Discovering More Original Pueblos in Delegacion/Alcaldía Iztapalapa

Some of our first ambles, beginning in 2016, to original indigenous pueblos outside our home base of Coyoacán were to Delegación (now Alcaldía) Iztapalapa. It is just to our east and we can see the historically important Cerro de la Estrella (Hill of the Star) from our balcony. We can also see the fireworks from the many fiestas held in Pueblo Culhuacán, southwest of the Cerro (about 2.5 miles away) and its eight barrios. We have also visited the original altepetl (city-state) that is now the governmental center of Iztapalapa, which is just north of the Cerro. So we have gotten to know that western part of the large delegación pretty well, pretty quickly.

Hence, we were surprised, a year ago, in 2018, to discover that there are several other original pueblos in other parts of the delegación. One is a group that were originally islands in Lake Texcoco, north of the original center of Iztapalapa. These pueblos are in the northwest corner of the modern delegación, near Coyoacán, hence convenient for us to visit.

Yet another group lies far to the eastern end of the delegación, some eight miles from us, near the border with the State of Mexico, at about what was once the middle of the north shore of the peninsula. The peninsula's other half now lies within that neighboring state. There are five pueblos in the group: Santa Martha Acatitla, San Sebastián Tecoloxtitla, Santa María Aztahuacan, Santiago Acahualtepec and Santa Cruz Meyehualco.

We stumbled across these pueblos because we saw their announcements on Facebook of the Carnivals that they hold in the spring leading up to Easter. We were able to attend one, in Santa Martha Acatitla, in February 2018, and had a marvelous time. We had hoped to attend others, but other aspects of our life took precedence. We had to accept that we would have to wait for when the other four pueblos held their patron saint fiestas or for their Carnivals a year later to have the opportunity to become acquainted with them and to learn something of their indigenous and post-conquest histories.

San Sebastián Tecoloxtitla

As it happens, without our knowing it, we actually had encountered Pueblo San Sebastian Tecoloxtitla. on our way to Santa Martha Acatitla, we had run into a comparsa de charros, a group who parade through the streets to the music of a banda, dressed in elaborate Spanish cowboy suits embroidered with a multitude of symbols done in expensive gold thread. Such a suit can cost from US$2,000 to US$3,000.

They also often wear masks that are exaggerated portrayals of wealthy Spanish hacendados, owners of haciendas. These were large rural estates created out of land granted by the Spanish crown or taken by hook or crook from the indigenous peoples, on which the indigenous then had to do all the work as peons for little pay. We had met such charros from the Barrio de San Francisco Culhuacan at another fiesta in Coyoacán early on in our ambles.

At that time we met the Charros de San Francisco, we wondered why cowboys were a meaningful symbol in the Valley of Mexico, which, as far as we knew, after the Conquest, had been largely composed of lakes and agricultural land, including chinampas, man-made islands, for growing corn and other crops for the City of Mexico. Cattle ranching went on in the western regions of Nueva España, such as in what is now the state of Jalisco, famous for its charros, and northern states such as Sonora. We also wondered why the descendants of the peons would want to imitate their ancestors' wealthy, leisure-loving Spanish bosses.

Without knowing it, to get to Santa Martha Acatitla we had had to pass along the border of Pueblo San Sebastián Tecoloxtitla. About halfway along Avenida Mexico, the side street leading from the main boulevard, Avenida de las Torres to Santa Martha, the street was closed off to cars, which is typical for fiestas. So we had gotten out of our taxi and started walking. Almost immediately, we saw a group of charros marching towards us, to the accompaniment of a banda. We assumed they were part of the Carnival of Santa Martha and joined them, taking many photos of their elaborate attire and strong faces.

|

| Comparsa de charros from San Sebastián Tecoloxtitla, marching along Ave. México. |

We got so engrossed in taking photos that we were not immediately concerned that they were marching away from Santa Martha. Often marches or processions circle around a pueblo before returning to its central point, the church. However, when they reached Ave. de las Torres and crossed the four-lane road, we began to wonder about their destination, so we asked one of the charros. He told us they were from San Sebastián, not neighboring Santa Martha, and they were headed to meet another comparsa from a third pueblo, Santa María Aztahuacan, which lay across the main boulevard we had just crossed. Their march had nothing to do with the Carnival in Santa Martha.

|

| The comparsa de charros from Santa María Aztahuacan arrive to greet the comparsa from San Sebastian Tecoloxtitla |

Embarrassed by our misunderstanding, we asked the way to Santa Martha and they pointed us back along Ave. Mexico, naming another street where we should turn right to reach our desired destination.

So we retraced our steps and eventually arrived at the church in Santa Martha, thankfully well in time for the Carnival. As a result, we had lots of great photos of these charros from San Sebastián, but no idea of what to do with them, since we had no context about the pueblo to incorporate them in a post. So we saved them in a Google album and hoped sometime we would find a way to share them. The opportunity finally came some ten months later, with the patron saint fiesta for San Sebastián, which occurs on January 20. This time we could return to San Sebastián knowingly and with a fiesta to provide context for our photos.

Patron Saint Fiesta of San Sebastián Tecoloxtitla

The patron saint fiesta fell on a Sunday this year. So that Sunday morning we call our regular taxi sitio (stand). The driver who arrives is young and not one we know, so, for a moment, we wonder if he will want to drive the eight miles across Iztapalapa, It's a pretty straight shot by the wide Avenida Ermita-Iztapalapa. Happily, he is totally agreeable to doing so. He even sticks with us when we arrive at the southeastern end of San Sebastián and begin searching for the church. It takes a bit, as the church is in the far northwest corner of the pueblo, not, as is most common, near its center. There, we pay our driver and thank him for his willingness to bring us so far and for his persistence in locating the church.

|

| Similarly, bouquets are used over the atrio (atrium) entrance. |

|

| Adjacent to the church atrio is a large sports field. On one of its walls is this idyllic mural depicting the Iztapalapa Peninsula in its agricultural heyday, which lasted through the first half of the 20th century. The snow-capped mountain to the left is the Volcán Iztaccíhuatl, Nahuatl for the White Woman. The smoking cone volcano to the right is Popocatépetl, "Smoking Mountain". The smaller volcanoes in front of them are the Sierra Santa Catarina, which were originally near the southern edge of the peninsula. They now form the border between Delegaciones/Alcadías Iztapalapa and Tláhuac. (See our posts: Encountering Mexico City's Many Volcanoes: Part I and Part II. |

Charros, Charros and More Charros

The fiesta announcement stated that there would be a parade of charros after Mass, which was the main incentive for our coming. It gave an address where the parade would start. Asking around, we learn that the street is just one block east of the church. Walking there, we spot a couple of charros striding quickly down the street, obviously to the parade starting point. We confirm with them that that is their destination and follow them.

They lead us to a small house with a driveway/patio space to one side where folding tables are set up and charros are eating. We are invited to join them for the usual comida of boiled beef and tortillas. When everyone has finished, the tables are put away. A banda appears and begins to play. The charros begin to dance in the small space beside the house. The confined space doesn't deter them from getting into the rhythm of the simple dance. But then they leave to undertake a parade through the streets. So we photograph them as they are, dancing in the patio.

What is most fascinating about the charros is, of course, their elaborate and fanciful attire.

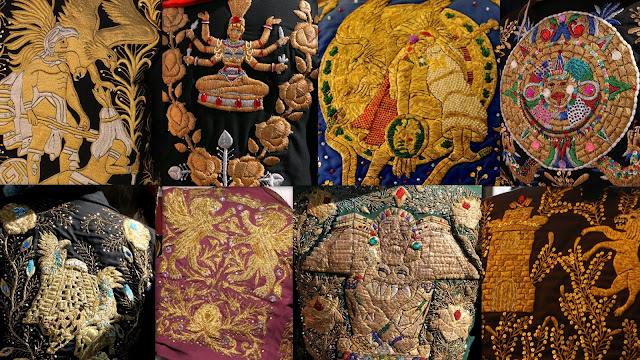

While the front of their jackets and masks are extraordinary works of art, it is the backs that provide room for the most elaborately embroidered and varied symbolic representations.

Just People

As always, we are fascinated by faces and taking retratos, portraits of just people.

The History and Meaning of Charros

Above all, our two forays into San Sebastián Tecoloxtitlan led us to meet numerous comparsas de charros in all their finery. Their use of a mixture of symbols, from Hindu gods, through medieval European heraldry to Aztec warriors and gods to "Western" cowboys and "Indians", fascinates and puzzles us.

We asked various charros why they choose clearly upper-class Spanish attire. Their answer is it is a burla, a mockery or taunting of the hacendados, hacienda owners, for whom their antepasados, ancestors, worked as peons, a kind of symbolic turning of the tables.

We asked various charros why they choose clearly upper-class Spanish attire. Their answer is it is a burla, a mockery or taunting of the hacendados, hacienda owners, for whom their antepasados, ancestors, worked as peons, a kind of symbolic turning of the tables.

As for charros and caporales or vaqueros (cowboys) in the Valley of Mexico, they are not an anomaly. We have since learned that many of the haciendas created in the Valley, beginning in the 17th century, raised herds of beef cattle numbering into the thousands on the land that had formerly been lakebed. It made great pastureland. Alfalfa was also raised to feed the cattle and thousands of horses.

Some of these haciendas survived not only Mexican independence from Spain (1821) but also the Mexican Revolution (1910-1917) which led to the expropriation of some land and its return to original indigenous pueblos as ejido, communal land. The last haciendas were only dissolved in the mid-20th century, when urban population growth made selling the land to developers worth more than the work involved in maintaining large ranches.

As for the wide-ranging symbols, the charros told us each one gets to choose the designs on his jackets and pants. All the symbols have to do with power, whether of gods, warriors or royalty, regardless of their cultural origin. Their synthesis with quintessential Spanish dress is a quintessentially Mexican one of originally opposing cultures.

Oh, and there is a whole cottage industry of women who make and embroider the expensive but much-desired costumes. That, too, is very Mexican.

Oh, and there is a whole cottage industry of women who make and embroider the expensive but much-desired costumes. That, too, is very Mexican.

Delegación of Iztapalapa

medium green to right, east of Coyoacán (dark purple in center) |

No comments:

Post a Comment