies, Tlacopan and Texcoco in 1428, they took over all of its territories, including Coyoacán and Atoyac.

After Hernán Cortés, his Spanish troops and indigenous allies defeated the Mexica of Tenochtitlán, on his own initiative, he made grants of land (encomiendas in Spanish) to various of the conquistadores and to indigenous leaders (tlatoani, "speakers", heads of the royal altepetl councils) who had joined him in defeating the Mexica. As the tlatoani of Coyoacán, Ixtoñique, a Tepaneca, had given him access to the causeway to Tenochtitlán for his attack on the city, Cortés granted the area around Atoyac to him. Ixtoñique, baptized a Christian with the name Juan Gúzman Ixtoñique, used the land for grazing sheep introduced by the Spanish for the production of wool. He then delivered a portion of the wool as part of the required tribute to the Spanish.

Over time, as happened all over the Valley and Nueva España, the land was purchased or taken from Ixtoñique's descendants by Spaniards and became a rancho, a small hacienda; that is, a private agricultural estate owned by Spaniards, which it remained, amazingly, until the end of the 19th century. The indigenous pueblo also remained, but with the loss of what had been their communally held and worked land and the intentional draining of Lake Texcoco to prevent the flooding of Mexico City, the villagers were left with no other source of livelihood than to become gañanes (from the Spanish verb ganar = to earn), paid laborers on the rancho.

The area remained rural, a rancho for sheep raising for four hundred years, up until the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917). In the 1920s, the owner sold off his land for its development as an urban residential colonia. This was part of a process of planned urban development that had begun near the end of the 19th century, under the reign of President Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), first farther north, to the west of the original Mexico City (now Centro Histórico).

The Church of Santa Cruz

On the doorway of the chapel of Santa Cruz is engraved the date September 29, 1563. Other documents say the building of the chapel was begun in 1568. At first, because of the limited number of Franciscans, who had begun arriving in Nueva España in 1524, it was a chapel de visita, that is, without resident monks but visited by them on a rotating schedule to preach, baptize the indigenous as Catholic Christians and marry couples as the basis of Christian families. Probably, also at first, like most such chapels de visita, it was an open-air chapel with a large atrio (atrium) where the indigenous would congregate and stand to listen to the preaching and, once baptized, participate in the Mass.

The covered part would have included the altar and baptismal font. Likely, its construction reused already cut stones from a prior indigenous temple. In 1587, a convent was built for a resident monk. Built of adobe (clay), with a straw roof, comfort would have been a challenge in the summer rainy season. Probably, about this time, the full chapel was constructed in the simple Franciscan style it maintains to this day.

|

Church of Santa Cruz Atoyac

The tower was added in the 17th century.

|

|

| Simple sanctuary of the church during Mass. |

In 1529, the Dominicans arrived in Nueva España and began establishing chapels in the Coyoacán area. First to be constructed was San Juan Bautista in the center of Villa Coyoacán, followed by other chapels to the west, away from the lake. Meanwhile, the Franciscans were also establishing churches, such as Santa Cruz in Atoyac, near the lakeshore. At some point in the 16th or 17th century, Santa Cruz Atoyac was transferred to the Dominican order. Competition for control of chapels and, therefore, their pueblos, between the various orders was not uncommon.

In 1569, the Archbishop of Mexico removed the Franciscans from control of their chapels in the four parcialidades (quarters) of San Juan Tenochtitlán and the one in Santiago Tlateloloco and assigned "secular", i.e. diocesan, clergy under his direction. However, in 1571, the leader of the Dominican Order, Fray Fernando de Paz, complained about this to Pope Pius V, who responded by directing the Archbishop to distribute the five churches among the Franciscans, Augustinians and Dominicans.

In the 1750s, the Archbishop of Mexico received permission from the pope to take over all the chapels of the religious orders and place them under the control of "secular", i.e. diocesan clergy. The chapel of Santa Cruz Atoyac was made a chapel of the larger parish of Cristo Rey, Christ the King, in what is now the nearby colonia of Portales. The church was declared an official historical monument by the federal government in 1932. It became an independent parish church only in 1960.

Special sacred objects of Santa Cruz

The Lord of the Precious Blood, the parish's santo popular

|

| El Señor de la Preciosa Sangre. |

The first is a statute of el Señor de la Preciosa Sangre, The Lord of the Precious Blood. He is an avocación, manifestation of the crucified Christ, believed to have been created in the 16th century. However, it is not known when he was brought to Santa Cruz Atoyac, by whom or why he remained there.

Usually, there is a legend attached to the arrival of such sacred statues to a parish and what is perceived as their deliberately choosing the church as their own. This decision is often manifested by their becoming too heavy to be carried away from the church by the people who were carrying them from their home pueblo on a pilgrimage to some other shrine and who stopped at the church to rest overnight. These people readily accept the saint's immovability, or other sign, as miraculous proof of his or her choice of the church as his or her proper new home. The members of the original pueblo often return for the annual fiestas subsequently held to celebrate the date of the choice, concretely manifesting the ongoing connection between the two pueblos.

These sacred figures are usually some avocación of the Virgin Mary or the Christ; that is, an appearance to the faithful in the form of a particular function or moment in their sacred lives in order to serve as an advocate to God the Father or His Son in Heaven for protection from the evils of the world and forgiveness of sins.

These avocaciones (advocates) are, therefore, saints of el pueblo in its double meaning of both the people and the particular village in which they live together. They are santos populares, the people´s saints. Because of this special, intentional choice of a parish as its advocate before the divine Trinity, they become more highly venerated than the church's patron saint that was originally assigned by whatever religious order first established the church in the pueblo. The Virgin of Guadalupe is the most famous of all such santos populares, as she appeared as an indigenous woman to an indigenous peasant in the open countryside and adopted all the people of Nueva España (now Mexico) as her special children.

Although el Señor de la Preciosa Sangre lacks the usual legend attached to his arrival at Santa Cruz Atoyac, by virtue of his physical place in the sanctuary and the intensity of his veneration, with his own fiesta in early January rivaling that of the patron saint fiesta of the Holy Cross on May 3, he is definitely its santo popular.

MCA Note: For more on this very common Latin American Catholic phenomenon of the Christ, the Virgin or other saints miraculously and deliberately choosing a specific home church, see our post: Santos Populares, Popular Saints.As it is, el Señor is not made of heavy wood. He is hollow, made of very light pasta de caña, a paste made from corn stalks. It is believed that the indigenous made statues of their gods from the paste, in place of the stone versions in temples, in order to have light versions to carry into battle. In the 1530s, Don Vasco de Quiroga, a church lawyer and member of the second audiencía, the council established by King Charles to govern Nueva España from 1531 to 1535, was ordained a bishop at the request of the king and archbishop of Mexico in order to bring order to the efforts at conversion and protection of indigenous Purépecha in their territory to the west of Mexica/Azteca territory (now the state of Michoacán).

Don Vasco brought the sculptor, Don Matias de la Cerda, from Spain to instruct indigenous sculptors in the making of Roman Catholic images of the Christ, the Virgin and the various saints. Instead of carving them from wood, they used pasta de caña to produce many of these Christian images. (See more of Don Vasco de Quiroga's history and his saintly veneration in Michoacán in our post: Indigenous Purépecha Traditions of Michoacán Live On In Mexico City.)

El Señor de la Preciosa Sangre is made of such pasta de caña. The delicate, realistic style in which his virtually naked body is composed, producing a profound effect of vulnerability and suffering, leads some art critics to think he may have been created by de la Cerda himself, as it is very much like ones known to have been made by him.

He is also a quintessential version of a "Mexicanized" Christ, where pathos, sorrow and death displace the neoclassic European image of a serene Christ on the cross. This image of the suffering Christ is central to Mexican popular Catholicism, a reflection of their own history of repression, suffering and self-sacrifice.

El Señor de la Preciosa Sangre is also a "black Christ", like the Lord of Calvary in Culhuacán. Black Christs are thought to have originated from what is now southern Mexico and Guatemala and to be reflections of indigenous black gods of the underworld and death. There is a highly venerated Black Christ in a church in southern Michoacán, where Quiroga worked. There is also one in the Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City.

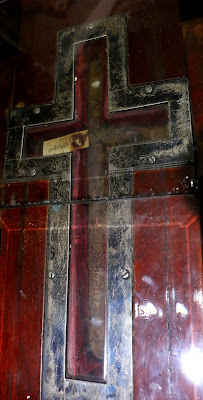

The Holy Cross of Jerusalem

The second holy object in Santa Cruz is a Holy Cross of Jerusalem. These are small crosses ostensibly made from the wood of olive trees from the Garden of Gethsemane, where Jesus prayed after celebrating the Last Supper with his disciples the night of Maundy Thursday. Later that night, he was betrayed there to Roman soldiers, and the next day, Good Friday, he was tried and crucified. There are numerous versions of this Holy Cross of Jerusalem, believed to be encrusted with pieces of the actual cross on which Jesus was crucified and with fragments of the Rock of Agony, on which he prayed in Gethsemane.

One such cross, which had been in the possession of Franciscans in the Curia in the Vatican in Rome, was donated by Pope Pius XII in 1951 to the High Priest of the Basilica of Guadalupe, who was visiting Rome. Brought to Mexico, it was displayed for a short time in the Basilica and then in the Metropolitan Cathedral. It then traveled from church to church throughout the Diocese of the City of Mexico.

|

Initial Visit of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem to Santa Cruz Atoyac in April 1952.Photo provided by Sr. Fernando Elizalde Casas |

Population growth in the area subsequently led church authorities to consider making the chapel of Santa Cruz de Atoyac into a full parish church. At that time, the chaplain of the chapel, Carlos Villaseñor, petitioned the archbishop and the chaplain responsible for the security of the cross that it be permanently placed in Santa Cruz Atoyac. The petition was granted and the cross was placed in the church's care in March of 1959. The following year the chapel was officially designated the Parish Church of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem.

|

| Santa Cruz de Jerusalén |

|

| Cross from wood of olive tree in Garden of Gethsemane |

|

| Fragment of the Rock of Agony encased in center of a silver cross. |

|

| Certificate testifying to the delivery of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem by the Archbishop of Mexico to the Chapel of Santa Cruz, March 13, 1959. |

MCA Note: We are deeply indebted to Sr. Fernando Elizalde Casas for providing us with a copy of the monograph, "La Parroquia de Santa Cruz de Jerusalem: Reseñas históricas y servicios pastorales" | "The Parish Church of the Holy Cross of Jerusalem: Historical Review and Pastoral Services," by Father Arnulfo Hernández H. It is the source for the specific historical information shared here regarding the church and its sacred objects. Creation of this post would not have been possible without the generous contributions of Sr. Elizalde Casas.

The Fiesta of the Lord of the Precious Blood

According to tradition, the statue of el Señor de la Preciosa Sangre arrived at the church the first week of January. Henceforth, a fiesta in his honor is held the weekend of the first Sunday of each year. Its patron saint fiesta, that of Santa Cruz, the Holy Cross, is held on May 3, as it is in every church sharing that patron. We were able to attend the January 2019 fiesta of el Señor de la Preciosa Sangre.

Entering the church atrio from busy Ave. Cuauhtémoc, we find a large group of concheros (so named from their concho, skin, of armadillos traditionally used to cover the backs of their lute-like instruments) engaged in a ritual in preparation for their dancing.

|

| The Holy Cross in the atrio is venerated with indigenous copal incense. |

Two additional banners join that of el Señor de la Preciosa Sangre, identifying where some of the concheros are from:

|

| Santa Cruz Ayotusco is a pueblo in the Municipality of Huixquilucan, in the State of Mexico, just west of Mexico City. |

|

| The "beak" of the headdress is an armadillo skin. |

|

| A group of chinelos, the "disguised ones" in Moorish-like dress, who jump and spin, join the celebration. |

|

| Santiagueros, Warriors of St. James are from Santa Cruz Atoyac. We have seen them at numerous other fiestas reenacting the battle between the Spanish Christians and the Muslim Moors in the Reconquest of Spain, which became a rehearsal for the Spanish Conquest of the Americas. (For their full performance see: Santa María Tepepan, Xochimilco: Part I - Drama of the Christians vs. the Pagans) |

|

| The procession of the saints through Pueblo Santa Cruz Atoyac begins. |

|

| San Sebastián from Pueblo San Sebastián Xoco (HO-ko), (Xocotitlan, southwest of Atoyac on the map of the bay above.) |

|

| Banners of Pueblo San Simon Ticumac, originally an island pueblo directly east of Atoyac and Church of St. John the Evangelist, which is just north of Mixcoac (see below). |

|

| Banners of Pueblo Mixcoac, directly west of Atoyac, with Image of the Virgin of Candelaria and Infant Jesus and Church of San Lorenzo Xochimanca, in what is now called Colonia Tlacoquemécatl, which was actually yet another pueblo just north of Xochimanca. Both are just north of and between Mixcoac and Santa Cruz Atoyac. |

|

| The honoree of the day. |

Pueblos Holding Onto the Survival of their Identity

As we watch this rather small procession, with a few statues of saints and a number of banners representing saints of other pueblos that are neighbors of Santa Cruz Atoyac, all of which we have previously visited, we realize we are watching an assertion of the continuing existence of the identity of virtually every original pueblo now incorporated within the Delegacíon/Alcaldía of Benito Juárez.

The delegación is an historical newcomer, created in 1970. It was one of four new delegaciones (boroughs) formed by dividing up what had been the Central Department of the Federal District. The Central Department had, itself, been formed after the Mexican Revolution, in 1928, along with twelve delegaciones to compose the District. In 1941, the Central Department was renamed "Mexico City".

The Central Department/Mexico City and the delegaciones were a synthesis and replacement of a large number of long-standing Spanish-style municipalities, consisting of a cabacera (literally, head town), municipal seat and numerous dependent pueblos that had been subsumed into the Federal District is the mid-1800s. These municipalities, in turn, had been indigenous altepetls (city-states) before the Spanish Conquest. The pueblos represented in today's fiesta were communities subject to one or another of these ancient altepetls. In this long-range historical context, Delegación Benito Juárez is an anomaly. The pueblos are the norm. (See our page: How Mexico City Grew From an Island Into a Metropolis.)

The Central Department/Mexico City and the delegaciones were a synthesis and replacement of a large number of long-standing Spanish-style municipalities, consisting of a cabacera (literally, head town), municipal seat and numerous dependent pueblos that had been subsumed into the Federal District is the mid-1800s. These municipalities, in turn, had been indigenous altepetls (city-states) before the Spanish Conquest. The pueblos represented in today's fiesta were communities subject to one or another of these ancient altepetls. In this long-range historical context, Delegación Benito Juárez is an anomaly. The pueblos are the norm. (See our page: How Mexico City Grew From an Island Into a Metropolis.)

The average chilango (Mexico City resident) thinks of Benito Juárez as a modern, upscale, yuppie part of the city, but these pueblos represent its true origins and they continue to make their ancient presence known. Their manifestation at today's fiesta may be modest, but it says,

"We were here long before not only Delegación Benito Juárez was created, but long before Mexico City came into being with the Spanish Conquest of Tenochtitlán. And we are still here."

|

Delegación/Alcaldía Benito Juárez (bright yellow)

sits south of Cuauhtémoc, site of Centro Historico,

and north of Coyoacán.

|