Es fácil traducir esta página en español: vaya a la columna a la derecha. En la parte más alta hay una ventana etiquetada "Translate". Desplace la flecha abajo hasta encuentra "Spanish". Click en ese y inmediatamente todo el texto estará traducido en español por Google. Con certeza, habrá errores, pero creemos qué el sentido se quede bastante claro.We started Mexico City Ambles exploring the City's physical and historic Center, Colonial Centro Histórico. Then we moved on to explore the expansion of the City, beginning with the transition from Spanish colony to Mexican Independence (1821) and passing through the 19th century, with its vestiges of the volatile epoch of the Reform (1857-1876), the prosperity of the Porfiriato (1876-1911), with its initiation of many European-style, upper-class colonias, and arriving, lastly, at the Revolution (1911-1917), with its abundance of public art produced by the Mural Movement.

Having come up almost to contemporary times, our interest took a turn back to the beginnings of Mexico City and its development from the original Mexica city of Tenochititlan and the many altepetls, city-states, and pueblos that existed around Lake Texcoco. We discovered and explored the four original barrios or parcialidades of San Juan Tenochtitlan that still exist, almost hidden, in Centro Histórico. Now we find ourselves ready to return to our home base of Coyoacán and begin to explore its pueblos originarios.

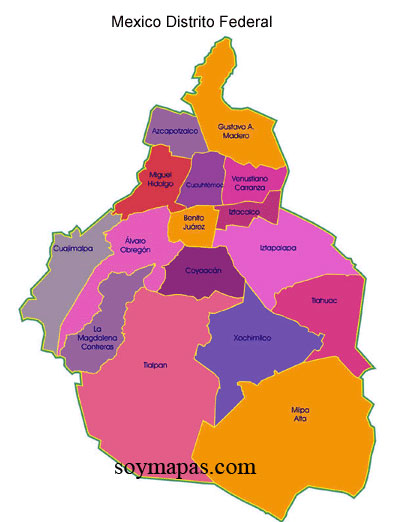

We live in Colonia Parque San Andrés, St. Andrew's Park, an upper-middle-class, residential neighborhood of modern private homes, townhouse complexes and small apartment buildings, in Delegación Coyoacán, the borough of Coyoacán, Place of the Coyotes, about five miles south of the Zócalo in Centro Histórico, Delegación Cuauhtémoc.

|

| Coyoacán is the deep purple, trapezoid-shaped delegación, in the virtual geographic center of the City just south of Benito Juárez, which is south of Cuauhtémoc, the location of Centro Histórico. |

1,800-Year-Old Village

|

| Fountain of the Coyotes, in Jardin de los Centenarios, Garden of the Centenarians, Villa Coyoacán |

Before the arrival of the Spanish in 1519, the historic center of Coyoacán, named Villa Coyoacán by Hernán Cortés, about a mile west of Parque San Andrés, was an indigenous village with a long and complex history.

Archeological investigations have found remains of an initial settlement from around the year 200 CE. It is thought that before that time, Lake Xochimilco and Texcoco were larger and water covered this part of the valley. The settlement was a short distance east of the Villa in the location of what is now the Chapel of the Concepcion, built on Cortés' orders in 1521. It is now el Barrio Concepción. It is likely it was built by the first people to establish agriculturally-based settlements in the Valley, the Otomí, who had domesticated the cultivation of corn in the Balza River Valley just over the mountains to the east (now in the State of Puebla). Hunter-gatherer tribes had been in the Valley since at least 9,000 years ago.

In the 7th century CE. this settlement was considerably enlarged, likely having been taken over by Tolteca, the earliest Nahuatl-speaking tribe to enter the Valley they called Anahuac. Earlier in that century, they had first taken over a pre-existing village on the peninsula separating Lake Xochimilco, to the south, from Lake Texcoco to the north. They named their settlement Culhuacán, The Place of the Old Ones. They subsequently took over the settlement in Concepcion, across the narrow channel connecting the two lakes, giving them control of that waterway. For five hundred years, they maintained the settlement. In the mid 12th century, this site was abandoned for unknown reasons, which is curious, as the Toltecas, based in Culhuacán remained a major power in the valley until the 14th century.

Meanwhile, around the year 1000 CE, another Nahuatl-speaking tribe, the Tepaneca, entered the Valley and, over time, took over the Otomí villages on the west side of Lake Texcoco, establishing their main city at Atzcapotzalco (now within the delegación of that name at the northern end of the City). By 1350, they had pushed south into what had been Tolteca territory. West of the abandoned la Concepción site, they built a larger village where the present Villa Coyoacán is located. It is possible they gave it the Nahuatl name of Coyoacán.

Information from an article, Evidencias arqueologícas en el Centro de Coyoacán, Archeological Evidence in the Center of Coyoacán, in the magazine Arqueología mexicana, issue of Sept.Oct. 2014, pp. 43-48.The Tepanecas of Atzcapotzalco and the Toltecas of Culhaucán, based on opposite sides of Lake Texcoco, were to remain competing powers until another Nahuatl-speaking tribe entered the Valley in 1225 and, over a two-hundred-year period, were eventually able to gain sufficient strength to challenge both.

These were the Mexica (aka Azteca), the last of the Nahuatl speaking tribes to arrive in the Valley. Over a period of one hundred years, they attempted alliances with various of the existing altepetls around the five lakes, including with the Toltecas. For a couple of decades at the end of the 13th century, they were able to maintain their own altepetl on the hill called Chapultepec, Then they were forced to become subjects, first, briefly, of the Tolteca of Culhuacán and then of the Tepaneca of Atzcapotzalco. The Tepaneca allowed them to finally obtained their own land, a set of islands in Lake Texcoco. There they founded their own altepetl, Tenochtitlan in 1325. As subjects of the Tepaneca, they helped them conquer the Toltecas of Culhuacán in 1385.

For a more detaiedl history of the entrance of the Mexica to the Valley and their two-hundred-year-long, circuitous rise to power, see our post: San Juanico Nextipac: Stepping Stone to History.Over the next forty years, the Mexica became powerful enough that, along with allies from other altepetls (called the Triple Alliance), in 1428 they overthrew the Tepanecas and became lords of the entire Valley. Coyoacán came under their control. They expanded the city to an even greater size, as their main base of power and trade in the southwest of the Valley.

|

| Scoring ring from ball court, unearthed next to Church of San Juan Bautista, Villa Coyoacán |

|

| Major villages around the five lakes of the Valley at the time the Spanish arrived in 1519 |

Transformation into a Spanish Village

As one of the main entrances to Tenochtitlan, via the causeway, Coyoacán held a strategic position. On the Noche Triste, Night of Sadness June 30, 1520, after the Spanish massacred Mexica priests and leaders and their tlatoani, ruler, Moctezuma was subsequently killed, Cortés and his troops had to flee from Tenochtitlan west to Tlacopan. They returned to the Valley in the spring of 1521, and Cortés gained the support of Coyoacán's Tepanec tlatoani to give him access to the causeway in order to attack the Mexica city.

After Cortés conquered the city in August 1521, he then set up his headquarters in what he named Villa Coyoacán while the Mexica city was rebuilt into the Ciudad de México. As he had done upon landing on the mainland, establishing la Villa Rica de la Vera Cruz and having his troops elect him the equivalent of mayor, in naming Coyoacán a "Villa", he was declaring it officially to be a Spanish village according to Spanish law, with rights to internal self-government by its Spanish residents (somewhat like an official village in the U.S.) and to direct appeal to the king. This was his way of claiming independence from the governor of Cuba, who had charged him with an exploration of the mainland coast, not to land and attempt to conquer it. He thereupon bypassed the governor of Cuba and communicated directly with King Charles, reporting his victories and seeking royal approval.

Because of Cortés choice of Coyoacán as his initial official seat of power, the earliest Spanish Colonial government buildings and churches in Mexico City and Mexico are here. (The earliest Spanish settlement on the continent had been established in 1510 in Panama).

Coyoacán after the Spanish Conquest

(here spelled Coyohuacán) and surrounding settlements with original indigenous names, and convents and churches established by Franciscans and Dominicans.

The dashed blue line to the east shows the location of the shore of Lake Texcoco in the 16th century.

The locations of original indigenous settlements and roadways (in red)

are overlaid on the streets of modern Coyoacán, (in white).

The north-south roadway at far right was the causeway that crossed Lake Texcoco. This map is the first we have seen giving original names we have not previously found of some of the indigenous pueblos, many of which are no longer used.

From La evangelización del área coyoacanense en el siglo XVI,

The Evangelization of the Area of Coyoacán in the 16th Century, by Jaime Abundis from Arqueología mexicana, Sept.-Oct 2014 issue, |

|

| Ayuntamiento, "City Hall"—initially constructed by Hernán Cortés in 1521—is the first Spanish government building in Mexico. |

|

| Chapel of the Immaculate Conception, "La Conchita", "The Little Shell". Hernán Cortés had the first Catholic chapel erected here in 1521, on an indigenous temple site, making it one of the first Catholic churches in the continental Americas. Subsequently, it was assigned to the Franciscans. The structure was rebuilt in the late 17th century with a Baroque facade. Recently restored. |

|

| Church of San Juan Bautista, St. John the Baptist, Villa Coyoacán. Original church built in the mid-16th century by the Dominicans. |

|

| Chapel of Santa Catarina Site of original building erected by Dominicans in 16th century, the current chapel was erected around 1650. Originally, it was an indigenous settlement called Omac. |

Transition to Modernity

Frida Kahlo's family lived in the neo-colonial Casa Azul, Blue House, in Del Carmen. The house in which Leon Trotsky was assassinated is a couple of blocks north.

|

| Garden of Frida Kahlo's Caza Azul, Blue House. |

The delegación was created in 1928, when the Federal District was divided into sixteen boroughs. However, the urban sprawl of Mexico City did not reach the borough until the mid-20th century, turning farms and the former lakebed into developed areas (Wikipedia).

