Here we begin a series of posts devoted to our ambles through the pueblos originarios, the original, indigenous neighborhoods and villages of Mexico City. Today they are simply islands surrounded by the modern urban sea, most of them more or less hidden from the view of outsiders.

To understand the dynamics of the confrontation between and subsequent synthesis of indigenous, Mesoamerican, and Spanish worlds, we don't start our tour with the now-hidden indigenous neighborhoods of Tenochtitlan or the first villages around the lake which the Spanish Catholic friars entered to implement the cultural transformation known as the Spiritual Conquest.

We begin, instead, with the most potent, quintessential embodiment of this process of Mexican reincarnation:

Tonantzín is a manifestation of the Earth Mother, who was also known as Coatlicue, the mother of all living things. Conceived by immaculate and miraculous means, Tonantzín, or Little Mother, was the patronness of childbirth. In Mesoamerican culture, the earth was both mother and tomb, the giver of life and the receiver of human remains as they decomposed to rejoin the Life Force. Hence, the goddess was also the one to decide the length of life given to a person. As a primary force in human life, she had a devout following.

A Vision Transforms a People and Their Culture

According to tradition, on a Saturday, December 9, 1531, ten years after the fall of Tenochtitlán, Juan Diego, a Náhuatl peasant who had been baptized as a Roman Catholic Christian, was passing by the hill of Tepeyac headed toward the causeway to get to the Franciscan mission at Tlatelolco for religious instruction and to perform various religious duties. He was stopped by the appearance of a young, morena, brown-skinned, woman who addressed him in Nahuatl, his native language. She was clearly one of his own, indigeous people.

She identified herself as Mary, the ever-virgin Mother of God, and instructed him to request that the bishop erect a chapel in her honor at that spot, so she might relieve the distress of all those who call on her in their need.

Juan Diego went into the Center of Mexico City, and reported his vision to the bishop, Fray Juan Zumárraga, who told him to come back another day, after he had had time to reflect on what he had been told.

However, during that night, Juan Diego's uncle, Juan Bernardino, fell seriously ill and Juan Diego was obliged to attend to him. In the very early hours of Tuesday, December 12, Juan Bernardino's condition having deteriorated overnight, Juan Diego set out for Tlatelolco to summon a priest to hear Juan Bernardino's confession and administer the Last Rites to him. In order to avoid being delayed by the Virgin and embarrassed at having failed to meet her on Monday as agreed, Juan Diego chose to go around the opposite side of the hill.

Obeying her, Juan Diego found an abundance of flowers unseasonably in bloom on the rocky outcrop where only cactus and scrub normally grew. Using his open mantle as a sack (with the ends still tied around his neck), he returned to the Virgin; she re-arranged the flowers and told him to take them to the bishop.

On gaining admission to the bishop in Mexico City later that day, Juan Diego opened his mantle, the flowers poured to the floor, and the bishop saw they had left on the mantle an imprint of the Virgin's image, which he immediately venerated.

The next day, December 13, Juan Diego found his uncle fully recovered, as the Virgin had assured him, and Juan Bernardino recounted that he, too, had seen her at his bedside; that she had instructed him to inform the bishop of this apparition and of his miraculous cure; and that she had told him she desired to be known under the title of Guadalupe. The bishop kept Juan Diego's mantle first in his private chapel, then in the cathedral on public display where it attracted great attention.

Virgin of Guadalupe, Mother of All Mexicans

The reported appearance of the Virgin of Guadalupe to the recently-baptized Náhuatl peasant Juan Diego—and its combined acceptance by indigenous converts and the Catholic clergy—became the single most powerful unifying factor between the two peoples and their cultures. The conquered indigenous people identified the dark-skinned Virgin who spoke in Náhuatl with the mother goddess Tonantzín and celebrated her with indigenous-tinged rites within the framework of the Catholic Church's veneration of the Mother of the Son of God.

The Virgin of Guadalupe was also embraced by the Spanish criollos, pure-blooded Spanish born in Nueva España, rather than in Spain. The Virgin´s personal appearance on Mexican soil was seen as establishing a sacred relationship between their actual homeland and their cultural homeland, Spain. Mestizos, those with mixed indigenous and Spanish blood, who were essentially outcasts from both cultures, found in the Virgin not just the recognition, but the very embodiment and, thus, sanctification and reconciliation of their conflicted heritage.

Six Churches of the Basilica Complex

Tradition says that in response to the request of the Virgin to build her a chapel at the foot of Tepeyac Hill, in 1536, Bishop Fray Juan Zumárraga replaced an original temporary shrine with a church, This was replaced in 1622 by a larger church, which, in turn was replaced by a third at the beginning of the 18th century which still stands and is known as the Old Basilica.

