Curiously, it begins not at the top of the stairs, but in a corner of the Patio of Labor.

|

| Cantando El Corrido de la Revolución Singing the Ballad of the Revolution |

A balladeer, accompanied by a guitarist, shares with el pueblo, the common or ordinary people, the story of the Revolution, or better, a vision of the Revolution, its heroes and its villains. The words of their ballad are inscribed on a red banner that runs above the series of murals.

|

| Banquete de Wall Street Note the Statue of Liberty lamp The banner overhead says, "They are always thinking of their money." |

Using his style of caricature painting which we saw in his Bellas Artes murals, Rivera portrays the self-satisfied, self-centered bourgeois capitalist class, and his contempt for them.

|

| Los Sabios The Wise Ones |

Rivera's disdain extends to the apparent "thinkers" of capitalism. Why he puts a Confucius-like figure in the center remains a mystery. And here, in the background, watching and waiting, are the worker-soldiers of the Revolution and a campesino, peasant farmer, with the wheat that is the source of food for all.

|

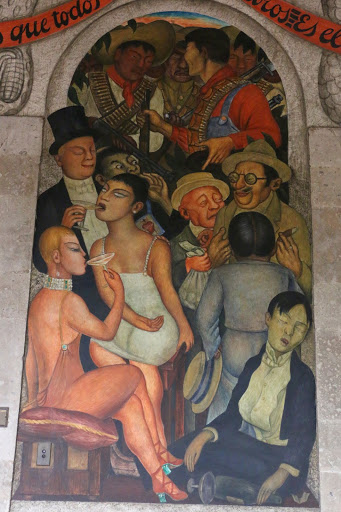

| La Orgia-La Noche de los Ricos The Orgy-The Night of the Rich |

In The Orgy, Rivera goes all out in portraying the debauchery and dissipation of the wealthy. Again, the soldiers of the imminent Revolution loom in the background.

|

| La Cena del Capitalista The Capitalist's Supper |

The Capitalist's Supper carries a message of Revolutionary justice and revenge. The family that once enjoyed banquets is left with little to eat, while the Revolutionary soldiers, the workers of the land and the factories, hold a cornucopia of the bread and fruits that are the results of their labor.

It is interesting that one soldier appears to be African and the other Chinese. When Rivera was painting these murals, in 1927 and 1928, was the very moment that the Chinese Civil War was beginning between the Chinese Communist Party, led by Mao Zedong and the Nationalists led by Chiang Kai-shek

|

| El Sueño-La Noche de los Pobres The Dream-the Night of the Poor |

Meanwhile, the poor have but one dream: to obtain work by which they can feed themselves and their children.

|

| The Union "Union is the holy force" |

The call to Revolution is a call to Unity, between worker and peasant, as we saw in The Embrace downstairs, but also between the indigenous and the urban middle class. There will be bread for all.

The Revolution Arrives

|

| Worker and farmer threw off the yoke that they suffered and burned the malignant vice of the bourgeois oppressor |

The ballad continues with the eruption of armed rebellion.

|

| El Arsenal The Arsenal Frida Kahlo, with her inimitable eyebrows, wearing the red shirt and star of Communism, distributes weapons. |

Frida Kahlo met Diego Rivera in 1927 when she came to where he was working on the murals of the Secretariat of Public Education. She was twenty and only partially recovered from a near-fatal bus accident two years earlier that was to leave her partially crippled for life. Rivera was forty. They were married two years later. In The Arsenal, Rivera places the young Kahlo at the center of his revolutionary vision.

What is portrayed is clearly not the Mexican Revolution that took place between 1910 and 1917. Kahlo was only ten at the time that ended. And there was no Communist Party in Mexico until 1919. We are seeing here Rivera's dream of a future rebellion modeled after the Revolution in Russia.

|

| Diego Rivera looks on Wearing the Red Star of Communism |

When Rivera painted this Communist Revolution, the Mexican Communist Party was outlawed. How he managed to paint such an explicit Communist message on the top floor of José Vasconcelos's Secretariat of Public Education is another mystery.

|

| En La Trinchera In the Trenches |

|

| La Lluvia The Rain Soldiers wearing capes made of plant fronds take shelter with an indigenous camepsino family |

Messages of Revolution

|

| El Que Quiere Comer Que Trabaje He Who Wants to Eat Has to Work "Lazybones: He that wants to eat has to work" Interestingly, a fine artist painter/musician is pushed to the floor by a soldier in his blue work overalls. Rivera saw the vocation of art to be serving the common people. |

|

| Garantias, Desechos del Capitalismo Rights, the Garbage of Capitalism At the top, a wealthy priest is hit with a worker's hammer as he exits his money safe, while a peasant uses his sickle to cut off the head of another capitalist. |

|

| La Muerte del Capitalista The Death of the Capítalist "Whoever wants to exploit, the misery of the past is finished" |

|

| Un Solo Frente A Single Front "...they made a single front" Note: The unifier is a "güero", a blond, light-skinned Russian Communist |

|

| La Cooperativa factories "managed in cooperatives, without bosses" |

Fruits of Revolution

|

| El Pan Nuestro Our Bread "...bread for all the naked..." and all the fruits of labor. |

|

| Alfabetización-Aprendiendo a Leer Literacy-Learning to Read |

|

| Los Frutos de la Tierra The Fruits of the Earth, including knowledge, are shared |

Coda

|

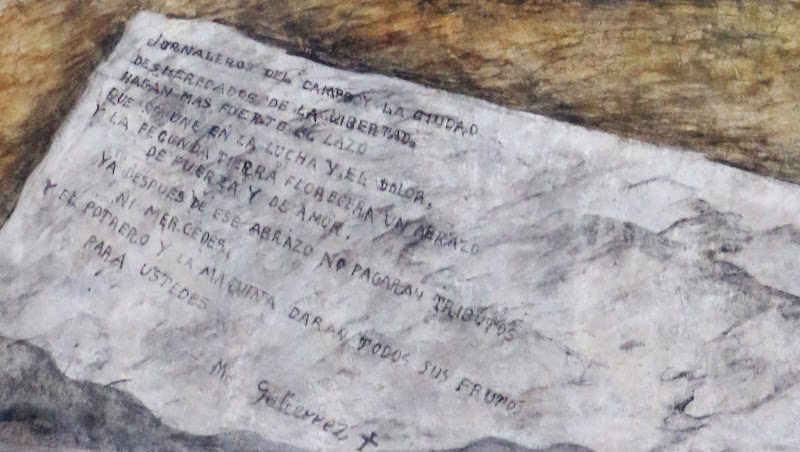

| Emiliano Zapata "In Morelos there was a very singular man." Land and Liberty |

The Ballad of the Revolution ends in the corner of the Patio of Labor, next to where its telling began. There stands Emiliano Zapata while musician-warriors sing his story:

"In Morelos there was a very singular man."We are not told the words of their ballad. As for what actually happened with Zapata, see the Mexican Revolution link below.

See more on the Mexican Revolution and Mexican Muralists:

Part I: Bellas Artes

Part II: The Academy of San Carlos and Dr. Atl

Part III: Secretariat of Education, José Vasconcelos and Diego Rivera

Part IV: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Vision of Mexican Traditions

Part VI: Diego Rivera at the College of San Ildefonso

Part VII: José Clemente Orozco Comes to San Ildefonso

Part VIII: College of San Ildefonso and José Clemente Orozco - Continued

Part IX: David Siqueiros, Painter and Revolutionary

Part X: David Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum

Part XI: The Abelardo Rodríguez MarketFor background of Mexican Revoluion, see:

Mexican Revolution: Its Protagonists and Antagonists