In 1920, as the power struggles between leaders of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) were still playing themselves out, General Álvaro Obregón, who had defeated Pancho Villa and Emiliano Zapata on behalf of Venustiano Caranza, overthrew his former Jefe, boss, and became President.

One of his first acts was to create the Secretariat of Public Education (SEP) and select José Vasconselos (1882-1959), lawyer, amateur philosopher and staunch supporter of the Revolution's ideals, to head the new institution.

The Secretariat took as its headquarters the former convent of Santa María de la Encarnación del Divino Verbo (St. Mary of the Incarnation of the Divine Word). Built in the 1640's, it was one of the largest and richest convents in Spanish Colonial Mexico City (nuns, who had to be pure-blooded Spanish, had their own apartments and servants). During the Era of Reforms led by President Benito Juárez in the 1850s and 60s, such Church properties were nationalized and put to secular uses. The convent was used for various government purposes. It sits just behind the Metropolitan Cathedral in the Centro Histórico.

|

| Secretariat of Public Education corner of República de Argentina and San Ildefonso Streets |

When Vasconcelos took over the edifice, he had it renovated in Neoclassic style to express the liberal ideals of the Enlightenment (think Washington, D.C.). He saw its two huge, open interior patios as spaces to display his vision of a post-Revolution Mexican identity, synthesizing its indigenous past with elements of its Spanish culture and modern, secular life through empirically based, humanistic, free public education.

To execute this huge artistic and cultural project, Vasconcelos encouraged a pre-Revolution acquaintance, Diego Rivera, to return from Europe. Throughout the period of the Revolution, Rivera had been in Europe studying and painting with Impressionist and modern masters. At age thirty-seven, Rivera agreed to return to Mexico City. From 1923 to 1928 Rivera painted murals on virtually every wall of every floor of the two patios.

|

| Front patio, which Rivera designated The Patio of Labor |

The building has three floors, in Spanish la planta baja (ground floor) and primer y segundo pisos (first and second floors). On the ground floor of the front or east patio, Rivera mostly painted murals portraying Mexican workers or laborers. He therefore named the patio el Patio del Trabajo, The Patio of Labor. It is here that our tour begins. We will see that it presents more than workers. It initiates us to the ideals of the Mexican Revolution.

| Diego Rivera self-portrait while in Europe Dolores Olmedo Museum, Delegación Xochimilco, Mexico City |

"Land and Liberty"

One dynamic driving the Revolution—represented in the rural-based forces of Emiliano Zapata and Francisco "Pancho" Villa—was the peasants' demand to be freed from virtual slavery as peons on the haciendas. During the Colonial Period, the King of Spain granted these large estates to his soldiers. The peasants' Revolutionary demand was that the land—theirs as indigenous inhabitants—be returned to them.

|

| Liberation of the Péon |

|

| Distribution of the Land A government official, moreno, dark-skinned, hence of indigenous origins, oversees light-skinned, hence criollo (of pure-blooded Spanish descent) hacendados, landowners, as they sign over land titles to an ejido, a community of indigenous moreno campesinos, peasant farmers. |

|

| An idealized, ladino (middle class, Europeanized) Emiliano Zapata looks on as land is distributed. In fact, Zapata was assassinated by agents of victorious President Venustiano Caranza in April 1919. |

Along with the demand for land went the desire for economic and political liberty. Central to that liberty was being able to read and write in order to participate as equals in business dealings and in organized political activity.

Educating rural, poor, often indigenous campesinos, peasant farmers, was a truly revolutionary idea. President Benito Juárez, himself indigenous, had the goal of establishing secular (non-Catholic), free public education during the brief Era of Reform (1856-76). However, his administration was fragmented by two periods of civil war initiated by conservative forces, the War of Reform (1857-60) and the French Intervention (1862-67).

In 1868, Juárez established the National Preparatory (High) School in the former Jesuit Colegio de San Ildefonso, just down the street from Santa María de la Encarnación. However, with the return of domination by conservative, wealthy hacendados, owners of haciendas, during the reign of President Porfirio Díaz (1876-1911), any thought of educating rural people was banished.

|

| The Rural Teacher instructs all ages, under the watchful eye of a Revolutionay soldier |

Thus, central to the vision of the rural revolution of Zapata and Villa was education of the campesinos. To this end, Vasconcelos established Rural Normal Schools, whose mission was to train indigenous youth from rural pueblos to become teachers. In turn, they would return as teachers to their villages to educate their people. The history and vicissitudes of these Rural Normal Schools reflect the ongoing conflicts between conservative oligarchic and populist forces in Mexico up to the present day.

The Weight of Labor

Rivera's portrayals of various groups of laborers do not contain explicit political messages. However, his rendering of their bodies, with their postures and evident weight, together with the color tones he chose, communicates the physical and emotional tenor of their lives.

|

| Entrance to the mine |

|

| Exit from the Mine raised arms of worker being searched as he leaves reflect a crucifixion |

|

| The Sugar Mill Here the rhythm of heavy physical work is conveyed |

|

| The Hacienda Foreman postures say it all |

|

| The Dyers slow rhythms of repetitive work |

|

| Campesinas, Rural Women stoic stillness, each pair a kind of pyramid |

|

| The Embrace, between urban day laborer and day farm worker An explicit revolutionary message |

|

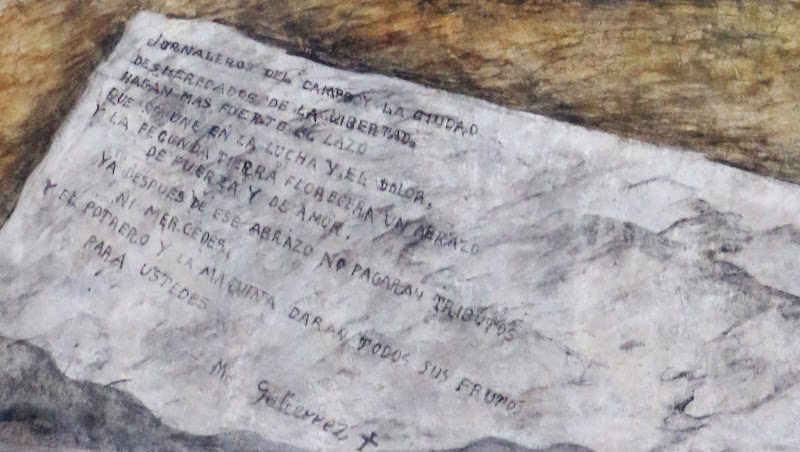

| The dayworkers of the fields and of the city, both disinherited from liberty, make stronger the tie that unites them in the struggle and in pain and the fecund earth gives flower to an embrace of force and love. Now after this embrace they will not pay tributes or favors, and the field and the machine will give all their fruits to all of you. M. Gutierrez (Manuel Gutierrez, governor of Veracruz and liberal politician during the Era of Reform) |

|

| And on all this, Rivera put his own stamp. |

Rivera signed each mural accompanied with a symbol: the hammer of the laborer and the sickle of the farmworker. The emblem of Communism, which sought the embrace of workers from the city and the countryside. We will see touches of this perspective when we tour Rivera's murals in the second patio portraying traditional festivals, which he named the Patio of the Fiestas. We will encounter it in full force when we reach the top floor of this edifice where a lawyer and a painter sought to realize a Revolutionary vision.

See more on the Mexican Revolution and Mexican Muralists:

- Part I: Bellas Artes;

- Part II: The Academy of San Carlos and Dr. Atl;

- Part IV: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Vision of Mexican Traditions;

- Part V: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Ballad of the Revolution;

- Part VI: Diego Rivera at the College of San Ildefonso;

- Part VII: José Clemente Orozco Comes to San Ildefonso;

- Part VIII: College of San Ildefonso and José Clemente Orozco - Continued;

- Part IX: David Siqueiros, Painter and Revolutionary;

- Part X: David Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum;

- Part XI: The Abelardo Rodríguez Market.

See also: Diego Rivera: European Apprenticeship & Mexican Homecoming from my wife's, Jenny's Journal of Mexican Culture.

No comments:

Post a Comment