|

| José Clemente Orozco, by David Siqueiros, Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum, Delegación Benito Juárez, Mexico City |

Secretary of Public Education José Vasconcelos had put Rivera to work creating murals in the Secretariat of Education, so he hired artist José Clemente Orozco (1883-1949) to add more murals in the Preparatory School. Orozco was forty years old.

Born in the western state of Jalisco, his family had moved to Mexico City in 1890, when he was seven. He was enrolled in the elementary school of the Teachers College in the Centro Histórico. On his way to school, Orozco recounts in his Autobiography, he would pass the printing shop where José Guadalupe Posada (February 2, 1852 – January 20, 1913) worked as an engraver, illustrating books and newspaper stories.

|

José Guadalupe Posada, by David Siqueiros, Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum, Delegación Benito Juárez, Mexico City |

Orozco was fascinated. He felt

"impelled to cover paper with my earliest figures; this was my awakening to the art of painting."At some point while still attending elementary school, he enrolled in evening classes at the San Carlos Academy of Fine Arts. Diego Rivera, who was three years younger, also started studying at the Academy in 1896, at age 10.

In 1897, at age fourteen, Orozco's father sent him to the San Jacinto School of Agriculture, just outside the city. Completing the three-year course, in 1900 Orozco enrolled in the National Preparatory School, planning to study architecture. But his passion for painting overtook him and he left to enroll in San Carlos. His father had died, so he supported himself working as a draftsman for architects and newpapers.

In 1911, when Francisco Madero and others had overthrown Porfirio Díaz, Orozco, now twenty-eight, got work through a journalist friend as a cartoonist with an opposition newpaper. As for taking sides in the Revolution, Orozco wrote later in his Autobiography:

"I might equally well have gone to work for a government paper instead of the opposition. No artist has, or ever has had, political convictions of any sort. Those who profess to have them are not artists."He joined the student strike at the Academy, seeking to throw out the director and the Neoclassic curriculum. When Alfredo Ramos Martínez became director of the re-opened Academy and led students to paint plein air, in the open air, at a house he rented in the then rural village of Santa Anita Ixtapalapa (now part of the Mexico City borough of that name), Orozco initially went along. But he soon found the focus on French Impressionism too precious for his taste. Instead of their

"pretty landscapes with the requisite violets and Nile greens, I preferred black and the colors exiled from Impressionist palettes. I painted the pestilent shadows of closed rooms, and instead of the Indian male, drunken ladies and gentlemen."He left and rented his own studio in thc City Center.

By his own account, he took no part in the various phases of the Revolution, despite U.S. newspaper accounts to the contrary. He felt Madero's presidency was "a half revolution, sheer confusion and senseless." Huerta was

"no doubt a monster, but no different from others who fill the pages of history."After Huerta's defeat in October of 1914, the forces of Villa and Zapata on one side and Carranza on the other failed to agree on a new government at the Convention of Aguascalientes. Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata then directed their armies at Carranza's. In November, Carranza retreated to the state of Veracruz. Dr. Atl, the students' mentor at the Academy, convinced many of them to join him and Carranza. Orozco went with him to the city of Orizaba, helped set up printing presses and drew political cartoons against Villa and Zapata. And witnessed the horrors of war:

"The world was torn apart around us. Troop convoys passed through on their way to slaughter. Trains were blown up. Wretched Zapatista peasants who had fallen prisoner were summarily shot down. People grew used to killing, to the most pitiless egotism, to the glutting of sensibilities, to naked bestiality.

"In the world of politics, it was the same, war without quarter, struggle for power and wealth. Factions and subfactions were past counting; the thirst for vengeance insatiable. And underneath it all, subterranean intrigues went on between the friends of today and the enemies of tomorrow, resolved, when the time came, upon mutual extermination. Farce, drama, barbarity. Buffoons and dwarfs, trailing along after the gentleman of the noose and dagger, in conference with smiling procuresses."In 1917, after Carranza had defeated Villa and Zapata and become president, and some stability returned to Mexico, Orozco, now thirty-four, seeing no future for himself in Mexico, left for the United States. Carrying some of his rolled-up paintings with him, he was inspected by U.S. Customs Officials at the border in Laredo, Texas. They destroyed sixty of his paintings because they were seen as "immoral," even though, Orozco comments, "there were no nudes."

Orozco went on to San Francisco, where acquaintances took him in and he survived with small painting and printing jobs. He later moved on to New York City, where he loved Harlem and Coney Island.

In 1922, seeing that "the table was set for mural painting," Orozco returned to Mexico. In 1923, he was hired by José Vasconcelos to paint murals in the National Preparatory School, the former Jesuit Colegio de San Ildefonso.

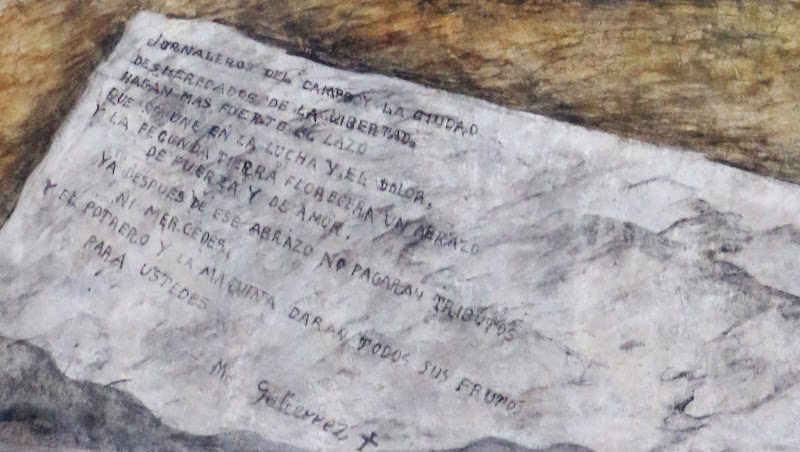

|

| Inner patio of San Ildefonso Some of Orozco's murals can be glimpsed in the passageway on the right Photo: Rebecca Brundage Clarkin |

Orozco's first painting seems to be a continuation of both the classic imagery and idealized, hopeful theme of Rivera's Creation.

|

| Maternidad Maternity |

Maternidad is an ethereal, semi-modern reworking of a Renaissance or even Baroque-style portrayal of a Madona and her child, now blond and naked, surrounded by hovering angelic figures. Striking both in its idealization and boldness, it is at the same time strange, as if from the Art Nouveau end of the 19th century rather than the third decade of the 20th. This and other murals Orozco painted in the Preparatory School at the time were strongly criticized, including by Catholics who saw them as blasphemous. Orozco responded by destroying all but this mural and quitting the job.

An Artistic Revolution in Style and Vision

At the end of 1924, Plutarco Elías Calles became president and announced several populist projects to fulfill the Revolutionary desires of peasant farmers for land and urban laborers for the workers' rights that had been incorporated into the Constitution of 1917. Orozco decided to return to San Ildefonso in 1926 and began painting again, restoring some of his destroyed murals, but now he worked in a starkly modern style, presenting a startling perspective on the events that, a decade before, had devastated the country.

Next to Maternidad he painted a series of murals on the Mexican Revolution very different from the optimistic, idealized ones Rivera was realizing nearby in the Secretariat of Education. In them, Orozco gave visual life to his autobiographical observations on the brutality and senselessness of the Revolution.

|

| La Trinchera The Trench |

The vital, velvet rich reds and warm golds of Maternidad are replaced with somber greys, tans and black and a touch of blood red in the background, the colors that he has told us he loved. We are confronted with three revolutionary soldiers falling in battle. Two topple, arms extended as if crucified, against hard, harsh rock. The third doubles over on his knees, covering his eyes from the scene. The contrast with Rivera's heroic Trinchera, in his Ballad of the Revolution, could not be more striking.

|

| Diego Rivera's En la Trinchera Secretariat of Public Education |

Further along the colonnade of the planta baja, the ground floor, we encounter a more symbolic but almost as disturbing image of the Revolution.

|

| La trinidad revolucionaria The Revolutionary Trinity |

This very non-Christian Trinity is composed of a central figure holding a rifle but blinded by the Red Cap of Liberty that had been the symbol of the French Revolution. The left-hand figure covers his eyes, similar to the third figure in La Trinchera. The right-hand figure has had his hands cut off. Behind him is a small, paradoxical slice of the azure Mexican sky.