Today, the colonias of Villa Coyoacán, Concepción, Santa Catrina and Del Carmen retain much of their Spanish Colonial and early 20th-century Neo-colonial architecture and constitute a charming, upscale, tourist-filled neighborhood where chilangos (city residents) and tourists take a weekend break from the bullicio, the hustle and bustle, of the modern city. We frequently have Sunday brunch in one of its many restaurants.

|

| Francisco Sosa Street, lined with Colonial homes. The design on the facade is Spanish Moorish. The street was originally the indigenous pathway west to the village of Tenantitla, which is now Spanish Colonial San Ángel. |

Many Coyoacáns

There are, however, other Coyoacáns. The Delegación encompasses twenty square miles, almost the size of Manhattan. It is divided into ninety-seven colonias of widely varying sizes. The Colonial-period and Porfiriato neighborhoods occupy only the northwest corner.

The Calzada de Tlalpan, which crossed Lake Texcoco, touched land in what is now Barrio San Diego Churubusco (light blue ). The Spanish extended it south to the villages of Tlalpan and Xochimilco. It now divides the Delegación in half. Avenida Miguel Ángel de Quevedo and its extension on the east side of Calzada Tlalpan, Calzada Taxqueña, runs west to east.

- East of the Calzada de Tlalpan was originally the channel connecting Lake Texcoco with Lake Xochimilco to the south. The former lakebed is now filled with late 20th-century housing and commercial shopping centers (think Home Depot and Walmart), which have replaced the indigenous chinampas ("floating gardens") of the lake and, after the Spanish drained the lake, Spanish haciendas (large estates for raising cattle or wheat).

- The Far Eastern side of the Delegación was originally part of the peninsula of Iztapalapa and site of Culhuacán. It is now Pueblo San Francisco Culhuacan, divided into four barrios, and historically and still functionally connected to what is now Pueblo Culhuacan in Delegación Iztapalapa. We will explore both Culhuacans when we move on to Iztapalapa.

- The Southwest area was mostly scantily inhabited lava beds, pedregal (stony ground), created when, between 150 and 200 CE, the volcano Xitle buried the Otomi city of Cuicuilco. Dating from about 800 BCE, it was probably the earliest urban center in the Valley of Mexico. It was likely inhabited by Otomí people, the earliest known tribe to establish settlements based on corn agriculture in the Valley. The residents fled to the site that was to become Culhuacan and to Teotihuacan, the major Mesoamerican city in the north of the Valley. Part of the pedregal is now the site of the Ciudad Universitaria, University City, of the National Autonomous University of Mexico, UNAM. The rest is composed of two colonias, Ajusco and Santo Domingo, that were established by squatters in the 1960s and 70s when the city's population exploded from migrants coming from rural parts of Mexico. (See our page: How Mexico City Grew From and Island Into a Metropolis.)

|

| Cuicuilco's Round "Pyramid" |

Pueblos originarios

Running along the west side of the Calzada, north and south of Avenida Miguel Ángel de Quevedo (named after a mid-20th century architect and promoter of urban reforestation), and along the south side of Miguel Ángel, opposite Villa Coyoacán and its companion colonias, is yet another Coyoacán, a cluster of pueblos and barrios that were indigenous settlements long before the Spanish arrived.

Along the Calzada, north of Miguel Ángel, they are:

- Barrio San Diego Churubusco (its indigenous name was Huitzilolpocho, originally an island under the control of Culhuacán, not Coyoacán),

- Barrio San Mateo Churubusco (the southern part of Huitzilpochoco);

- Barrio San Lucas (its indigenous name was Quiahuac)

West to east along Miguel Ángel

- Barrio de San Francisco (its indigenous name was Hueytitlan);

- Barrio de Niño Jesús (its indigenous name was Tehuitzco);

- Pueblo de los Santos Reyes (its indigenous name was Hueytitlac).

Along the Calzada, south of Miguel Ángel

- Pueblo de la Candelaria (its indigenous name seems to be unclear. We have read that it was called Tlanalapa or Tlanancleca; however, the rear side of its entrance arch says it was called Chinampan (area of chinampas, man-made islands in the lake) Macuitlapilco.

- Pueblo de San Pablo Tepetlapa;

- Pueblo de Santa Ursula Coapa.

These barrios and pueblos are among the one hundred and fifty pueblos originarios, original villages recognized by the Mexico City government. As such, they are living continuations of the Spiritual Conquest carried out by the Franciscans and members of other monastic orders. It is to them that we direct our next series of ambles.

See also:

See also:

Mexico City's Original Villages: Introduction - Landmarks of the Spiritual Conquest

The Spiritual Conquest: The Franciscans - Where It All Began

Coyoacán: Pueblo of Tres Santos Reyes and the Lord of Compassion

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Goes Visiting

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Visits Barrios San Lucas and Niño Jesús, the Child Jesus

Coyoacán: Pueblo Candelaria Welcomes the Lord of Compassion

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Travels from San Pablo Tepetlapa to Santa Úrsula Coapa

Coyoacán: The Lord of Compassion Returns Home to Pueblo Tres Santos Reyes

Coyoacán: San Mateo Churubusco - Identity Via Church and Market

No comments:

Post a Comment