From our balcony in Colonia Parque San Andrés, in Delegación Coyoacán, we can see a wooded hill, a little less than four miles straight east. It is an extinct volcano called Cerro de la Estrella, Hill of the Star. It sits in what is now the Delegación of Iztapalapa.

If you look carefully, with the help of binoculars or a telephoto lens, at the north (left) end of the fairly flat summit you can see a large white cross and a flat structure behind it. Both have stories to tell.

|

Cerro de la estrella, Hill of the Star

Huizachtecatl (Nahuatl)

Telephoto view from our rooftop.

|

The cross obviously has to do with a Christian narrative. We will get to that at a later time (See: Iztapalapa's Holy Week Passion Play). The flat structure is a Mexica temple.

|

| Temple on the summit of Cerro de la Estrella |

Toltecs of Culhuacán and Their Predecessors

The temple, in its final form, was constructed by the Mexicas (Aztecs) of Tenochtitlán, after they took over the surrounding area in 1400 C.E. However, temples had existed there from the end of the first millenium of the Common Era. They were built by the Toltec residents of the pueblo of Culhuacán (also spelled Colhuacán, “place of the culhuas”—“the ancient or venerable ones”). They settled on the south side of the hill around 600 C.E., coming from the Toltec city of Tula, north of the Valley.

The Toltecs had become the dominant power in Central Mexico after the decline of Teotihuacan (east of Lake Xaltocan) around 500 C.E. The Toltec temple on Cerro de la Estrella was dedicated to Mictlantecuhtli, God of Death and the Underworld. From their base in Culhuacán, the Toltecs dominated the east side of the lake region for some eight hundred years, until the rise of the Mexicas.

The Toltecs were not the first inhabitants of the area. Human remains dating to 9,000 years ago have been found. The first settlements date from 500 B.C.E. Some time around 150 C.E., there was an influx of people fleeing volcanic eruptions on the southwest side of Lake Texcoco that buried Cuicuilco, the earliest known urban center in the Valley (founded about 700 B.C.E). By 400 C.E., Teotihuacan made its power known on the peninsula, as evidenced by remains of builings in its style.

Location, Location, Location

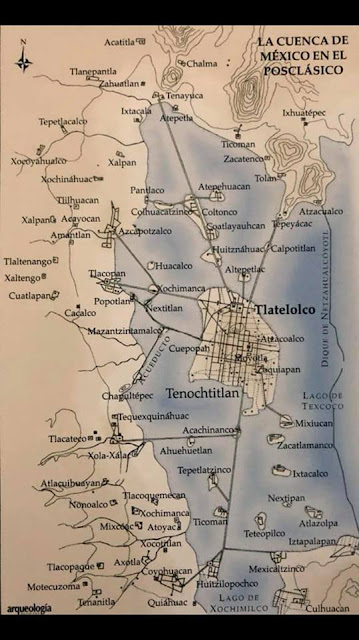

The southern end of Lake Texcoco was formed by a peninsula, separating the northern lake from Lakes Xochimilco and Chalco to the south. The peninsula was, thus, strategically located, enabling the monitoring and control of water traffic between the lakes. Cerro de la Estrella, or Huizachtecatl as the Mexica called it, sat in the middle of the peninsula. From there, one could see the all the lakes and virtually the entire valley.

|

| Cu(o)lhuacán was on the south side of the peninsula, on the north shore of Lake Xochimilco. The settlement of Iztapalapa(n) was on the north side of the peninsula, at the south end of Lake Texcoco. It stood at the end of a dike built in 1449 to separate fresh water flowing from Lakes Xocimilco and Chalco from salt water in Lake Texcoco. (The lakes have no outlet) Mexicaltzingo was another settlement at the west end of the peninsula, where the causeway, built in the 1430s, connected the peninsula with Coyoacán and Tenochtitlan. |

|

| Sierra de Santa Catarina viewed looking southeast from Cerro de la Estrella. Mt. Guadalupe, to the left, is the tallest of five cinder cone volcanoes |

|

| Center of Mexico City, viewed looking northwest from Cerro de la Estrella. Skyscrapers linePaseo de la Reforma. (Yes, on a smoggy day) |

Iztapalapa

Iztapalapa(n), on the north side of Cerro de la Estrella, fronting on Lake Texcoco, was the second major settlement on the peninsula. Earliest remains found date to the Teotihuacan era of the mid-first millenium C.E. It came under Toltec control after their arrival. When the Mexica took control in 1400 C.E., they built up Iztapalapa.

|

| Goal ring from Mexica ball court, now the site of the Church of San Lucas, Iztapalapa |

First, they constructed a causeway south from Tenochtitlan. At the narrow channel to Lake Xochimilco, the causeway split: one branch going to Coyoacán, the other to Mexicaltzingo on the end of the peninsula. Then they also built a dike across the west end of Lake Texcoco, ending at Iztapalapa, to keep fresh water flowing from Lakes Xochimilco and Chalco separate from the salty water that built up in Lake Texcoco, as the lakes had no outlet.

|

| Chac-mool, sacrificial altar now in garden of the rectory of San Lucas, Iztapalapa |

Nuevo Fuego, New Fire Ceremony

When the Mexicas of Tenochtitlan took over the peninsula, they repurposed Cerro de la Estrella. They rebuilt the temple on its summit and made it the site of one of their most important rituals, xiuhmolpilli (sheeoo-mol-PEEL-yee)—the Binding of the Years. In Spanish it is called el Nuevo Fuego, the New Fire. To grasp its significance, we need to understand how Mesoamerican people recorded time.

Two Ways of Counting Days

All Mesoamerican peoples used two calendars to organize the sequence of days in their world.

Solar Calendar

One calendar, called xiuhpohualli (sheeoo-po-WAHL-yee) by Nauhua speakers, was solar, marking the sun's 365-day cycle of movement from south to north and south again. It consisted of eighteen months of twenty days each and five additional days at the end, called nemontemi, which were viewed as highly unstable and, therefore, dangerous and unlucky. Various groups used different days to mark the beginning of each annual cyle. For the Mexicas, the new year began on February 23, just after the mid-point of winter.

Divinatory Calendar

The second calendar, actually possibly the older of the two, was called tonalpohualli (to-nahl-po-WHAL-yee). It consisted of 260 days and served divinatory purposes—rather like astrology—to determine the good- or ill-fortune of an individual or an action taken, including by those who governed. The 260-day cycle was likely based on the human gestation period—as on the day on which a person was born in this cycle, he/she was considered to have already completed one cycle of life [in the womb] and was given the name of that day. The quality of good- or ill-fortune associated with the day determined the person's fate in life.

The cycle was formed by a rotating combination of the numbers one to thirteen with a sequence of twenty day-names (Caiman, Wind, House, Lizard, Snake, etc.). When the thirteenth day—combined with the thirteenth name in the twenty-day sequence of names—was reached, a new cycle started, but beginning with the combination of the number one with the fourteenth name in the day-name sequence. Thus, each combination of name and number occurred only once in 260 days.

Fifty-two Year Cycle

The Binding of the Years, what has come to be called Nuevo Fuego, New Fire, was celebrated on the top of Cerro de la Estrella four times, in 1351, 1403, 1455 and 1507. The cycles of cosmic time and personal fate would again come to their crucial juncture in 1559.

In 1519, Cortés, his troops and indigenous allies entered the Valley. They came via what is now the el Paso de Cortés, between the volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl. When Mochtezuma finally ceded permission for them to approach Tenochtitlan, they passed through Iztapalapa, at the foot of Cerro de la Estrella, to enter the southern causeway to the city that began at Mexicaltzingo.

A year after the Noche Triste, the Night of Sorrows (November 8, 1519), in which the Spanish fled from Tenochtitlan, Cortés had regrouped his troops and prepared for the attack on Tenochtitlan. In order to regain access to the city, he needed to take the entrances to each of the causeways. So one of the major prelimiary battles occurred at Iztapalapa.

The Spanish and their indigenous allies won. The way was clear to Tenochtitlan. The Fifth Sun came to an end, not on February 23 of 1559, but on August 13, 1521.

The first days in the two cycles of time—solar and divinatory—were only aligned once every fifty-two years. This juncture was seen as an especially vulnerable moment, when it was possible that the Sun would not rise from the Underworld and hence the current world—that of the Fifth Sun—would come to an end, as had four past "Suns" and their worlds.

Binding of the Years

The Mexicas believed that the Fifth Sun—the Sun of their world—had only risen because of the self-immolation, the sacrifice of a god. The energy of the sacrificed god gave the Sun the momentum to rise from the Underworld and travel across the sky, spreading its light and heat, thus enabling life to go on. To keep the Sun rising each day—rather than remaining submerged in the Underworld—further sacrifice was required, the blood sacrifice of a human being.

|

| Mexica/Aztec Sun Stone In center is Tonatiuh, God of the Fifth Sun, the Human/Mexica Era. His tongue is a blade for human sacrifice. The four rectangles around him are the four previous Suns or Eras: From upper right, Jaguar (Underworld), Wind, Fire and Water. The symbols of the Five Suns, together with signs for the four cardinal directions-- triangle at top, the two toothed creatures, and small circle at bottom-- form the symbol of ollin (o-yeen), primal, creative energy.  The circle around the ollin contains the signs for the twenty day-names of the divinitory calendar. National Museum of History and Anthropology Photo: Ann Kingman Gomes Read more on the Sun Stone |

Thus, when a fifty-two year cycle was coming to an end, special sacrifice was necessary. When the Mexica took control of the peninsula between Lakes Texcoco and Xochimilco, they made the temple on top of Cerro de la Estrella, visible to almost the entire Valley, the site for their Binding of the Years, the tying together or conjunction of the two calendars and their reinitiation. All fires throughout the kingdom were put out. Cooking pottery was destroyed.

A priest from the campan, quarter, of Cuepopan in the northwest quarter of Tenochtitlan, led a procession down the causeway, which then ascended Huizachtecatl. On the temple platform, a captive warrior from some subjugated city was sacrificed, his heart extracted, and a fire lit in his chest cavity. From this first fire, a bonfire was lit that could be seen throughout the valley. The people then knew that their world would not come to an end for at least another fifty-two years. Torches from the fire were then carried by priests to each pueblo in the Valley, and new fires lit in the temples and every family hearth.

|

| Image from a Mexica codex, depicting the sacrifice and lighting of the New Fire. Displayed in the Museum of the New Fire, on Cerro de la Estrella |

End of the Fifth Sun

The Binding of the Years, what has come to be called Nuevo Fuego, New Fire, was celebrated on the top of Cerro de la Estrella four times, in 1351, 1403, 1455 and 1507. The cycles of cosmic time and personal fate would again come to their crucial juncture in 1559.

In 1519, Cortés, his troops and indigenous allies entered the Valley. They came via what is now the el Paso de Cortés, between the volcanoes Popocatépetl and Iztaccíhuatl. When Mochtezuma finally ceded permission for them to approach Tenochtitlan, they passed through Iztapalapa, at the foot of Cerro de la Estrella, to enter the southern causeway to the city that began at Mexicaltzingo.

A year after the Noche Triste, the Night of Sorrows (November 8, 1519), in which the Spanish fled from Tenochtitlan, Cortés had regrouped his troops and prepared for the attack on Tenochtitlan. In order to regain access to the city, he needed to take the entrances to each of the causeways. So one of the major prelimiary battles occurred at Iztapalapa.

The Spanish and their indigenous allies won. The way was clear to Tenochtitlan. The Fifth Sun came to an end, not on February 23 of 1559, but on August 13, 1521.

|

| Monument in Iztapalapa central plaza depicting the battle between Mexica eagle warriors and their allies, and the Spanish and their indigenous allies. Here, the Mexicas appear to be routing the Spanish. That, of course, is not what actually happened. |

|

| Delegación of Iztapalapa medium green to right, east of Coyoacán (dark purple in center) |

See also: