In the early 1920s, after the Mexican Revolution, Siqueiros took part with Rivera and Orozco in creating the first works of the Mexican Mural Movement in the National Preparatory School (former College of San Ildefonso). However, because of changes in the political environment, he did not finish the mural he began there and was not to leave his own visible artistic mark on the city until some twenty years later in the 1940's. (Note: some time after writing this post, we were able to see Siqueiros's first, partial work, See: David Siqueiros. Part III)

| David Alfaro Siqueiros |

Beginning with his art school studies in the mid-1910s and continuting through three-plus turbulent decades of Revolutions (Mexican and Russian), the Great Depression and two World Wars, until the end of his life in the 1970s, Siqueiros immersed himself in a personal political, cultural and geographic quest to discover and create for the modern world what he envisoned to be an art that was truly contemporary not only in its aesthetic, but also in its materials and techniques—an art, moreover, that communicated on grand scales in public spaces the core political issues of the epoch.

To tell the convoluted tale of his spiritual, political and artistic journey, we have written the page David Siqueiros: Twentieth Century Odysseus. In this post, we explore the art that he created in public spaces in Mexico City.

Palacio de Bellas Artes

In 1944, after passing through the Mexican Revolution, Paris, Italy, Guadalajara, Los Angeles, Uruguay, Argentina, Moscow, New York, the Spanish Civil War, an assassination attempt against Leon Trotsky and several stays in Mexico City's Lecumberri Prison, Siqueiros was back in Mexico City, out of prison and painting. The National Institute of Fine Arts commissioned him to create murals for Bellas Artes. Creating their own murals in the 1930s, Rivera and Orozco had preceded Siqueiros there by ten years.

Siqueiros' murals in Bellas Artes are direct, forceful examples of the sculptural, almost three- dimensional style he had developed over the years in smaller works. By foreshortening the subjects, the muralist makes them thrust forward, so they appear almost to attack the viewer. Their theme isn't the Mexican Revolution. It is World War II and the battle against Fascism which was at its height.

To tell the convoluted tale of his spiritual, political and artistic journey, we have written the page David Siqueiros: Twentieth Century Odysseus. In this post, we explore the art that he created in public spaces in Mexico City.

Palacio de Bellas Artes

In 1944, after passing through the Mexican Revolution, Paris, Italy, Guadalajara, Los Angeles, Uruguay, Argentina, Moscow, New York, the Spanish Civil War, an assassination attempt against Leon Trotsky and several stays in Mexico City's Lecumberri Prison, Siqueiros was back in Mexico City, out of prison and painting. The National Institute of Fine Arts commissioned him to create murals for Bellas Artes. Creating their own murals in the 1930s, Rivera and Orozco had preceded Siqueiros there by ten years.

Siqueiros' murals in Bellas Artes are direct, forceful examples of the sculptural, almost three- dimensional style he had developed over the years in smaller works. By foreshortening the subjects, the muralist makes them thrust forward, so they appear almost to attack the viewer. Their theme isn't the Mexican Revolution. It is World War II and the battle against Fascism which was at its height.

|

| Victim of Fascism Bellas Artes, 1944 The near-naked figure could as well be a slave from Roman times. |

|

| The New Democracy Emerging from the volcano's fire, Liberty breaks her bonds. She wears the red French Liberty Cap, a symbol also used by Orozco. "New Democracy" possibly refers to Mao Zedong's concept that Chinese Communism would emerge directly from the working, peasant, small business and large capitalists, skipping the Marxist stage of imperial capitalism and colonialism. |

Six years late, in 1950, Siqueiros was invited back to place murals on the opposite side of the second balcony. Instead of a contemporary story of oppression, here he portrayed an historical, Mexican one: the Spanish Conquest of the Aztecs.

To execute these murals, Siqueiros used pryoxilin, a modern synthetic paint that enables surfaces to be built up, hence creating a sculpted effect. Rivera and Orozoco worked in the ancient technique of fresco, paint on wet plaster. Siqueiros criticized them for being old-fashioned.

University City

The campus was to be a major embodiment of Mexico's drive to become a modern nation and, by the same token, a physical, visible expression of national pride and identity. Siqueiros and other Mexican artists were invited to create outdoor murals on the buildings to communicate those messages. He was assigned the Rectory, the main administration building at the center of the huge campus.

The mural is entitled The People to the University, The University to the People: For a National Neohumanist Culture of Universal Depth. Here Siqueiros carried the three-dimensional appearance of his earlier work into true, sculptural three dimensions. This technique was to be carried to its fullest expression in his final masterwork, the Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum. The universal humanistic theme of education—in place of a specifically revolutionary theme—also foreshadows that later work.

National Museum of History, Chapúltepec Castle

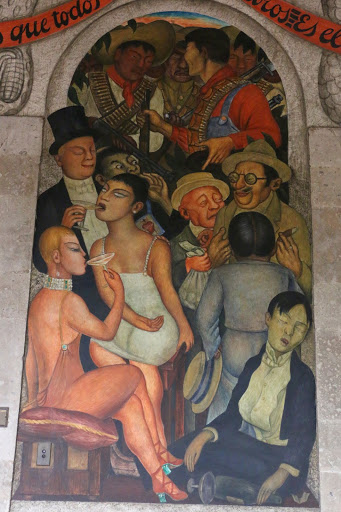

In 1957, Siqueiros was commissioned by the government to create a mural for the National Museum of History in Chapúltepec Castle. Titled From the Dictatorship of Porfirio Díaz to the Revolution, Del porfirismo a la Revolución, this was his biggest mural yet, and the only one directly portraying the Revolution.

|

| Del porfirismo a la Revolución, from the Porfiriato to the Revolution. Díaz is surrounded by his scientificos, technocratic bureaucrats, and female tiples (sopranos), singer-entertainers of the day. His left foot rests atop the Constitution of 1857. |

|

| During the Cananea Consolidated Copper Company strike in Sonora, in 1906, rural police and hired Arizona rangers prepare to repress miners and strike leaders. Rafael Izabal, governor of Sonora, accompanied by the president of the U.S.-owned company, William C. Green, tries to seize the Mexican flag from Esteban Baca Calderón. Workers carry a victim of the repression. Other leaders of the Revolution appear, including Francisco Ibarra and Manuel M. Diéguez (moustache), under whom Siqueiros served during the Revolution. |

|

| The People in Arms include (second and third rows, from left) Francisco I. Madero (bald), Venustiano Carranza (full beard), Eufemio and Emiliano Zapata (red sombrero), Álvaro Obregón (moustache, cowboy hat) and Plutarco Calles (moustache, large sombrero). The country in flames is symbolized by the woman (red dress) on the right. |

|

| The Revolutionary, abruptly reining in his horse, symbolizes the end of the armed struggle. One feels the horse's momentum is going to carry it beyond the mural's frame. |

|

| Row of Corpses symbolizes Revolution's cost in terms of human lives lost. The first figure is Leopoldo Arenal, father of Siqueiros' third wife, Angélica, who was killed in 1913. |

While this sequential mural starts out with a clear, revolutionary political position, it ends with a brutal realism that reminds us of Orozco's images in San Ildefonso.

Obra Interrupted

Siqueiros's work on the mural was interrupted by his political activities. In 1960 he was again arrested for openly criticizing Adolfo López Mateos, then President of Mexico, and for leading protests against the arrests of striking workers and teachers. He was imprisoned, yet another time, in Palacio de Lecumberri. While there, he continued to paint.

|

| Siqueiros painted this panel for a theater performance put on by prisoners in Palacio de Lecumberri Prison. On display in Palacio de Lecumberri, now the National Archives. |

During that imprisonment, he also made numerous sketches for a proposed mural project in the Hotel Casino de la Selva in Cuernavaca, Morelos. In the spring of 1964, Siqueiros was finally released and immediately resumed work on his suspended murals in Chapultepec Castle, which he completed in 1966.

Climactic Chapter of Revolutionary Art

Next we move to an aging David Siqueiros—militant Communist, who had fought in the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, who had attempted to assassinate Leon Trotsky—to explore his final, grand project of the late 1960s.

Slated for a luxury resort hotel in Cuernavaca being built by a wealthy entrepreneur (quintessential capitalist who likely would have been quite comfortable in the pre-Revolutionary Porfiriato), the project was to end up being something even grander, more complex, and also quite challenging for the viewer to comprehend, very much like the artist himself. And it was to end up being realized in Mexico City as the Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum, which is subject of our next post.

See our other posts on the Mexican Revolution and Mexican Muralists:

For the story of the Mexican Revolution, see: Mexican Revolution: Its Protagonists and Antagonists

Climactic Chapter of Revolutionary Art

Next we move to an aging David Siqueiros—militant Communist, who had fought in the Mexican Revolution and the Spanish Civil War, who had attempted to assassinate Leon Trotsky—to explore his final, grand project of the late 1960s.

Slated for a luxury resort hotel in Cuernavaca being built by a wealthy entrepreneur (quintessential capitalist who likely would have been quite comfortable in the pre-Revolutionary Porfiriato), the project was to end up being something even grander, more complex, and also quite challenging for the viewer to comprehend, very much like the artist himself. And it was to end up being realized in Mexico City as the Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum, which is subject of our next post.

See our other posts on the Mexican Revolution and Mexican Muralists:

Part I: Bellas Artes

Part II: The Academy of San Carlos and Dr. Atl

Part III: Secretariat of Education, José Vasconcelos and Diego Rivera

Part IV: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Vision of Mexican Traditions

Part V: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Ballad of the Revolution

Part VI: Diego Rivera at the College of San Ildefonso

Part VII: José Clemente Orozco Comes to San Ildefonso

Part VIII: College of San Ildefonso and José Clemente Orozco - Continued

Part X: David Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum

Part XI: The Abelardo Rodríguez MarketSee also our short biography: David Siqueiros: Twentieth Century Odysseus

For the story of the Mexican Revolution, see: Mexican Revolution: Its Protagonists and Antagonists