From Market to Church

At five o´clock one morning in late September, about a month after we had moved into our apartment in Colonia Parque San Andrés, in Delegación Coyoacán, in August 2011, we were startled awake by the loud explosion of cohetes, rocket-style firecrackers. Collecting our rattled wits, we realized, from our three years of living in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, surrounded by traditional pueblos, that such cohetes going off in la madrugada, pre-dawn hours, were announcing mañanitas, morning prayers, the opening event of a parish fiesta.

From their volume, the explosions were evidently from a church very nearby but of which we were unaware. The cohetes continued to go off every few hours from dawn to dusk and into the early darkness for an entire week. Some fiesta!

Besides fresh fruits and vegetables, there are also individually owned puestos, stalls, where we buy fresh chicken and dried beans of several kinds. There are deli counters for ranchero cheese (good on tortas, rolls), luncheon meats, yogurt and the like. In the "household goods" section to the rear, we can buy cleaning utensils, light bulbs, flower pots and paper goods. There is also a plumber, an electrician, a key-maker and an optometrist! At the rear is a sizeable restaurant serving basic Mexican comidas (main afternoon meal). Unfortunately, there is no bakery or fish counter such as existed in the much larger Pátzcuaro mercado.

At five o´clock one morning in late September, about a month after we had moved into our apartment in Colonia Parque San Andrés, in Delegación Coyoacán, in August 2011, we were startled awake by the loud explosion of cohetes, rocket-style firecrackers. Collecting our rattled wits, we realized, from our three years of living in Pátzcuaro, Michoacán, surrounded by traditional pueblos, that such cohetes going off in la madrugada, pre-dawn hours, were announcing mañanitas, morning prayers, the opening event of a parish fiesta.

From their volume, the explosions were evidently from a church very nearby but of which we were unaware. The cohetes continued to go off every few hours from dawn to dusk and into the early darkness for an entire week. Some fiesta!

We knew that two short blocks north of us was another colonia, neighborhood, with a typical Mexican indoor mercado, market, Mercado Churubusco. The real estate agent who showed us the apartment and arranged our rental had pointed it out to us as a convenient source of fresh foods. We had investigated it shortly after moving in, and it has been our neighborhood market ever since.

|

| Mercado Churubusco, built in the mid-20th century when the city constructed many indoor markets to bring vendors inside from the traditional tianguis, outdoor street markets. |

|

| "Luncheonette" counter at the mercado entrance Mixteca is an indigenous people from Oaxaca— hence the style of food served. |

|

| "Mickey", Miguel, with the best fresh fruits. Note the mangos! Blackberries year-round! |

|

| Arturo, his brother, with the freshest vegetables. Their father and mother sold fruits and vegetables in the neighborhood's tianguis, street market. |

Besides fresh fruits and vegetables, there are also individually owned puestos, stalls, where we buy fresh chicken and dried beans of several kinds. There are deli counters for ranchero cheese (good on tortas, rolls), luncheon meats, yogurt and the like. In the "household goods" section to the rear, we can buy cleaning utensils, light bulbs, flower pots and paper goods. There is also a plumber, an electrician, a key-maker and an optometrist! At the rear is a sizeable restaurant serving basic Mexican comidas (main afternoon meal). Unfortunately, there is no bakery or fish counter such as existed in the much larger Pátzcuaro mercado.

Crossing a frontier in time

The mercado, with all its traditional Mexican flavors, literal and cultural, is in El Barrio San Mateo Churubusco. While San Mateo, St. Matthew, has some quite upscale private homes, similar to those in San Andrés, it is mostly a lower-middle class, working-class neighborhood. It is very small, even tiny—essentially one block wide from north to south and two or three shorts blocks long east to west, between the Calzada de Tlalpan highway and Avenida Division del Norte. If one didn't live in it, or next to it as we do, you would likely not notice it or know it exists as a distinct community.

The double name, San Mateo Churubusco—combining a saint's name with an apparently indigenous one—gives a clue that it is a pueblo originario, an original indigenous village. So when we walk to the mercado, when we cross Mártires Irlandeses—Irish Martyrs? in Mexico? We'll get to that in our next post—we are crossing not just a street between neighborhoods of differing socio-economic levels, we are also crossing a frontier between modern Mexico City and the vestiges of an ancient world.

From Huitzilopochco to Churubusco

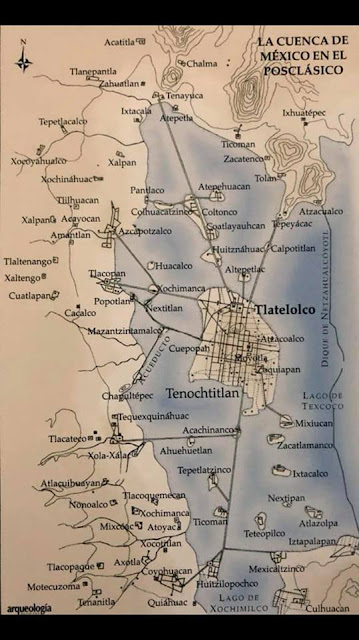

Huitzilopochco ("Wee-tzeel-lo-POCH-ko", from the náhuatl huitzitzilin, "hummingbird"; and yopochtli, "left or southern direction (based on the path of the sun)"—hence, "hummingbird from the south"), was an indigenous settlement on an island close to the southwestern shore of Lake Texcoco. It was a fishing village before the Mexicas/Aztecs of Tenochtitlan took control of the atepetls (city-states) and pueblos around the entire lake in 1430.

When the Mexica took control of the valley, they built a causeway south from their island city to the village in order to connect with Coyoacán and other important villages in the southwest part of the Valley of Anahuac. They built a temple to Huitzilopochtli there. Footpaths from there led west to Coyoacán and south to Huipulco, Tlalpan and Xochimilco. As it was located at the crossroads between these important settlements in the southwestern part of the Valley of Anahuac and Tenochtitlan, Huitzilopochco had a major tianguis, or open-air market, where goods were exchanged. So our neighborhood Mercado Churubusco has ancient roots.

The mercado, with all its traditional Mexican flavors, literal and cultural, is in El Barrio San Mateo Churubusco. While San Mateo, St. Matthew, has some quite upscale private homes, similar to those in San Andrés, it is mostly a lower-middle class, working-class neighborhood. It is very small, even tiny—essentially one block wide from north to south and two or three shorts blocks long east to west, between the Calzada de Tlalpan highway and Avenida Division del Norte. If one didn't live in it, or next to it as we do, you would likely not notice it or know it exists as a distinct community.

The double name, San Mateo Churubusco—combining a saint's name with an apparently indigenous one—gives a clue that it is a pueblo originario, an original indigenous village. So when we walk to the mercado, when we cross Mártires Irlandeses—Irish Martyrs? in Mexico? We'll get to that in our next post—we are crossing not just a street between neighborhoods of differing socio-economic levels, we are also crossing a frontier between modern Mexico City and the vestiges of an ancient world.

From Huitzilopochco to Churubusco

Huitzilopochco ("Wee-tzeel-lo-POCH-ko", from the náhuatl huitzitzilin, "hummingbird"; and yopochtli, "left or southern direction (based on the path of the sun)"—hence, "hummingbird from the south"), was an indigenous settlement on an island close to the southwestern shore of Lake Texcoco. It was a fishing village before the Mexicas/Aztecs of Tenochtitlan took control of the atepetls (city-states) and pueblos around the entire lake in 1430.

One codex relating the history of the Mexica migration through the Valley of Anahuac narrates that the settlement they called Huitzilopochco was a town originally called Ciavichilat, whose tutelary god was named Opochtli (evidently a Nahuatl name), a god of water and fishing. When the Mexica encountered the village, since their god, Huitzilopochtli, and Opochtli, "left or southern direction "—hence, "hummingbird from the south") shared the same last part of his name with the god of Ciavictilat, the two peoples agreed they must be related. The people were obviously Nahuatl-speaking and likely under the rule of Cuhuacán, across the narrow strait. Even when the Mexica took control, they continued to have Huitzilopochco administered by the former altepetl of Culhuacán.

Like Huitzilopochtli, Opochtli was also a warrior god. So, according to the legend, the people of the village agreed to change its name, first to Uichilat, and later to Huitzilopochco. Our hunch is that the change of name was not so cooperatively achieved as the codex relates but was likely imposed by the Mexica after they took control of the Valley and initiated building the causeway south across the bay in Lake Texcoco to the strategically located village. They would have wanted their god to be the overseer of this important southern access to their capital.

|

| Huitzilopochco lay at the strategic point where Lake Xochimilco emptied into Lake Texcoco. |

When the Mexica took control of the valley, they built a causeway south from their island city to the village in order to connect with Coyoacán and other important villages in the southwest part of the Valley of Anahuac. They built a temple to Huitzilopochtli there. Footpaths from there led west to Coyoacán and south to Huipulco, Tlalpan and Xochimilco. As it was located at the crossroads between these important settlements in the southwestern part of the Valley of Anahuac and Tenochtitlan, Huitzilopochco had a major tianguis, or open-air market, where goods were exchanged. So our neighborhood Mercado Churubusco has ancient roots.

After the Spanish Conquest, in 1535, the Franciscans—as part of the Spiritual Conquest—came from nearby Coyoacán to Huitzilopochco. They tore down the temple to Huitzilopochtli that stood near the entrance to the causeway. There they built a convent and church dedicated to la Asunción de Nuestra Señora, The Assumption of Our Lady(into Heaven upon her earthly death). In 1569, they abandoned the site because of lack of sufficient friars. Nevertheless, the Franciscans remained active in the area of Coyoacán, founding chapels in Hueytetitlan (now Quadrante de San Francisco, (Tres Reyes) Quiáhuac, (Niño Jesus) Tehuitzco and (San Pablo) Tetlapan, (Holy Cross) Atoyac, to the north and (San Sebastián) Axoyla, to the west.

Meanwhile, in the 1550s, the Bishop of Mexico ordered the building of a chapel in Churubusco dedicated to la Santa Cruz, the Holy Cross. It was to be a parochial church, under the bishop's direction, served by what are called secular clergy, i.e. appointed by and reporting to the bishop, rather than by the Franciscans or another religious order independent of the bishop's control.

Meanwhile, in the 1550s, the Bishop of Mexico ordered the building of a chapel in Churubusco dedicated to la Santa Cruz, the Holy Cross. It was to be a parochial church, under the bishop's direction, served by what are called secular clergy, i.e. appointed by and reporting to the bishop, rather than by the Franciscans or another religious order independent of the bishop's control.

As we have written elsewhere, this power struggle between bishops and the independent religious orders over the control of the churches in Mexico went on for some years until in the mid-18th century when the Pope gave the Bishop of Mexico control of all the churches formerly founded and run by the religious orders, turning them into parochial churches.

In 1591, the Order of San Diego, a branch of the Third Order of the Franciscans, whose first friars had arrived in Nueva España in 1576, took over the abandoned church of la Asunción de Nuestra Señora. The "Diegans", as they were called for short, built a larger church and convent dedicated to Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles, Our Lady of the Angels, that is, the Virgin Mary as Queen of Heaven after her Assumption. The church Nuestra Señora de los Ángeles and its former convent still stand a few blocks north of San Mateo Churubusco, in its sister Barrio of San Diego Churubusco, which we will visit in our next post.

The name Churubusco is thought to be a Spanish corruption of the name Huitzilopochco. How they got from one to the other is anyone's guess. Our personal hypothesis, unsupported by any evidence, is that since Huitzilopochtli was the main god of the Mexica, the Spanish wanted to obliterate any reference to him, just as they obliterated his temples and idols.

|

| Chapel of San Mateo, St. Matthew Archeologist think that a Mexica temple to Huitzilopochtli may have stood there previously. |

The Chapel of San Mateo has been renovated various times but retains its original exterior simplicity. The interior is equally simple, except for a Baroque retablo added in the 18th century.

|

| The chapel is dressed up for the annual fiesta patronal, Fiesta de San Mateo, the week of Sept. 21. |

The enclosed, paved atrio (atrium) in front of the church also extends along the north side, where it becomes a tree-shaded space that serves as a kind of plaza for the neighborhood.

The feast day for San Mateo, the gospel writer St. Matthew, is September 21. As we learned our first September in Coyoacán, the tiny barrio celebrates for an entire week. So late morning on September 21 (we aren't up for mañanitas en la madrugada, morning prayers in the pre-dawn hours), we walk the four blocks from our apartment to the chapel of San Mateo.

|

| Tapete de aserrín, sawdust carpet Depicts the Virgin of Guadalupe surrounded by roses and colibrís, hummingbirds. |

Arriving at the calleja, narrow street, in front of the chapel, we are greeted by a traditional tapete de aserrín, a carpet of colored sawdust. It displays an equally traditional Virgen de Guadalupe, the mestizo (mixed-race) Holy Mother of Mexico, who united the indigenous people and the Spanish faith. She is surrounded by roses, a symbol of the Virgin, and colibrís, hummingbirds. They are a subtle but explicit symbolic reference to the original indigenous name of the community, "Hummingbird of the South".

|

| San Mateo as a Mexica/Azteca Eagle Warrior |

Farther along the street is another tapete. This one is even more explicit and surprising in its reference to the community's indigenous orgins—portraying the Christian St. Matthew as a Mexica/Azteca Eagle Warrior. Eagle Warriors, along with Jaguar Warriors, were one of the two elite corps in the Mexica army. Talk about the fusion of traditions!

|

| "St. Matthew, bless us." Portada, of artificial flowers, decorates the entrance to the atrio. |

Passing beneath the portada decorating the entrance to the atrio, we find that preparations for the fiesta have not quite been completed.

|

| Shaking sawdust to create another tapete, this one portraying the chapel. |

|

| Two castillos, "castles" for evening fireworks. A third castillo is being assembled, as there will be fireworks for three nights. |

Nevertheless, the fiesta is already in full swing. We have just missed a dance performance.

|

| Aztec danzante tunes his lute, another gift of the Moors to Spain, and the "Western" world. |

|

| Mixture of indigenous and "Western" instruments. Plumed Serpent on the rear drum is the god, Quetzalcóatl. |

An Aztec danzante group has just finished. Such groups frequently appear at fiestas in Mexico City and sometimes perform in public plazas. We once saw dozens of them performing in the plaza at the Basilica of the Virgin of Guadalupe, after which they entered the Basilica for a Mass said on their behalf. Each group represented a specific pueblo or barrio around the City, so each pueblo was being honored and blessed as much as each group of danzantes. (See our post: Traditional Indigenous Dancers: Concheros and Danzantes Aztecas

But we are not disappointed for long.

|

| Chinelos, dancers in Moorish-style "disguises". These dancers come from a pueblo on Mt. Ajusco, several miles south, at the southern boundary of the City. |

|

| Caporales, cowgirls, twirl |

The chinelos are followed, in turn, by a group of caporales, cowgirls and cowboys, in their Spanish-Mexican dress. So we have already experienced four cultures: Indigenous, Moorish, Spanish and their Mexican synthesis!

|

| Tradition lives on! |

|

| And, of course, accompanied by la banda! |

|

| Enjoying the fiesta, with chinelo puppet. |

|

| "Super papa," Granddad and grandson |

The performances then segue into the next event:

|

| La banda leads off into the procession. Note the presence of yet another culture! |

|

All-important coheteros

go several yards in front....

|

|

...announcing the approach

of the procession

|

|

| "Long live San Mateo" and his pueblo, (people/village) |

|

| Our Lady of the Angels, from neighboring San Diego Churubusco, joins the procession. |

From Church Back to Market

The procession moves down the narrow calleja at the side of the chapel, passing the market.

|

| The Churubusco Mercado, has been freshly painted by the recently elected government of Delegación Coyoacán, The sign, upper left, reads, "Coyoacán: Tradition and Vanguard" The City government has pledged financial support for the traditional mercados in the face of competition from Walmart and other "supermercados". |

|

| Sacred and Secular, Church and Mercado, the core combination of Mexican pueblo identity. |

Circling that other center of community life, el mercado, the procession moves along Calle Mártirés Irlandeses, bringing us back to where we began, the corner of Calle California that is the entrance to Colonia Parque San Andrés. So here we part ways with traditional Mexico and our neighboring pueblo originario, San Mateo Churubusco, and head home to modern Mexico City.

|

| Pues, well, fronteras (frontiers, borders) are rather porous in Mexico. Around the corner from el mercado, on California Street in upscale Parque San Andrés, a family sets up business selling rolls and fresh quesadillas, Here, they are traditional blue corn tortillas, baked on a comal (grill, originally of stone, now sheet metal, heated by a portable tank of gas), and filled with various veggies and cheese. Note the Mexican ingenuity of using tires to hold up the umbrellas of their portable enterprise. The tianguis (ancient open-air market) lives! |

|

| Delegaciones of Mexico City Coyoacán is the purple delegación in the center. |

|

| San Mateo Churubusco is small, green area just to the right (east) of the star. Parque San Andrés is Mexico City Ambles' home base. |

See also:

Mexico City's Original Villages: Introduction - Landmarks of the Spiritual Conquest

The Spiritual Conquest: The Franciscans - Where It All Began

Mexico City's Original Villages: Coyoacán's Many Pueblos

Coyoacán: Pueblo of Tres Santos Reyes and the Lord of Compassion

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Goes Visiting

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Visits Barrios San Lucas and Niño Jesús, the Child Jesus

Coyoacán: Pueblo Candelaria Welcomes the Lord of Compassion

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Travels from San Pablo Tepetlapa to Santa Úrsula Coapa

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Returns Home to Pueblo Tres Santos Reyes

No comments:

Post a Comment