Meanwhile, four other churches and chapels were erected around the base and atop the small hill. Most recently, in the 1970s, as the Old Basilica was both badly damaged by sinking into poor subsoil and earthquakes and too small to accommodate the faithful for the December 12 Fiesta of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a new Basilica was built.

Here we amble around the five churches:

Antigua Basilica: The Old Basilica stands on the site of the first church, built around 1536. According to tradition, its construction was ordered by Bishop Fray Juan Zumárraga to comply with the Virgin's command. In 1622 the original church was replaced by a second structure that was, in turn, replaced between 1695 and 1709 with this Baroque-style structure, which remained in use until 1974. But this building lies, in part, over the old lake bed; consequently, there was considerable structural damage as the old lake bed continued to settle. The damage was such that a new Basilica had to be built. The old one then subsequently underwent extensive repair.

Parroquia de Indios: Parish Church of the Indians, where the indigenous could worship. According to tradition, it is built atop the foundation for the ancient Mexicas-Aztec Temple of Tonantzín.

Along the way, you pass a reminder of the indigenous foundations of Mexico:

To understand the dynamics of the confrontation between and subsequent synthesis of indigenous, Mesoamerican, and Spanish worlds, we don't start our tour with the now-hidden indigenous neighborhoods of Tenochtitlan or the first villages around the lake which the Spanish Catholic friars entered to implement the cultural transformation known as the Spiritual Conquest.

We begin, instead, with the most potent, quintessential embodiment of this process of Mexican reincarnation:

Tepeyac and Its Temple to Tonantzín, the Earth Mother

|

| Tepeyac (circled) lies on the shore of Lake Texcoco, just north of Tenochtitlan and Tlatelolco, to which it was connected by a short causeway. |

Before the Spanish arrived in the Valley of Anahuac, one of the multitude of temples around the lakes was located on a hill in the capulli, village of Tepayac. Located on the shore of Lake Texcoco, north of and across a narrow channel in the lake from Tenochtitlan, Tepayac was linked to Tenochtitlan by a causeway that passed through Tlatelolco. The temple was dedicated to the goddess Tonantzín.

Tonantzín is a manifestation of the Earth Mother, who was also known as Coatlicue, the mother of all living things. Conceived by immaculate and miraculous means, Tonantzín, or Little Mother, was the patronness of childbirth. In Mesoamerican culture, the earth was both mother and tomb, the giver of life and the receiver of human remains as they decomposed to rejoin the Life Force. Hence, the goddess was also the one to decide the length of life given to a person. As a primary force in human life, she had a devout following.

A Vision Transforms a People and Their Culture

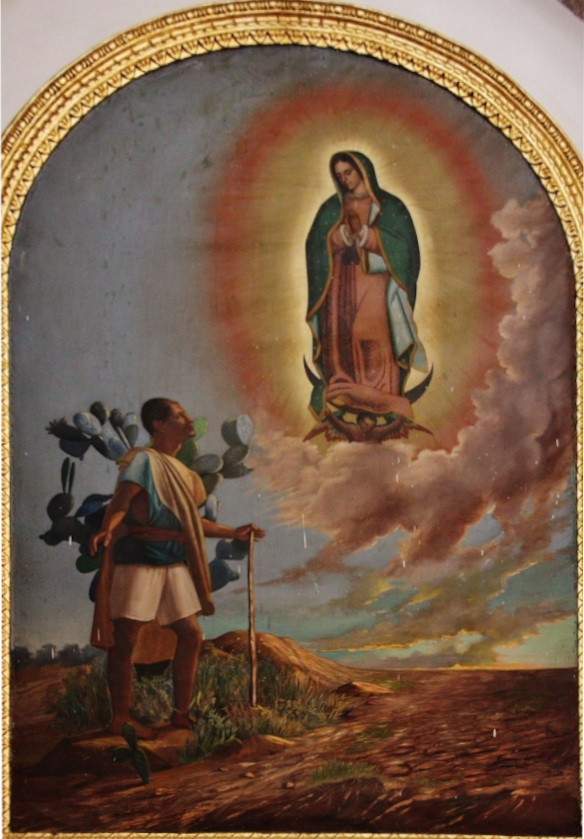

According to tradition, on a Saturday, December 9, 1531, ten years after the fall of Tenochtitlán, Juan Diego, a Náhuatl peasant who had been baptized as a Roman Catholic Christian, was passing by the hill of Tepeyac headed toward the causeway to get to the Franciscan mission at Tlatelolco for religious instruction and to perform various religious duties. He was stopped by the appearance of a young, morena, brown-skinned, woman who addressed him in Nahuatl, his native language. She was clearly one of his own, indigeous people.

|

| From Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Guanajuato, Photo by By Enrique López-Tamayo Biosca, Wikimedia |

She identified herself as Mary, the ever-virgin Mother of God, and instructed him to request that the bishop erect a chapel in her honor at that spot, so she might relieve the distress of all those who call on her in their need.