Alongside this critical, to say the least, even sardonic and despondent view of the Revolution, Orozco places his view of the bourgeois upper-class.

|

| El banquete de los ricos Banquet of the Rich |

Here Orozco is much more in synch with Rivera's view of wealthy capitalists.

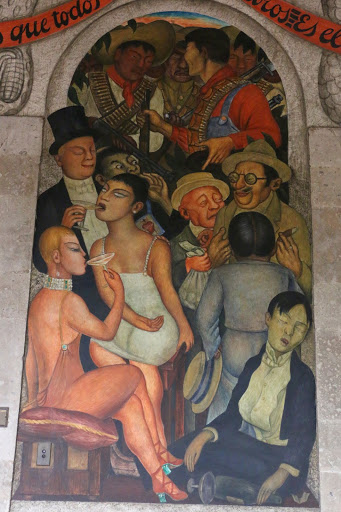

|

| La Orgia-La Noche de los Ricos The Orgy-The Night of the Rich Diego Rivera Secretariat of Education |

However, the style of Rivera's "Orgy" and the figures within it seem tame, aloof, stilted compared to Orozco's over-the-top painting style and his corpulent, drunken, contemptuous diners.

With this stark introduction to both sides of the early 20th century's economic and political divides, we start up the stairs to the two upper floors, wondering what more Orozco has in store for us.

Up the Stairs and Backward in Time

Reaching the landing halfway up to el primer piso, the first upper floor, we turn to continue ascending, but become aware of a powerful presence looming over our head.

|

| Cortés y Malinche |

Hernán Cortés, the Conquistador, and Malinche, the indigenous Nahua woman given to him by her Maya master as a peace offering and who became his translator, sit naked and rigidly upright above us. Cortés stares into the distance, as if his mind is on other things, other places. Malinche drops her gaze. While they hold right hands, Cortés uses his left to block Malinche from moving forward. Below them, outside this photo (it was too dark to capture), lies the small, naked body of an indigenous man or youth, face down. Cortés´ right foot rests on the person's legs. His left foot is held poised in the air, as if about to stomp on the prostrate figure.

Artistically and emotionally, it is the simplest, most unadorned and powerful representation we have seen of the contrasts, clash, devastation and synthesis that was the Spanish Conquest of what is today called Mexico.

On the side walls leading up the stairs, Orozco continues with this potent, truly shocking theme.

|

| Los Franciscanos The Franciscans |

It was Cortés himself who, after his defeat of the Aztecs and demolition of their capital, Tenochtitlán, petitioned the young King Charles I, who was also Holy Roman Emperor Charles V, to send friars, members of religious orders, monks, not priests of the regular "secular" church, i.e. the church in the everyday world, to evangelize the indigenous peoples of the lands he was now subduing. Charles sent Franciscans. (See our post: The Spiritual Conquest: The Franciscans - Where It All Began.)

They arrived barefoot and dressed in near rags, manifesting their vows of humility and poverty. While they strove to convert the "heathen", saving them from their violent "pagan" gods, they also became known for seeking to defend them from the worst depredations of the conquistadores and peninsulares, members of the Spanish ruling class who came to manage the new realm and extract its natural wealth using indigenous labor.

Sobered by this confrontation with Mexico's roots exposed, we continue up the stairs, wondering even more how Orozco will unsettle us with the range and power both of his themes and his technique.

See more on the Mexican Revolution and Mexican Muralists

Part I: Bellas Artes

Part II: The Academy of San Carlos and Dr. Atl

Part III: Secretariat of Education, José Vasconcelos and Diego Rivera

Part IV: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Vision of Mexican Traditions

Part V: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Ballad of the Revolution

Part VI: Diego Rivera at the College of San Ildefonso

Part VIII: College of San Ildefonso and José Clemente Orozco - Continued

Part IX: David Siqueiros, Painter and Revolutionary

Part X: David Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum

Part XI: The Abelardo Rodríguez Market

For the background of the Mexican Revoluion, see: Mexican Revolution: Its Protagonists and Antagonists