Carmelites in Mexico City

To accomplish this huge task, Cortés first relied on Franciscan monks. They were soon joined by Domincans, Augustinans and members of other religious orders. Among the later arrivals were the Discalced or Barefoot Carmelites.

We have visited and written about the Carmelites' first convent, the Convent and Church of San Ángel, begun in 1597 and now located in the colonia of the same name in Delegación Álvaro Obregón. We have also visited their Church and Convent of San Joaquín, now in Delegación Miguel Hidalgo, built a hundred years later, in 1689, more modest in size than San Ángel but remarkable for its medieval architectural simplicity.

A third Carmelite convent still stands within Mexico City. But, unlike San Ángel and San Joaquín, it does not sit in the midst of urban modernity and congestion. Instead, it sits in a "desert". But this "desert" is not arid and barren. It is a lush, shady forest of towering conifers in mountains that rise as high as as 3,800 meters, 12,400 feet in altitude, 5,000 feet above the Valley, on the west side of the city, in the Delegación Cuajimalpa. Comprising some 4,600 acres, it is now a national park, Desierto de los Leones, Desert of the Lions.

Convent in the Desert of the Lions

|

| Desierto de los Leones |

Convento del Desierto de Nuestra Señora del Carmen de los Montes de Santa Fe, Convent of the Desert of Our Lady of Carmen of the Mountains of the Holy Faith is now officially called Ex-Convento del Desierto de los Leones, Ex-convent of the Desert of the Lions. Built by the Carmelites shortly after San Ángel, at the beginning of the 17th century, it sits at an altitude of 9,700 feet, nearly 3,000 feet above the Valley floor.

As for why the forest came to be called Desierto de los Leones, there are two stories, one romantic, the other pragmatic. The first is that there were mountain lions in the woods, making it a place of risk. The other is that a Spanish family named León had been granted the land by the king, and they donated it to the Carmelites, perhaps to gain holy indulgences for their sins and thus save themselves from having to pay for them after death with time in Purgatory.

As for why the forest came to be called Desierto de los Leones, there are two stories, one romantic, the other pragmatic. The first is that there were mountain lions in the woods, making it a place of risk. The other is that a Spanish family named León had been granted the land by the king, and they donated it to the Carmelites, perhaps to gain holy indulgences for their sins and thus save themselves from having to pay for them after death with time in Purgatory.

|

| Convento del Desierto de Nuestra Señora del Carmen de los Montes de Santa Fe |

What does it mean that this Carmelite convent in an evergreen forest is "in the desert". And why was it built so far from the colonial city that sat in the middle of Lake Texcoco and the original indigenous villages that surrrounded the Lakes? Those villages were the objects of the Spiritual Conquest, the work, the vocation, of the religious orders, including the Carmelites. San Ángel and San Joaquín were established in two key villages, Tenanitla and Tlacopan on the west shore of the Lake, in order to carry out the conversion of los indios.

The convent still remains quite apart from the vastly larger modern city that now occupies the entire Valley floor and is determinedly climbing the mountain slopes. Reachable only by car along one of two narrow roads winding up the mountains, it still sits in the midst of a tranquil world far apart from the bullicio, hubbub, of contemporary Mexico City.

Answering these questions requires us to go back in time three hundred years before the Carmelites arrived in Nueva España and from Spain to the other end of the Mediterranean, to the time of the Crusades and the Holy Land.

The Carmelites: From the Prophet Elijah to the Holy Land Crusades to Nueva España

The Carmelite religious order originated in the early 13th century, during the era of the Crusades (11th to 13th centuries). The Order was formed by lay European pilgrims on Mt. Carmel in the Holy Land. They chose Mount Carmel because it was the site of various miraculous acts of the prophet Elijah. Carmelite tradition holds that a community of Jewish hermits continued to live at the site from the time of Elijah (9th century BCE) until the founding of their order there 2,000 years later. There are historical records of a group of ascetic Essenes living on the mountain in the second and first centuries BCE.

Carmelite monks followed this ascetic tradition, leading strict, self-disciplined lives as recluses, hermits, their lives devoted to solitary prayer, perpetual silence and penitential mortification of the body to overcome temptation to sin and develop a humility of spirit.

|

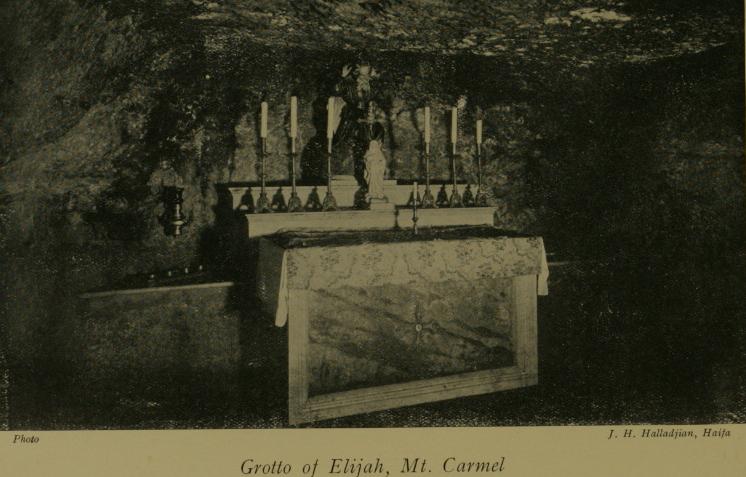

| Grotto of Elijah, on Mount Carmel in the Holy Land Wikipedia |

In the latter part of the 13th century, members of the order were forced to returned to Europe because of numeous conflicts between Crusader States that had been created in the eastern Mediterranean and resurgent Muslim forces that culminated in the formation of the Ottoman Empire at the end of that century.