Juan Diego went into the Center of Mexico City, and reported his vision to the bishop, Fray Juan Zumárraga, who told him to come back another day, after he had had time to reflect on what he had been told.

Returning to Tepeyac, Juan Diego encountered the Virgin for a second time and announced the failure of his mission. Feeling himself to be merely "a backside, a tail, a wing, a man of no importance," Juan Diego suggested that she would do better to recruit someone of greater standing. But she insisted that it was he whom she wanted for the task. Juan Diego agreed to return to the bishop to repeat his request.

On the morning of Sunday, December 10, he returned to the bishop, who asked for a sign to prove that the apparition was truly one from heaven. Juan Diego returned immediately to Tepeyac. Encountering the Virgin, he reported the bishop's request for a sign; she agreed to provide one the following day.

On the morning of Sunday, December 10, he returned to the bishop, who asked for a sign to prove that the apparition was truly one from heaven. Juan Diego returned immediately to Tepeyac. Encountering the Virgin, he reported the bishop's request for a sign; she agreed to provide one the following day.

However, during that night, Juan Diego's uncle, Juan Bernardino, fell seriously ill and Juan Diego was obliged to attend to him. In the very early hours of Tuesday, December 12, Juan Bernardino's condition having deteriorated overnight, Juan Diego set out for Tlatelolco to summon a priest to hear Juan Bernardino's confession and administer the Last Rites to him. In order to avoid being delayed by the Virgin and embarrassed at having failed to meet her on Monday as agreed, Juan Diego chose to go around the opposite side of the hill.

|

| From Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Guanajuato, Photo by By Enrique López-Tamayo Biosca, Wikimedia |

But once again the Virgin intercepted him and asked where he was going. Juan Diego explained what had happened. The Virgin gently chided him for not having turned to her for help. In the words which have become the most famous phrase of the Guadalupe event—now inscribed over the main entrance to the Basilica of Guadalupe—she asked: "¿No estoy yo aquí que soy tu madre?" (Am I not here, I who am your mother?).

She assured him that Juan Bernardino had now recovered, and she instructed him to climb the hill and collect flowers growing there.

She assured him that Juan Bernardino had now recovered, and she instructed him to climb the hill and collect flowers growing there.

|

| From Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Guanajuato, Photo by By Enrique López-Tamayo Biosca, Wikimedia |

Obeying her, Juan Diego found an abundance of flowers unseasonably in bloom on the rocky outcrop where only cactus and scrub normally grew. Using his open mantle as a sack (with the ends still tied around his neck), he returned to the Virgin; she re-arranged the flowers and told him to take them to the bishop.

|

| From Shrine of Our Lady of Guadalupe, Guanajuato, Photo by By Enrique López-Tamayo Biosca, Wikimedia |

On gaining admission to the bishop in Mexico City later that day, Juan Diego opened his mantle, the flowers poured to the floor, and the bishop saw they had left on the mantle an imprint of the Virgin's image, which he immediately venerated.

The next day, December 13, Juan Diego found his uncle fully recovered, as the Virgin had assured him, and Juan Bernardino recounted that he, too, had seen her at his bedside; that she had instructed him to inform the bishop of this apparition and of his miraculous cure; and that she had told him she desired to be known under the title of Guadalupe. The bishop kept Juan Diego's mantle first in his private chapel, then in the cathedral on public display where it attracted great attention.

On December 26, 1531, a procession took the miraculous image back to Tepeyac, where it was installed in a small, hastily erected chapel.

Virgin of Guadalupe, Mother of All Mexicans

The reported appearance of the Virgin of Guadalupe to the recently-baptized Náhuatl peasant Juan Diego—and its combined acceptance by indigenous converts and the Catholic clergy—became the single most powerful unifying factor between the two peoples and their cultures. The conquered indigenous people identified the dark-skinned Virgin who spoke in Náhuatl with the mother goddess Tonantzín and celebrated her with indigenous-tinged rites within the framework of the Catholic Church's veneration of the Mother of the Son of God.

The Virgin of Guadalupe was also embraced by the Spanish criollos, pure-blooded Spanish born in Nueva España, rather than in Spain. The Virgin´s personal appearance on Mexican soil was seen as establishing a sacred relationship between their actual homeland and their cultural homeland, Spain. Mestizos, those with mixed indigenous and Spanish blood, who were essentially outcasts from both cultures, found in the Virgin not just the recognition, but the very embodiment and, thus, sanctification and reconciliation of their conflicted heritage.

