Early on in our ambles around Mexico City, when we began asking ourselves what sense might be made of its battiburillo, hodgepodge, of styles, we noticed some buildings that stood out for their ornate style in contrast to their often undistinguished surroundings. Fanciful combinations of richly framed, often arched windows and doorways and a peculiar style of column (spirals instead of Neoclassic Greek), the buildings were neither Spanish Colonial nor Neoclassic, but nor were they yet modern. They appeared to be from the first half of the 20th century.

As we undertook a more systematic exploration of the colonias, neighborhoods, begun at the end of the Porfiriato (1876-1911) and, particularly, those developed mostly after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), we encountered many more of these edifices, obviously homes of the upper-middle class. With some exploration in Wikipedia, we learned that they are Spanish Colonial Revival or, more specifically, California Colonial.

|

| Mystery building in Colonia Villa de Cortés on the Calzada de Tlapan, Delegación Benito Juárez |

As we undertook a more systematic exploration of the colonias, neighborhoods, begun at the end of the Porfiriato (1876-1911) and, particularly, those developed mostly after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920), we encountered many more of these edifices, obviously homes of the upper-middle class. With some exploration in Wikipedia, we learned that they are Spanish Colonial Revival or, more specifically, California Colonial.

|

| Colonia Cuauhtémoc |

|

| El Parián Market in Roma Norte |

|

| Colonina Condesa |

|

| Colonia Condesa |

But where did this style come from, in particular, these non-Classic, even counter-Classic spiral columns? With further investigation via our faithful Wikipedia, we found their history goes back more than a millenia and a half.

Emperor Constantine, King Solomon and St. Peters

In the 4th century, Constantine the Great, the first self-proclaimed Christian emperor, brought back to Rome a set of columns from the Eastern part of the Roman Empire. The columns were to be used in construction of the original St. Peter's Basilica.

|

| Painting from Raphael's workshop, a donation of Constantine, shows these columns in their original location. Early 16th century Wikipedia |

According to tradition, these columns came from the "Temple of Solomon", even though Solomon's Temple, the First Jewish Temple, built in the 10th century BCE, was destroyed in 586 BCE, and the Second Temple was destroyed by the Romans in 70 CE.

Constantine is recorded as having brought the columns back from Greece. Documented as cut from Greek marble, they are thought to have been made in the 2nd century CE. Nonetheless, they became known as "Solomonic".

|

| Original "Solomonic columns" of Emperor Constantine Wikipedia |

Some of these columns remained on the altar of the original St. Peter's Basilica until the structure was torn down in the 16th century. Although removed from the altar, eight of these columns remain part of the structure of today's St. Peter's Basilica.

Baroque Epoch

When Gian Lorenzo Bernini was commissioned by Pope Urban VIII in 1629 to complete the interior of St. Peter's, he chose the ancient Solomonic columns as his model for the colossal bronze Baldacchino, which was finished in 1633 (Wikipedia). With their dynamic twists, they, in turn, became the models for other Baroque architecture, including in Catholic Spain.

|

| Bernini's Baldacchino in St. Peter's Basilica Wikipedia |

|

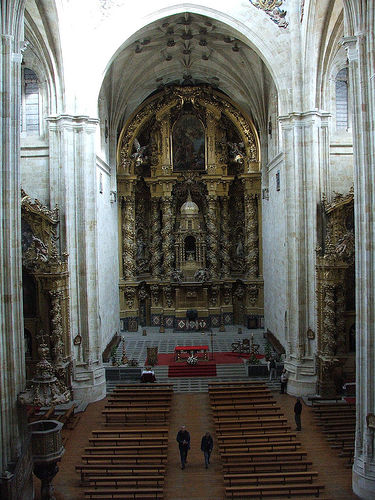

| Altar of the Church of St. Stephen, Salamanca, with Solomonic columns, by José Benito de Churriguera Wikipedia |

The style spread from Spain to the Spanish colonies in the Americas, where the salomónica column was often used in churches as a key element of the Churrigueresque style.

|

| Cathedral of Zacatecas Early 18th century Wikipedia |

At this point, my mental light bulb went on.

I had seen these spiral columns before, in the city of Puebla, famous for its Baroque epoch churches.

|

| Solomonic columns on Baroque church in City of Puebla |

|

| Church of St. María Tonantzintla, indigenous village outside Puebla |

|

Church of Santo Domingo

City of Puebla

Chapels built late 17th century

|

This led me to wonder whether any churches with salomónica columns existed among Mexico City's innumerable Spanish Colonial churches. I couldn't recall any, but then, I have to admit, Baroque churches are not exactly to my taste. Nevertheless, I didn't have to look far.

|

| Metropolitan Tabernacle, attached to Metropolitan Catherdral in Mexico City, is full Churrigueresque Baroque, but without Solomonic columns Built mid-18th century Architect, Lorenzo Rodriguez |

Right next door, on the main facade of the Cathedral itself.....

|

| Solomonic columns above side portal of Metropolitan Cathedral in Mexico City. Facade finished at end of 18th century in Neoclassic style by Manuel Tolsá. |

|

| Neoclassic elememts of Cathedral facade |

Baroque Ornateness Replaced by Neoclassic Formalism

In the latter part of the 18th century, the Baroque style was replaced by the straightforward lines of Neoclassicism. With its models in classic Greek and Roman architecture, Neoclassicism is seen to typify the Enlightenment value of reason over emotion. Two sections of the southern, main facade of Mexico City's Metropolitan Cathedral—constructed half a century apart—exemplify this shift: the Churrigueresque Tabernacle and Neoclassic main facade.

Manuel Tolsá, a Spanish architect who came to Mexico in the latter part of the 18th century, embodied this transition. In addition to completing the front of the Metropolitan Cathedral, he designed many Neoclassic buildings right up to the time of the Mexican War for Independence (1810-20). Neoclassicism continued to be the dominant architectural aesthetic in Mexico through the 19th century. Moreover, as we have seen in the public buildings and homes of the wealthy during the Porfiriato, it continued into the early 20th century.

|

| Gallician Center, Colonia Roma, built in Neoclassic style, 1930's |

So we ask ourselves: how did a more elaborate Baroque flavor, with non-"classic" elements, including Solomonic columns originating in the eastern Mediterranean nearly 2,000 years ago, reassert itself in the early 20th century and end up back in Mexico City?

Romanticism and Return of the Dramatic

Mexico's Moorish Pavilion for the New Orleans and St. Louis Expositions is another example.

Spanish Colonial Revival Architecture and San Diego Panama-California Exposition

Near the end of the 19th century, in Florida and California, with their Spanish heritages and warm climates, architectural revivals developed that reflected their history. In Florida, hotels for winter visitors were built in what was known as Mediterranean Revival style. In parallel, Mission Revival, based on California's original Franciscan missions, also developed.

This aesthetic current coincided with the Spanish-American War (1898), which led to Cuba becoming a de facto U.S. protectorate, and construction of the Panama Canal (1904-1914). Both events brought increased U.S. interest and involvement in Latin America. The Canal's impending opening led the two formerly Spanish/Mexican cities of San Diego and San Francisco to decide to hold Expositions of the type popular in that era. Both cities saw great economic opportunities in connecting the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans for ocean trade.

San Francisco,with a population nearly ten times larger than its southern sister, was ultimately supported by politicians in California and Washington, D.C., and it ended up hosting the official Panama–Pacific International Exposition. Nevertheless, San Diego leaders decided to forge ahead with their own Panama-California Exposition. Thus, it is not surprising that its architects, Bertram Goodhue, and his partner, Carleton Winslow, both from New York, decided on a design based on ornate Spanish and Mexican Baroque Churrigueresque decoration, with influences from Moorish Revival architecture.

Goodhue had already experimented with Spanish Baroque in Havana and in Panama. Among his specific stylistic sources for the San Diego Exposition were the Mexico City Metropolitan Cathedral and the Cathedral of Our Lady of the Assumption in Oaxaca. Goodhue's and Winslow's designs combine Baroque ornateness with plain, calming stucco walls. They included Solomonic columns.

|

| California Building San Diego Exposition Wikipedia |

We don't know who brought the style, now known as California Colonial, back to Mexico City after the Revolution. Perhaps it was even a U.S. architect, like Lewis Lamm of Roma Norte fame, or one of the architects involved in the U.S.-owned Mexico City Improvement Company that developed what was named Colonia Americana (now Colonia Benito Juárez). Be that as it may, the California version of Spanish Colonial Revival, with its salomónica columns, is alive and well in Mexico City.

|

| California Colonial, Colonia Roma Sur |

No comments:

Post a Comment