Over the next three hundred years, a combination of the prevailing political and social conditions in Europe—the Hundred Years' War and the Black Plague, with their untold numbers of deaths and economic devastation, and the rise of the Renaissance and Humanism—adversely affected the Order. There was a general decline in religious fervor. The strict ascetic Rule governing the order was "mitigated" several times. Consequently, the Carmelites bore less and less resemblance to the first hermits of Mount Carmel.

Counter-Reformation and Carmelite Renewal

In the 1500s, the Roman Catholic Church was challenged by the Protestant Reformation. As part of the Counter-Reformation there were many initiatives to purify and renew the Catholic Church. Among those feeling the call to reform and renewal was a Spanish nun, later to become St. Teresa of Ávila, who sought to return the Carmelites to their Primitive Rule. In 1562, with a group of fellow nuns, she established a small convent in the city of Ávila, Spain. The Rule of the order contained exacting prescriptions for a life of continual prayer, with strict enclosure within the convent, sustained by the asceticism of solitude, manual labor, perpetual abstinence, fasting and charity.

A monk, who was to become St. John of the Cross, established the first men's convent of Discalced Carmelite friars in Duruelo, Spain in 1568. Nearly thirty years later, in 1597, members of the order arrived in Nueva España and began construction of their first convent, San Ángel.

|

| St. John of the Cross, Founder of the Discalced Carmelites Painting by Francisco Zubarán, 1656 Wikipedia |

Convent in a Desert of Mountains

Just ten years later, the Carmelites began construction of their convent "in the desert". While the mountains around the Valley of Mexico were an environment radically different from Mt. Carmel in the Holy Land, they provided the characteristic of a desert essential to the Carmelite discipline. As a wilderness set apart from human community, they provided the isolation essential to an eremitical life of solitude and prayer, "far from the madding crowd's ignoble strife" (Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard, Thomas Gray).

While the mission of the Carmelites in the New World of Nueva España, like that of all the other religious orders, was the conversion and education of los indios, which was an intensely communal and interactive process, the Convent of the Desert gave them a retreat from that world where they could return to and be nourished by the roots of their four-hundred-year-old spiritual heritage and practice. It made possible the combination of fullfilling a vocation in the world of people and eremitical withdrawal to solitude, silence and self-purification.

|

| Gated path leads through the forest to a chapel for prayer |

|

| Chapel of the Secrets Monks could pray aloud together here, but had to face the walls to avoid eye contact. |

Construction of the convent began in January of 1606. It was designed by Friar Andrés de San Miguel, who also designed the Convent of San Ángel, and whose own interesting story of salvation from a ship wreak we came upon in our research on that convent. By 1722, because of the wet climate of the mountains, the original Desierto convent had greatly deteriorated, so it was demolished and a new convent, the one still standing, was built in its place.

Only four monks lived in the Convent year-round. Other brothers would come from San Ángel, and other convents the order built throughout Nueva España and spend time in spiritual retreat. Over time, a dozen hemitages, small, single-room quarters, were built in the woods around the grounds to which monks could retreat for fasting, solitary prayer and meditation. These were used primarily during the holy seasons of Advent and Lent, forty-day periods modeled on Jesus' forty days in the wilderness before he began his preaching mission.

|

| Gateway to a hermitage |

|

| Hospedería patio Guests' patio Rooms around the patio were for secular guests, well-to-do Spanish men. They were not allowed to enter the convent proper. No women were allowed. Neither were indios, indigenous, or mestizos, mixed-blood persons. |

|

| Convent garden, where vegetables and fruits would have been grown. |

|

| Convent garden |

Modern-day Urban Retreat

Some time after Independence from Spain was won in 1821, the convent was abandoned. In 1876, the forest around it was declared the first forest preserve in Mexico, primarily to protect the springs and streams that provide drinking water to Mexico City. In 1917, at the end of the Mexican Revolution, President Venustiano Carranza declared it the first National Park.

The Desert of the Lions is no longer a retreat for ascetic religious self-discipline. But it does provide secular respite for city residents and other Mexicans, with hiking and biking trails and cool, shady, quiet places to relax. Restaurantes campestres, open-air restaurants, provide traditional Mexican meals under the towering, cathedral-like evergreen trees. There are also tables and barbecue pits for family picnics.

|

| Cuajimalpa is the long, narrow, magenta-colored delegación on the west side of Mexico City |

|

| Cuajilmapa Ex-Convento Desierto de los Leones is in the dark green, forested area of the National Park Desierto de los Leones Two narrow roads (white lines) wind from lower urban areas to the Convent |

No comments:

Post a Comment