The Basílica's official web site posts the following, remarkable statement:

"The people present the Virgin to their children as the mother of the Creator and Protector of the entire universe, who comes to the people because she wants to embrace them all—Indian and Spanish—with the same mother's love. The miraculous image imprinted on the sisal—a plant whose strong fibers were used by indigenous weavers to make tilmas (cloaks)—signaled the dawn of a new world, which was the Sixth Sun awaited by the Mexicas (Aztecs)."The Virgin had adopted the Mexican people, el pueblo, as her own; in turn, el pueblo—indigena, mestizo, criollo—adopted her as the Mother of Mexico. All of Mexico, el pueblo mexicano, still respects her. Many still adore her.

Six Churches of the Basilica Complex

Tradition says that in response to the request of the Virgin to build her a chapel at the foot of Tepeyac Hill, in 1536, Bishop Fray Juan Zumárraga replaced an original temporary shrine with a church, This was replaced in 1622 by a larger church, which, in turn was replaced by a third at the beginning of the 18th century which still stands and is known as the Old Basilica.

Meanwhile, four other churches and chapels were erected around the base and atop the small hill. Most recently, in the 1970s, as the Old Basilica was both badly damaged by sinking into poor subsoil and earthquakes and too small to accommodate the faithful for the December 12 Fiesta of the Virgin of Guadalupe, a new Basilica was built.

Here we amble around the five churches:

|

| Starting at bottom center, with the Antigua Basilica (yellow dome), going counter-clockwise, the churches are: Parroquia Capuchinas, Parroquia de los Indios, Capilla del Pocito, and Capilla del Cerrito The new Basilica is bottom, left. |

|

| Old Basilica, seen from entrance to Basilica grounds |

Antigua Basilica: The Old Basilica stands on the site of the first church, built around 1536. According to tradition, its construction was ordered by Bishop Fray Juan Zumárraga to comply with the Virgin's command. In 1622 the original church was replaced by a second structure that was, in turn, replaced between 1695 and 1709 with this Baroque-style structure, which remained in use until 1974. But this building lies, in part, over the old lake bed; consequently, there was considerable structural damage as the old lake bed continued to settle. The damage was such that a new Basilica had to be built. The old one then subsequently underwent extensive repair.

|

Dome of the Antigua Basílica,

with image of the Virgin of Guadalupe, surrounded by angels |

|

| Parochial Church of the Capuchins, a Franciscan offshoot. Built in 1797 and intended to serve parish residents. The interior is very simple. |

|

| Church of the Indians (It now has a modern interior and roof) |

|

| Chapel of the Little Well site of a spring, believed to be miraculous. |

Capilla del Pocito. Chapel of the Little Well, considered to be the exact place where the Virgin of Guadalupe appeared for the first time and spoke with Juan Diego.

|

| With its circular shape and mudejar (Moorish) dome, this one's my favorite |

|

Chapel was built in 1777

|

|

| Interior of Chapel of the Little Well |

|

| Baroque Vision of Heaven, full of Joyous Cherubs |

From the Chapel of the Little Well, a stairway leads upward, through a beautifully landscaped garden, to the top of Tepeyac Hill.

Along the way, you pass a reminder of the indigenous foundations of Mexico:

|

| Feathered Serpents, Quetzalcóatl, copied from the Temple of the Feathered Serpent, Teotihuacan, some miles north |

|

| Chapel of the Little Hill, In 1660, a small chapel was built here to commemorate the place where Juan Diego gathered the roses. This chapel was built at the beginning of the 18th century. |

|

| Inside, a wonderful mosaic of angels |

|

| On the way down, a view of the modern City. The wide boulevard follows the path of the original causeway across Lake Texcoco. |

|

| Modern Basilica, built in the 1970s, an amphitheater seating 10,000 people and housing the original image of the Virgin |

|

| "Thanks, Dear Little Virgin, for one more year." |

Other Posts in Series on Mexico City's Original Indigenous Villages:

- Landmarks of the Spiritual Conquest

- Centro's Four Indigenous Quarters - Introduction

- The Franciscans - Where It All Began

- Centro's Four Original Indigenous Quarters: San Juan Moyotla

- Centro's Four Indigenous Quarters: San Pablo Teopan-Zoquipan - Part I

- Centro's Four Indigenous Quarters: San Pablo Teopan-Zoquipan Part II - Southern Gateway

- Centro's Four Indigenous Quarters: San Pablo Teopan-Zoquipan, Part III - La Merced

- Centro's Four Indigenous Quarters: Santa María Cuepopan - Battleground and Sacred Ground

- Centro's Four Indigenous Quarters: San Sebastian Atzacoalco—Martyrs, Death, Community and Hope