An Erstwhile Puritan Confronts the Baroque

We have to admit upfront that we find it very hard to relate to, let alone appreciate Baroque art, especially Catholic Baroque visual art. (We love Bach, Vivaldi and all their musical cohort.) The intense religious symbology and overwhelming detail of the visual expressions, especially when covered in gold gilding, is off-putting to one raised as a Protestant with New England Puritan roots.

But in Mexico it is difficult to avoid the art of the Baroque epoch. It is the art of the height of the Spanish Empire and its realization in Nueva España.

So What Is Baroque?

The Wikipedia article on Baroque Art gives us a good introdution to its style and purposes.

We have to admit upfront that we find it very hard to relate to, let alone appreciate Baroque art, especially Catholic Baroque visual art. (We love Bach, Vivaldi and all their musical cohort.) The intense religious symbology and overwhelming detail of the visual expressions, especially when covered in gold gilding, is off-putting to one raised as a Protestant with New England Puritan roots.

But in Mexico it is difficult to avoid the art of the Baroque epoch. It is the art of the height of the Spanish Empire and its realization in Nueva España.

So What Is Baroque?

The Wikipedia article on Baroque Art gives us a good introdution to its style and purposes.

The Baroque is a period of artistic style that used exaggerated motion and clear, easily interpreted detail to produce drama, tension, exuberance, and grandeur in sculpture, painting, architecture, literature, dance, theater, and music. The style began around 1600 in Rome, Italy, and spread to most of Europe.

The popularity and success of the Baroque style was encouraged by the Catholic Church, which had decided in the Council of Trent (1545 to 1563) [in which Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, who was King Charles I of Spain, played a prominent role], that in response to the Protestant Reformation, the arts should communicate religious themes in a direct manner, seeking to elicit emotional involvement.

The aristocracy also saw the dramatic style of Baroque architecture and art as a means of impressing visitors and expressing triumph, power and control. Baroque palaces are built around grand courtyards, staircases and reception rooms of sequentially increasing opulence.

A good example of the Baroque is Bernini's St. Theresa in Ecstasy (1650). He aimed to portray religious experience as an intensely physical one. Theresa described her bodily reaction to spiritual enlightenment in a language of ecstasy used by many mystics.

|

| Theresa in Ecstasy Wikipedia |

Grandeur, Exuberance and Drama

La Grandeza

The analysis strikes us as going to the heart of Mexican architecture and art across its history, not just that of the Baroque period. We have written about grandeur, in Spanish, grandeza, as an essential characteristic of Mexican architecture and art from its Mesoamerican, indigenous beginnings through the Spanish Conquest and Colonial period to 19th century expressions of the Porfiriato to post-Revolutionary murals and later 20th century architecture, such as in University City.

|

| Teotihuacán, City of the Gods, "Avenue of the Dead," looking toward Pyramid of the Moon. |

|

| The Palace, first of Cortés, then the Spanish Viceroy, today the Mexican government. |

|

| Metropolitan Cathedral The facade is post-Baroque Neo-classic but with Baroque touches, such as the spiral "solomonic" columns above the two side doors. |

|

| Mural of "Progress" on ceiling of Reception Hall of former Secretariat of Communications, now National Museum of Art. Built during 30-year presidency of Porfirio Díaz, aka the Porfiriato |

|

| Central Library of National Autonomous University University City, Coyoacán Mural by Juan O´Gorman is a mosaic in natural stones. Covering the Library's four sides, it is the world's largest outdoor mural. |

Exuberance

The Wikipedia author uses the word exuberance for the lavishness, the profuseness of imagery and decoration characteristic of Baroque art. Again, that lavishness is present from the beginnings of Mexican art up to the present.

|

| Goddess of Tenochtitlán Mural in National Museum of Anthropology and History |

|

| Bird Jaguar IV, center, with his father, Itzamnaaj B'alam II and grandfather, Yaxun B'alam III, Ahaus, Lords of Maya kingdom of Yaxchilán |

|

| Baroque reredos of Church of San Ángel, Colonia San Ángel, Delegación Álvaro Obregón |

|

| Tianguis, Street Market Mural in Abelardo Rodríguez Market Artist unknown, 1930s. |

|

| Giant papier maché alebrije, fantastic creature in the Zócalo, Day of the Dead, November 1-2 |

|

| Fiesta of El Señor de la Misericordia Lord of Compassion, Pueblo de los Tres Santos Reyes, Pueblo of the Three Saintly Kings, Coyoacán |

Drama

Drama is probably the central theme of Mexican art from its Mesoamerican roots to its modern expressions. From its indigenous beginnings, the Mexican worldview has been a dramatic one, full of protagonists and antagonists, heroes and villains, the forces of good versus the forces of evil, entangled in a lucha, a struggle for victory one over the other.

The Christian drama brought by the Spanish fit right in: God versus Satan, Heaven versus Hell, Christ versus Sin and Death. In the great human and divine drama, the Lord is crucified, dies, is buried and rises again.

|

| Death "Frieze of the Dream Lords," Maya, Toniná, Chiapas |

|

| Sarcophagus of Pakal Kínich Janaab I (Great Sun Shield), Maya Lord of Palenque (reigned 615 - 683 AD). Pakal lies on top of a god of the underworld. A cruciform world tree (cosmic axis) rises from him carrying his spirit to a bird, the supreme sky god, Itzamnaaj. |

|

| Aztec Stone of the Five Suns National Museum of Anthropology and History Photo: Ann Kingman Gomes |

|

| Virgin Mary (left) pleads with Heavenly Christ (in red), seated next to God, the Father, for "Release of the Souls in Purgatory" (including a Pope (lower right) and a Cardinal (lower left) Baroque period painting in the Metropolitan Cathedral |

|

March of Humanity Toward the Democratic, Bourgeois Revolution

Top: Primitive Man, Pregnant Proletariat Woman, March of the Mothers, with their burdens Bottom: The Embrace and Mixing of Races, Lynched Black Man, Crow Man of the Pimas and Yaquis (indigenous peoples) |

|

| The peoples don't protect (their) memory. Ariosto Otero Reyes, 1997 Xola ('Shola') Metro station, Line 2 |

Ecstasy and Awe

Ecstasy: Communion with the Divine

The word ecstasy is Greek in origin, ek-stasis, and means to stand outside (one's self); stasis has the same Indo-European root, sta, as the Spanish verb estar, to be in some place, and the English state, stance or station. We usually think of ecstasy as an experience akin to that of St. Theresa, an emotional experience so heightened in intensity as to carry a person, at least for some moments, totally beyond themselves, beyond their normal physical, mental and emotional experience.

Ecstasy, at its most intense, carries one to communion with the Divine (from Indo-European deiw, meaning "to shine"; hence, "sky," "heaven"), that is, with Ultimate Reality.

|

| The Assumption of Mary into Heaven, to become "Queen of Heaven." An ecstatic event, if ever there was one. Heavenly cherubs raise her from the human world below. Sculpture over main door of The Metropolitan Cathedral whose full name is Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Most Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven |

Ecstasy as intense as that of the mystics like St. Theresa, or the shamans of earlier cultures (who had visions in which their spirits left their bodies to visit the world of the supernatural), is hard to imagine for most of us mortals. But "standing outside of one's self" in less intense ways is a common experience. We all seek ways to "stand outside" our daily routines, the everyday times and places of our lives, our existential reality. Sports, games, dance, music, literature, theater, painting, parties, holidays, vacations—all forms of play—as well as alcohol, drugs and, of course, sex take us outside ourselves. All are forms of ecstasy, in greater or lesser intensity.

Yet this ecstasy, in all its forms and levels of intensity, can never totally take us out of our historical and cultural context, our imaginario, our communally shared worldview. We play the games of our culture. Our music and all our arts are of a particular time and place, an epoch. And what is more typical of a culture than how it celebrates or relaxes? Each culture has its favorite form of alcohol, be it beer made from barley, corn or rice; wine, brandy or whiskey. Drugs and sex? Well, they are universal, but even they are culturally shaped.

So is our religion: our images of God and the practices of our worship, our efforts to commune with Ultimate Reality. In the Catholic Christian world, ecstasy, communion with the Divine, is mundanely attained in the Mass, when a wafer of grain consumed by the faithful miraculously becomes the Body of Christ. However, the ultimate ecstasy is achieved by entrance into heaven after death. Baroque religious art focuses on this final realization of eternal ecstasy.

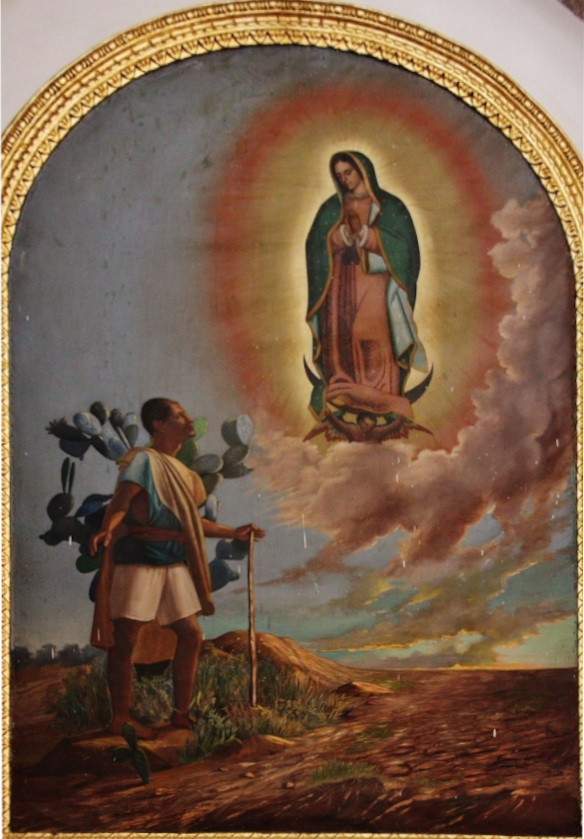

|

| Virgin Mary, Queen of Heaven, in her manifestation as Our Lady of Guadalupe, on dome of Old Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe. Gold represents the shining, resplendent Divine Presence; Communion with that Presence is the ultimate goal of ecstasy. |

|

| Heaven full of cherubs, innocent infants. On the dome of the Chapel of the Little Well Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe |

Awe

Awe isn't mentioned by the Wikipedia author, but it is implied in his/her analysis of Baroque art, with its grandeur and desire to impress. Awe is a powerful feeling of reverence, fear or wonder in response to an encounter with something experienced as greater or more important than our mundane concerns, something truly grand, something essentially sacred and holy (from the Indo-European roots, sak: to set aside from everyday use, and kailo: whole, healthy, wholesome). Clearly Baroque religious architecture and art was intended to evoke awe in the presence of the sacred, the holy, the divine.

|

| Interior of Metropolitan Cathedral |

|

| Worship Side chapel Metropolitan Cathedral |

Baroque Art as Expressions of Ecstasy Evoking Awe

It is with this perspective on Baroque art as focused on grandeur, exhuberance, and drama, and its religious expresssions as portraying ecstasy and seeking to induce awe, that we can approach the architecture and art of the Baroque churches and palaces of Mexico City as shaped by the imaginario of their time and culture: Spanish Catholic Colonial Mexico of the 17th and 18th centuries.

|

| "Ecstasy" A contemporary exhibit of portraits of female Catholic saints and nuns as Brides of Christ, following very much the path of St. Theresa. (Unfortunately, it was closed when we arrived in late June to explore the Ex-Convento Culhuacán in Delegación Iztapalapa) |

Spanish Baroque: Churrigueresque

Spanish Baroque is marked by extremely expressive, florid decorative detailing, normally found above the entrance on a building's main facade. It is also called Churrigueresque, from the name of architect and sculptor José Benito de Churriguera (1665–1725), who championed it. Born in Madrid, De Churriguera worked primarily in Madrid and Salamanca (Wikipedia).

It is this Churrigueresque Baroque that was brought to Nueva España and its capital, la Ciudad de México. There are multiple examples of it in Centro Histórico.

|

| El Sagrario Metropolitano, The Metropolitan Tabernacle, Designed by Spanish architect Lorenzo Rodríguez Built between 1749-60 |

El Sagrario Metropolitano, the Metropolitan Tabernacle is a building attached to the east side of the Cathedral. It housed the archives and vestments of the archbishop. It now functions as a place to receive baptism and the Eucharist and to register parishioners.

|

Temple of San Francisco,

Baroque facade of Balvanera Chapel

built in 1766,

also by Spanish architect Lorenzo Rodríguez

Entrance on Madero Street

|

|

| Iglesia de la Santésima Trinidad, Holy Trinity Church Centro Histórico, East. Probably also by Spanish architect Lorenzo Rodríguez |

Santésima Trinidad, Holy Trinity Church sits a few blocks east of the Cathedral. The current church was completed in the 1750s, replacing an earlier church built at the beginning of the 1600s. It was likely also designed by Lorenzo Rodríguez.

Inside Baroque Temples: Roman Empire with Elaborate Decoration

Crossing the thesholds of a Baroque church is to enter a world that has its roots in the Roman Empire, and the grandeur of its basilicas. The Roman basilica was originally a public building where rulers held court, but the basilica also served other official and public functions. To a large extent, these were the town halls of ancient Roman life. The basilica was centrally located in every Roman town, usually adjacent to the main forum (much as the Spanish, and then Mexican, ayuntamiento, municipal hall is).

These buildings were rectangular and often had a central nave and two side aisles, usually with a slightly raised platform and an apse at each of the two ends, adorned with a statue perhaps of the emperor, while the entrances were from the long sides.

Churches of the Christian faith, once it became the official religion under Emperor Constantine (306-337 CE), adopted the same basic plan—thereby also appropriating a representation of the grandeur of the Roman Empire. Later, the term came to refer specifically to a large and important Roman Catholic church that has been given special ceremonial rights by the Pope. The most famous of these is, of course, St. Peter's Basilica in the Vatican in Rome. Wikipedia

In an earlier post on our pursuit to discover the origins of the spiral "Solomonic" columns that appear on Mexico City houses built in the 1920s and 30s (California Colonial: From Emperor Constantine to Mexico Via Spanish Baroque), we saw how the Baroque style of architecture, with its ornate interior, as well as exterior, decoration began with the building of the "new" St. Peter´s Basilica in the 17th century.

Metropolitan Cathedral of Mexico City

In Mexico City, the preeminent basilica and prime example of Baroque religious architecture and art is the Metropolitan Cathedral. So it is that threshold we cross to encounter the Baroque up close. (Wikipedia has an excellent extensive article on the history and components of the Cathedral.)

|

| Baroque "Solomonic" columns above one of the side entrances to the Metropolitan Cathedral. |

|

| Side aisle of Metropolitan Cathedral Classic Roman basilica design |

The Cathedral is designed according to the Roman framework of a rectangle divided into a central aisle and two side aisles. It is within this classic framework that a grand, exuberant and dramatic Baroque elaboration has been carried out.

Entering the Cathedral, we are greeted by the Altar of Forgiveness.

|

| Altar of Forgiveness Designed by Spanish architect Jerónimo Balbás early 18th century, Damaged by a fire in 1967 and restored. |

|

| Golden Sun, symbol of the Glory or Resplendence of the Divine (Shining) Presence atop the Altar of Forgiveness |

Along each side aisle of the Cathedral are seven ornate Baroque chapels. Most are cordoned off by floor to ceiling wooden grills and open only for specific occasions. This also makes them difficult to photograph (which is also formally prohibited).

At the far north end, the apse of the sancturary, is the Altar of the Kings, so-named because statues of saintly royalty are placed on its walls. Because of its size and depth, it is known as the "Golden Cave".

|

| Altar of the Kings work of Jerónimo Balbás, begun in 1718, carved in cedar; guilding by Francico Martínez, finished in 1737. |

Hermenegild, a Visigoth king and martyr, Holy Roman Emperor Henry II,

Edward the Confessor and Casimir of Poland

As we said in the introduction, we tend to feel overwhelmed by Baroque ornateness, put off rather than experiencing anything close to ecstasy or awe. But in coming upon the four Saintly Kings, we have a different experience. Up close, they are very human figures. Their faces are kind, even sad. We feel we would like to get to know them better.

The Appeal Rests in the Details

So we seek out more details:

|

| Figure holding up the choir screen |

|

| Saint and cherub atop Altar of Forgiveness |

|

| Angel atop Altar of Forgiveness |

|

| A worried St. Peter on door of El Sagrario |

The Lord Jehovah, (in the style of Zeus or Jupiter, both meaning "of the sky") on door of El Sagrario |

Puritan, Humanist Ecstasy and Awe

We remain a "Puritan Protestant", and even more so, a humanist of the Enlightenment, so the grandeur, lavishness and drama of Baroque art continue to be not to our taste. For us, the Divine splendor resides in each creature of the Creation. And so we do feel something of ecstasy and awe when we encounter these saintly figures. They are dramatic, yet simple, direct, human. Vulnerable. And the cherubs have the delightfulness and, of course, the vulnerability of early childhood.

Old saints, bearded gods and charming infants—the two ends of the human life cycle—to represent closeness to the Holy, an ecstatic encounter with the Divine. It may seem to be a curious combination, but we'll revere our meeting.

See also:

- Grandeza Mexicana: Grandeur of Mexico City

- The Zócalo, Symbolic Heart of Mexico City and Mexico

- Centro: Making a Living Amidst Faded Grandeur

- The Spiritual Conquest: The Franciscans - Where It All Began

- The Grandeza of Porfirio Díaz

- Monument to the Revolution: Heroes and Enemies Together in Death

- Mexican Muralists - Part I: Bellas Artes

- Mexican Muralist at the National Autonomous University

- Mexican Muralists: David Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum

- California Colonial: From Emperor Constantine to Mexico via Spanish Baroque