Culhuacán's Lord of Calvary, the Black Christ, Buried

- The first focused on its history as an original indigenous altepelt (city-state) that for hundreds of years controlled the southeast side of Lake Texcoco and the north side of Lake Xochimilco before the rise to power of the Mexica of Tenochtitlan in 1430.

- Our second post told of our Amble through Contemporary Culhuacán and its vestiges of the Spirtual Conquest, i.e. the conversion of its indigenous inhabitants to Catholic Christianity by Spanish friars. This led to our first encounter with el Señor del Calvario, the Lord of Calvary, in His Capilla, Chapel, in the center of what is now Pueblo Culhuacán. El Señor is a carved image of Jesus as the Christ during the day and a half He was buried in His tomb—and when, according to the Apostle's Creed, "He descended into Hell." And He is black.

Chapel of the Lord of Calvary, the People's Creation

|

| Chapel of the Lord of Calvary Note: the space behind the altar is empty. There is no figure of Christ, something we wondered about at the time. |

The chapel was built by local residents around the turn of the 19th to the 20th century—that is, it is a creation of religión popular, religion of the people, el pueblo. It is not an establishment of either the official Catholic Church or of any religious order—as were both the nearby former Convent of St. John the Evangelist, built by the Augustians in th mid-16th century as part of their work to convert the indigenous in the so-called Spiritual Conquest, and the adjacent Parrochial Church of St. John the Evangelist, built near the end of the 19th century to replace a church attached to the original convent that had fallen into disrepair.

Nevertheless, despite the chapel's relative newness, the sacred origins of the site go back some centuries. It is located next to a small cave in the adjoining hillside which is the base of a small, extinct volcano called Cerro de la Estrella (Hill of the Star). Volcanic action created many caves in the hillside. The summit of the hill is the site of the Mexica temple of the Binding of the Years or New Fire that we wrote about in our initial post on Culhuacán and its neighbor, Iztapalapa.

This cave was evidently the site of indigenous rituals to gods of the Underworld. In our first post on El Señor, we wrote about the indigenous tradition of black gods, including Tezcatlipoca, god of the night, hurricanes, the north (cold), the earth, enmity, discord, temptation, sorcery, war and strife.

Nevertheless, despite the chapel's relative newness, the sacred origins of the site go back some centuries. It is located next to a small cave in the adjoining hillside which is the base of a small, extinct volcano called Cerro de la Estrella (Hill of the Star). Volcanic action created many caves in the hillside. The summit of the hill is the site of the Mexica temple of the Binding of the Years or New Fire that we wrote about in our initial post on Culhuacán and its neighbor, Iztapalapa.

This cave was evidently the site of indigenous rituals to gods of the Underworld. In our first post on El Señor, we wrote about the indigenous tradition of black gods, including Tezcatlipoca, god of the night, hurricanes, the north (cold), the earth, enmity, discord, temptation, sorcery, war and strife.

Legend has it that a couple of hundred years ago, the carving of the entombed black Christ was found in the cave.

|

| Cave of the Lord of Calvary Note: the glass coffin is also empty. |

A large mural on the side wall of the Chapel depicts the religious meaning of this intriguing set of symbols and their location.

|

| The black Lord of Calvary is worshipped in his cave by indigenous people. There are no Spaniards or Catholic priests (although the goat is a European introduction). Cerro de la Estrella rises at the top, in the background. |

Binding el Pueblo, the People of Culhuacán-Tomatlán Together

Our third post on Culhuacán recounted our second encounter with el Señor del Calvario, during the Fiesta de la Santisima Trinidad, the Most Holy Trinity, celebrated in June after the end of Easter Season. That Sunday, after joining in a long procession through all four barrios of Pueblo San Francisco Culhuacán, on the Delegacion (borough) Coyoacán side of greater Culhuacán, we arrived at the Chapel of the Lord of Calvary for an outdoor mass, joined by people from the five barrios of Pueblo Culhuacán, in Delegación Iztapalapa.

At the beginning of the Mass, El Señor del Calvario was carefully carried in his glass coffin from His place above the altar of His chapel and placed on a table at the front, where he was joined by the saints brought from all the barrios of both Culhuacáns. It was dramatically clear that El Señor is The Saint, the symbolic figure, that binds all the barrios of Culhuacán together. He is the unofficial, but very powerful Saint of Culhuacán.

El Señor Visits His Barrios

As we kept track of the fiestas of Culhuacán, (via the Facebook page, Fiestas Mágicas del los Pueblos y Barrios Originarios del Valle de Mexico, Magical Fiestas of the Original Villages and Neighborhoods of the Valley of Mexico) we noted that El Señor del Calvario goes visiting to the various pueblos and barrios of Culhuacán. Thus, He is similar to his counterparts, El Señor de Misericordia, the Lord of Compassion, in central Coyoacán, and el Niño 'Pa in Xochimilco, but unlike these other two, His visits coincide with the fiesta patronal, the patron saint fiesta, of each community. This, perhaps, explains why His place in His chapel was empty the first time we visited.

Thus, when we saw on the announcement of the Fiesta de San Andrés Tomatlán (held the week of Nov. 30, when we participated in its procession) that the final event was el traslado del Señor del Calvario desde San Andrés hasta Santa María Tomatlan, the transfer of the Lord of Calvary from Pueblo San Andrés to Pueblo Santa María Tomatlán, we were determined to return to San Andrés to witness this very significant act. Clearly, El Señor´s presence in the Church of St. Andrew during its fiesta and His transfer to St. Mary's for that parish's fiesta, celebrating the Immaculate Conception of Mary (Dec. 8), meant the Pueblo Tomatlán, just south of Pueblo Culhuacán, was part of the larger Culhuacán commuity, part of a larger pueblo. The transfer was scheduled for four o'clock, Tuesday afternoon.

Waiting

At about twenty minutes to four, we get off the Metro at the San Andres Tomatlán station. From the elevated platform, we can see that the church's gate is closed and no one is in the atrio (atrium) inside. A bit anxious as to whether the event is actually going to occur, we descend to Avenida Tláhuac, cross and ascend the stairs to the church. While the iron gate to the atrio is closed, we find it is unlocked, so we enter and climb the remaining stairs to the front of the church.

|

| Fiesta de San Andres' floral portada. "Congratulatons, St. Andrew, on your day." The sun is, of course, one of the most ancient of religious symbols. |

The large wooden doors to the sanctuary are closed and locked. So, too, is the door to the Chapel on the right side. Our anxiety growing, we walk around to the other side of the church and find a glass door to the church office. A sign says it is open from 9AM to noon and again from 4PM to 7. The break is a typical one in Mexico for comida, the main meal of the day, preferably eaten at home with the family. As it is now a few minutes before four, we decide to sit on the steps and wait, and maintain hope.

Suddenly, promptly at four, a large suburban vehicle drives in through a second gate that is open to a side street. We recognize the driver as the mayordomo, the head of the mayordomia, the committee in charge of the fiesta. Right behind him is a taxi with three or four other members of the mayordomia. As the mayordomo gets out of his car, we go over and greet him. He remembers us from the procession last Thursday and welcomes us, assuring us that el traslado del Señor is going to happen. Other people arrive on foot. I chat with some of them while we wait for whatever is next.

Meeting el Señor del Calvario

Suddenly, someone inside opens the doors to the sanctuary and everyone enters. The sheer number of bouquets of flowers—predominantly lillies—filling the modern, high-ceilinged space is almost overwhelming—as is, may we add, their scent. In the center rests the glass casket of El Señor. Next to it rests another, much smaller glass casket.

|

| Casket of el Señor del Calvario |

|

| El Señor del Calvario The wrapping—hand-embroidered by ladies of the parish—is changed at each transfer of El Señor. A woman of the parish informs us that the "dressing" was done at 7 AM this morning. |

|

| El Señor del Calvario |

More Waiting

After taking photos of el Señor and His demandita, we take a seat in a front pew and wait for the initiation of el traslado. More people arrive and the pews behind us fill up. Among those who enter are men and women, including youth, wearing black T-shirts embroidered on the backs with Sr Calvario, Mayordomia 2017, Santa María Tomatlán. Members of the committee from the Pueblo and parish of St. Mary Tomatlán, they are evidently responsible for the transfer of El Señor to their community. They all enter a door to the office at the side of the sanctuary, filling the small room to its limits. They remain there for quite some time.

We wait. It is now approaching 5 PM. It is early December. The sun sets now a little before 6 PM. We get somewhat anxious wondering whether the procession will begin before the light drops. If it doesn't, we won't be able to get any good photos.

Finally, some minutes after 5 PM, the door to the office opens and members of the mayordomia enter the sanctuary. One member, a woman perhaps in her thirties, has a large, old-fashioned ledger book which she opens. Piled in front of her are various items. She checks off all the equipment needed for the transfer: slender metal poles, long, thick, polished wooden poles, small cushions for the bearers of the casket to cushion their shoulders. Then several members of the committee gather around the two caskets. There is a lot of activity.

|

| T-shirt identifying a member of the mayordomia, committee, from Santa María Tomatlán. Such identifying T-shirts (or sometimes, polo shirts) are standard dress for mayordomias. |

Finally, some minutes after 5 PM, the door to the office opens and members of the mayordomia enter the sanctuary. One member, a woman perhaps in her thirties, has a large, old-fashioned ledger book which she opens. Piled in front of her are various items. She checks off all the equipment needed for the transfer: slender metal poles, long, thick, polished wooden poles, small cushions for the bearers of the casket to cushion their shoulders. Then several members of the committee gather around the two caskets. There is a lot of activity.

|

| The caskets are covered with embroidered cloths. |

|

| Wooden poles are slid underneath the casket. |

The Procession to Santa Maria Tomatlán

|

| El Señor is carried from the Church of San Andrés. |

|

| The essential banda is ready to accompany the procession. We note that this one includes a number of women. Most often, bandas are all male. |

|

| Obligatory cohetes, rocket-style firecrackers, are shot off, announcing to the community that the procession is underway. |

|

| Avoiding the many stairs in front, the procession leaves via the side gate of the church, into the street leading toward traffic-filled Avenida Tláhuac. |

|

| Ancient and modern intersect. The procession enters Avenida Tláhuac. A train on Metro Line 12 passes above. |

|

| Archway at the entrance to Pueblo Santa María Tomatlán. Such archways are common at the entrances to original pueblos. |

|

| Procession of El Señor del Calvario arrives in Pueblo Santa María Tomatlán. |

|

| The faithful... |

|

| ...await. |

|

| The procession reaches a point in the street where two tables stand. They are covered with pink cloths. The caskets of El Señor and la demandita are lowered to the tables. |

The procession comes to two long tables, covered with pink cloths, and the two caskets are lowered carefully to them. Obviously, some kind of welcoming ritual is going to be carried out.

Time to Leave, Planning to Return

It is now 6 PM. The sun is down and the light is fast following it. It is time for us to leave and return to Coyoacán. We have already planned to come to Santa María Tomatlán in three days, on December 8, for the Feast of the Immaculate Conception, as we expect the parish will have a celebration of its patron saint, the Virgin Mary. So we anticipate that we will find El Señor del Calvario, and His demandita, in the church at that time.

Meeting El Señor del Calvario Once Again

We enter the now nearly empty sanctuary. To the right, halfway toward the altar, is a large opening, its arch decorated with pink and white gauze, the colors of San Andrés, St. Andrew, the parish from which El Señor came on Tuesday evening. Walking forward, we turn into the chapel.

It is not like any Catholic Church chapel we have seen in Mexico. It is not covered with Baroque gold gilt. Instead, the walls are covered with a mural that melds medieval with modern styles.

The walls and ceiling of the space are rounded, which, together with the warm tones of the mural, give it the feeling of a cave. That sensation and the mural remind us of where we started this Amble, not many blocks to the north, in la Capilla del Señor del Calvario, and the cave where He was found. El Señor, His Capilla and cave remain sacred to the people of Culhuacán and its neighbor, Tomatlán. With El Señor here in Santa María, newly arrived from San Andrés, we feel the completion of a cycle in the communal ritual which binds the many barrios of the two pueblos together.

El Señor del Calvario in Pueblo Santa María Tomatlán

Thursday morning, we follow our now routine path to Culhuacán and Tomatlán, taking first a taxi across Avenida Taxqueña then getting on Metro Line 12. This time we go past the San Andrés stop to the next one, get off and descend to Avenida Tláhuac. Walking a few blocks north, we turn onto the street that enters the pueblo. A short block farther on, we come alongside the church—a large, modern concrete structure with a gambrel, "Dutch-style" roof that reminds us of barns in the U.S. Northeast.

|

| A portada of plastic flowers covers the entrance— "Most pure Conception, protect your pueblo (people/village)" |

|

| Mass is being celebrated for the Immaculate Conception of the Virgin Mary. Her figure stands at the right, in front of the blue drape. |

Looking for a fiesta

Outside, we search the notices posted on the entrance walls for a schedule of fiesta events. There is only a handwritten sign announcing a series of special Masses today and next Tuesday, December 12, the Fiesta of the Virgin of Guadalupe, the Mother of Mexico.

Una señora, a matronly lady, is standing just outside the church door, beside a small table offering candles and other religious items. Clearly a representative of the congregation, she is dressed in an attractive green and white plaid wool coat (it is a brisk December morning), with matching, hand-knit wool scarf and cap. We approach her to inquire about the existence of a fiesta this weekend for the Immaculate Conception.

|

| Lady of the church and our informant. |

La señora informs us that there is no fiesta on this occasion, even though this is a church dedicated to the Immaculate Conception of Mary. She tells us that their big fiesta is held on Mary's Natividad, birthday, in early September. (At that time, we were at Church of Santa María Natividad Tepetlalzingo in Delegación Benito Juárez.) We tell her that we will put this on our schedule of fiestas, and, ojalá, God willing, be able to attend next year. She adds that the church also has a procession on Holy Friday of Semana Santa, Holy Week.

We tell her that, on Tuesday, we had followed the procession of El Señor del Calvario from the Church of San Andrés to the streets of Santa María, but, as it got dark, we didn´t follow Him to the Church. We ask if He is inside, since we can´t see His casket in the sanctuary. She says that, yes, he is in a chapel off to one side of the sanctuary. Mass is nearing its end with the passing of the peace among attendees. As we find this tradition meaningful, we shake hands with her and other parishioners standing inside the doorway. Our guide then enters to receive the Host.

A very small plaza across the street from the church catches our attention, since it is warmed by the late autumn sun shining into it. So we cross and sit on a bench, sunning ourselves while we wait for the end of Mass so we can enter the church.

|

| Sunny plazuela, little plaza. |

Soon, parishioners are leaving the church.

|

| Parishioners have brought their images of the Virgin Mary to be blessed at the Mass. |

Meeting El Señor del Calvario Once Again

It is not like any Catholic Church chapel we have seen in Mexico. It is not covered with Baroque gold gilt. Instead, the walls are covered with a mural that melds medieval with modern styles.

|

| El Señor del Calvario A crucified Christ hangs in the center of the mural. To the left is Moses with the Ten Commandments; to the right is the Apostle and Evangelist St. John. |

The walls and ceiling of the space are rounded, which, together with the warm tones of the mural, give it the feeling of a cave. That sensation and the mural remind us of where we started this Amble, not many blocks to the north, in la Capilla del Señor del Calvario, and the cave where He was found. El Señor, His Capilla and cave remain sacred to the people of Culhuacán and its neighbor, Tomatlán. With El Señor here in Santa María, newly arrived from San Andrés, we feel the completion of a cycle in the communal ritual which binds the many barrios of the two pueblos together.

|

| Delegaciones (Boroughs) of Mexico City Iztapalapa is the large, bright green one on the mid-east side. |

|

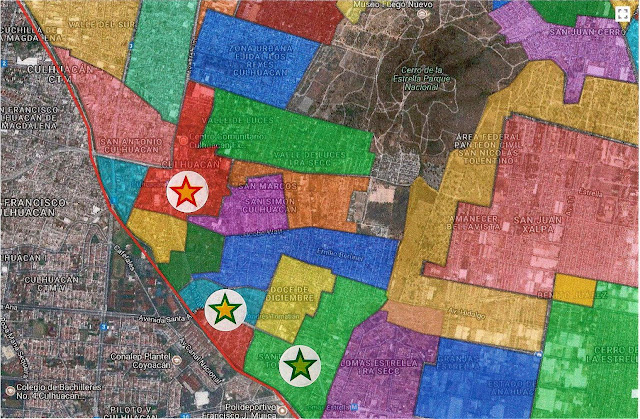

| Pueblos, Barrios and Colonias of Iztapalapa. Pueblos San Andrés and Santa María Tomatlán are marked by the green/yellow star. |

No comments:

Post a Comment