We learned, while attending his feast day celebaration, how this figure representing Christ in His Passion—His suffering during Semanta Santa, Holy Week—was seen as the source of a miracle some centuries ago, saving el pueblo, the people, of the various indigenous villages in what is now the borough of Coyoacán, from an epidemic.

Intertwining Communal Roots

So every summer, El Señor is carried forth from Tres Reyes to visit several of these other pueblos and barrios, where he is received by their respective saints, gives his blessing on the people and receives their adoration and thanks. He spends one to two weeks asentado, seated, in the church of each pueblo before moving on to the next. Hence, a series of bienvenidas and despedidas, welcomes and farewells to El Señor are festejados, celebrated, across Coyoacán from late May to early September.

It is a ritual that links together several of the borough's original villages in common belief, custom and history, hence maintaining the bonds of a shared identity that is muy arraigo, very rooted.

So on the next-to-the-last Sunday morning in May, we head back to Los Reyes for the Despedida to el Señor de la Misericordia as he begins his annual visitas to his larger flock. The parish fiesta schedule says la salida, the departure, of el Señor will be at 9:30 a.m. I arrive at the atrio of the church at about 9:15.

El Señor and his entourage are ready to go. Although Mexicans, themselves, will acknowledge that they are not punctual—i.e., governed by the clocks of the industrialized world except when they work in the setting of a modern organization—we see that these ceremonies of complementary farewell and welcome are carried out on time.

|

| El Señor de la Misericordia, the Lord of Compassion, ready for his departure from Los Reyes |

Ancient Rituals: The Royal Treatment

Flowers:

El Señor is dressed, this time, in a bright orange, royal cloak and surrounded on his throne by a lavish arrangement of roses and other fresh flowers. We recall the elaborate portada of flowers that covered the church's facade in April, when we first encounted El Señor. The pueblo of Tres Reyes certainly loves an abundance of flowers for its fiestas!

We have read, in la Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, 'The General History of the Things of New Spain'—compiled by the Franciscan friar, Bernardino de Sahagún from indigenous, Nahuatl-speaking interlocutors in the mid-1500s—that flowers were one of many important components of indigenous rituals. That custom clearly hasn't changed.

We have read, in la Historia General de las Cosas de Nueva España, 'The General History of the Things of New Spain'—compiled by the Franciscan friar, Bernardino de Sahagún from indigenous, Nahuatl-speaking interlocutors in the mid-1500s—that flowers were one of many important components of indigenous rituals. That custom clearly hasn't changed.

|

| Beloved Señor, his hands tied in his persecution by Roman soldiers, bearing a golden scepter that is a stalk of corn, the primal source of life in Mexico. |

Very quickly, with focused purpose, members of the parish confradía, brotherhood organization, raise the heavy palanquin to their shoulders and start off.

We recall Hernán Cortés' description of the arrival of Moctezuma to meet him on the causeway connecting Tenochtitlan with Iztapalapa in 1519.

|

| Moctezuma II (the Younger) meets Hernán Cortés on the causeway to Iztapalapa, Nov. 8, 1519 Tile mural on wall of Jesús Nazareno Church, on Pino Suárez Ave., in Centro Historico, reproduced from an 17th or 18th century oil painting. |

Carried aloft:

Evidently, such palanquin were used quite universally to demonstrate a person's high status. The word palanquin is Portugese, adopted from the Sanskrit name of the vehicle carrying Indian princes, encountered when Portuguese mariners arrived in India in the 15th century.

We also remember how Moctezuma's feet were not allowed to touch the bare ground. Carpets were placed below them. He could also not be touched, as he was the sacred incarnation of the god Huitzilopochtli.

Music: La Banda

The procession is lead by a banda, a brass band, reminiscent of bands in Europe, with their brass and woodwind instruments, their music always grounded in the rhythm of a tuba and accompanying drums.

Sahagún also tells us that indigenous processions with idols representing their gods were accompanied by the music of drums, wooden flutes and conch shells.

|

| El Señor de la Misericordia is carried through the narrow streets of Pueblo Tres Reyes |

Visiting Old Neighbors

Today, El Señor and the feligreses, parishoners, are headed for the Pueblo de Xoco (Sho-ko) and its church of San Sebastián the Martyr, which is actually some three kilometers, about two miles, to the north as the crow flies. Today Xoco is in Delegación Benito Juárez, across Río Churubusco, formerly one of the main rivers feeding Lake Texcoco from the western mountains and later supplying the Royal Canal, which nowadays is the National Canal.

In modern Mexico City, an expressway of the same name covers the encased river. Evidently, Xoco was part of a group of related pueblos in the area, most of which are now in Coyoacán. The river became the official boundary only in 1928. Once again, tradition overrides officialdom.

In modern Mexico City, an expressway of the same name covers the encased river. Evidently, Xoco was part of a group of related pueblos in the area, most of which are now in Coyoacán. The river became the official boundary only in 1928. Once again, tradition overrides officialdom.

|

| The confradía frequently has to stop and set down the heavy palanquin and its sacred, royal occupant. |

As the members of the confradía frequently have to stop and set down their passenger in order to rest from the weight, we have many opportunities to take note, and photos, of the feligreses participating in the procession. As we walk through the narrow streets that characterize a barrio, more people join in.

El Pueblo, The People

Hasta la próxima vez, Until the next time

We follow the procession as it circles through the calles, streets, of Tres Reyes. When we reach a main thoroughfare and it starts off toward Xoco, we part ways. Three kilometers—two miles or more, given the winding streets of Coyoacán—is a bit too much for us.

But, thankfully, the organizers of the procession have handed out a calendar listing the sequence of El Señor's visits, with the date, time and location for each Sunday encounter where one host pueblo or barrio will deliver him to the next. So we are provided with a map and timetable for our continuing ambles through the pueblos originarios of Coyoacán.

El Señor will be our guide, introducing us to each one. Gracias al Señor de la Misericordia and the at-least 500-year-old communal tradition he embodies.

|

| El Señor de la Misericordia on his way to Pueblo Xoco |

|

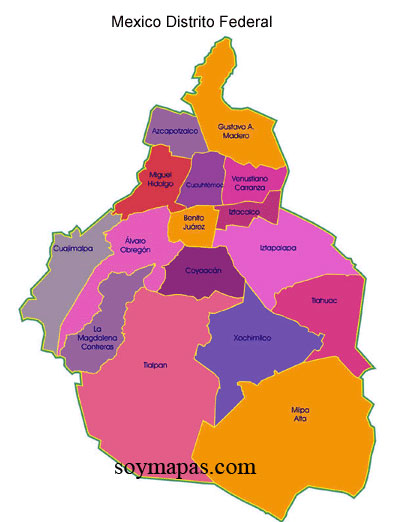

| Pueblo Tres Santos Reyes - lower star Pueblo Xoco - upper star |