|

| La Danza del Venadito Dance of the Little Deer |

La Danza del Venadito, The Dance of the Little Deer, presents us with a ritual of the hunter-gatherer culture that preceded the agrarian, settled culture based on cultivation of corn, maíz. It is curious in Rivera's painting that the musicians and male onlookers at the left appear to be in uniform, perhaps setting the event in the context of the Revolution. On the right, women wrapped in traditional tilmas, shawls, look on.

|

| La Cosecha del Maíz Harvest of the Corn |

Corn, maíz, is the foundation of Mexican culture. Domesticated some 5,000 years ago in the Balsas River Valley of southern Mexico, its productivity and capacity to be stored and used in multiple foods and drinks provided the basis for development of the numerous Mesoamerican civilizations that emerged in what is now Mexico and Central America. Rivera paints these figures with the same feeling of reverence that he gives the workers in the Patio of Labor.

|

| La Fiesta del Maíz Corn Festival |

As the sustainer of life and culture, corn was the gift of a god in Mesoamerican societies. After the Spanish Conquest, this reverence was merged with Roman Catholicism. The form of the cross in the painting embodies this syncretism, as it represented the tree of life in indigenous culture and, of course, Christ's self-sacrifice.

|

| La Danza de los Listones Dance of the Ribbons |

La Danza de los Listones, Dance of the Ribbons, is frequently enacted in Mexico Folkloric Dance performances. It has roots in harvest festivals, with the central figure representing the elote, the ripe tasseled ear of corn. It was performed at weddings, with the groom portraying the ripe corn.

|

| La Zandunga: Traditional Oaxacan Dance |

|

| Tianguis Street Market |

Moving beyond festivals to other dimensions of Mexican life rooted in pre-Hispanic, indigenous culture, Rivera gives us a triptych, three murals, of the tianguis, the traditional street market, whose modern version still thrives from Mexico City to the smallest pueblo.

|

| Tianguis Street Market The man in the soft sombrero could well be Rivera |

|

Tianguis

The dog is a Xoloitzcuintli, the indigenous Mexican HairlessStreet Market |

In other murals of sacred celebrations, Rivera carries us into a more complex level of the mixture of traditional and contemporary Mexican culture.

|

| Día de los Muertos Day of the Dead Cempasúchitl, marigold flowers, native to Mexico, cover the arches and the cross, again a synthesis of the Tree of Life and the 'Tree' of Jesus' death. |

The traditional Mexican celebration most well-known among non-Mexicans is perhaps Día de los Muertos, Day of the Dead which is, once again, a synthesis of indigenous Mesoamerican and Catholic ritual.

|

| Día de los Muertos, Fiesta en la Calle Day of the Dead Street Festival |

In Mexico City, and perhaps in other large cities, the traditional, subdued, family-centered honoring of the deceased in cemeteries and at home has evolved into rather more of a public party held in the streets and plazas.

|

| Calacas, skeletons—here in the form of marionette vaqueros, cowboy musicians—play and dance. Behind them are pyramids of calaveras, skulls, usually made of sugar. The large calaveras represent a bishop, a general and a businessman |

Calacas, skeletons, and calaveras, skulls, presented in darkly humorous forms, are typical of Mexicans' ironic and satirical sense of humor.

On the right side of the painting, a more sedate crowd, including Rivera himself, with his distinctive round face and soft sombrero.

|

| Viernes de Dolores en el Canal de Santa Anita Friday of Sorrows (prior to Palm Sunday) on the Santa Anita Canal, Mexico City |

The Friday before Palm Sunday is Viernes de Dolores, the Friday of Sorrows, which honors the sufferings of Jesus' mother, the Virgin Mary. In his portrayal of the holiday market of Semana Santa, Holy Week, Rivera again brings together the traditional—all the colorfulness of its flowers, dress and flat-bottomed trajinera boats of an ancient Aztec canal—with a lone, totally modern, blond tourist in her sensuous 1920s flapper dress. A subtle clash of eras and cultures.

|

| La Quema de Judas The Burning of Judas Holy Saturday Young men tear up paving stones to throw at the exploding figures. |

Another Semana Santa festival is La Quema de Judas, the Burning of Judas, which takes place Holy Saturday night between the sorrow of Good Friday and the joy of Easter Morning. It centers on the explosion of larger-than-life papier maché figures wrapped with firecrackers and Roman candles and hung on lines over the street. Traditonally, figures of the betrayer, Judas, were burned, but this developed into burning in effigy any person or representatives of groups of persons disdained by el pueblo, the common people. In the midst of the solemnities of Semana Santa, it is a time of great hilarity, rather like Carnaval (Mardi Gras) before Lent.

In this Quema a bourgeois businessman, a soldier and a priest are burned. The young men throwing paving stones at them adds to the sense of eruption of anger verging on un desmán, a riot.

Two final murals in the Patio of Fiestas directly present this sense of eruption of underlying indignation and outrage from los de abajo, those below, and from behind or within the apparent tranquility of traditional popular rituals. The murals portray not an agricultural or religious festival, but a modern, secular political event: International Labor Day.

|

| The International Labor Movement brings together all races, dark-skinned Latin Americans with "güero", fair-skinned northerners. |

|

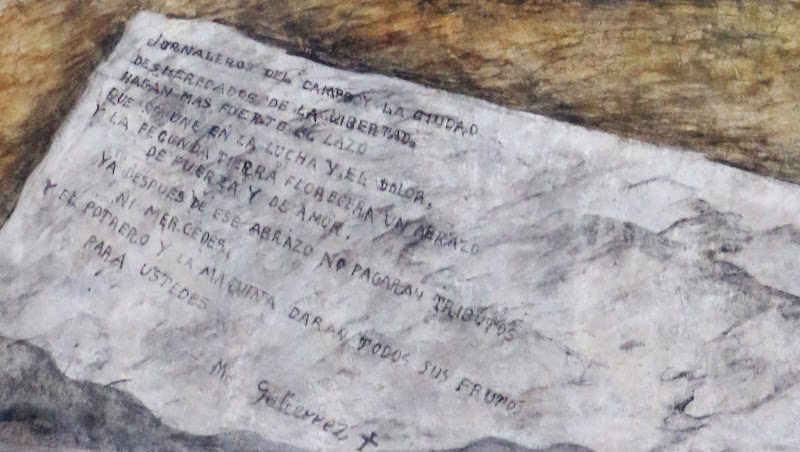

| Land and Liberty League of Agrarian Communites of the New People |

And so we come face to face with the Mexican Revolution. This is but a prelude to what we will encounter on the top floor of the Secretariat of Public Education—the creation of José Vasconcelos, its founding secretary and Diego Rivera's patron.

See more on the Mexican Revolution and Mexican Muralists:

Part I: Bellas Artes

Part II: The Academy of San Carlos and Dr. Atl

Part III: Secretariat of Education, José Vasconcelos and Diego Rivera

Part V: Secretariat of Education and Diego Rivera's Ballad of the Revolution

Part VI: Diego Rivera at the College of San Ildefonso

Part VII: José Clemente Orozco Comes to San Ildefonso

Part VIII: College of San Ildefonso and José Clemente Orozco - Continued

Part IX: David Siqueiros, Painter and Revolutionary

Part X: David Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum

Part XI: The Abelardo Rodríguez Market

For the background of the Mexican Revoluion, see: