We have been following the trail of the Mexican Muralists from their gestation in the Academy of San Carlos, their first realizations in the College of San Ildefonso, at the Secretariat of Public Education and Bellas Artes and other spaces in Centro Histórico then on to other locations in the city. We came face to face with David Alfaro Siqueiros's last, grand work at the Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum in the delegación, borough, Benito Juárez and his work, as well as that of Juan O'Gorman and others at the National University's University City in Coyoacán.

On the way, we ran across murals in an unexpected place, Metro train stations. Our first encounter was a chance meeting with Ariosto Otero Reyes' revolutionarily themed mural in the Xola (pronounced, Shola) station on Line 2. This led us to research the existence of other Metro murals. We found a goodly number. We presented some that convey specifically revolutionary themes. Our post "Reverberations of the Mexican Revolution" explored how representations of themes of the Revolution spread out across the cityscape over the years.

But there are other Metro murals, some with themes we have seen before:

But there are other Metro murals, some with themes we have seen before:

|

| Encounter of the Cultures A primal theme for Mexico Mayan Mother Goddess Ixchel extends her hand—ala God to Adam in the Sistine Chapel— to European woman, also ala Leonardo DaVinci. Similar to the "New Adam" of Diego Rivera in San Ildefonso and the New Woman of Arturo García Bustos in the University Station mural, her force is atomic, a symbol we saw at the National University Map of Latin America from crest of National University. Graziella Scotese, Italian artist who came to Mexico in 1970s to study mural art. 1986 Station División del Norte, Line 3 |

|

| Civilización y cultura by José de Guimaraes (Portugese) Gift of the City of Lisbon 1996 An homage to such Mexican artists as David Alfaro Siqueiros, Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and Rufino Tamayo; and writers, including Sor Juana de la Cruz (17th century nun and poet), Octavio Paz and Juan Rulfo, among others. Upper right: Ancient symbol of world creation and destruction — two serpents eating each other's tails. Upper left: Aztec/Mexica jaguar warrior Chabacano Station, Line 9, where it intersects with Line 2 |

Crossroads in Space and Time

Because three lines meet at Tacubaya, it is a major Metro system crossroad. Multiple passageways had to be constructed to make possible the correspondencias, connections, between the three lines. This construction resulted in large spaces through which thousands of people pass daily. David Siqueiros, we think, would have been drawn to such a public space, where el pueblo, the people, go about their cotidianidad, daily life.

|

Passageways in Tacubaya Station |

Guillermo Ceniceros, Muralist Apprentice of David Siqueiros

Guillermo Ceniceros, an apprentice of Siqueiros, was attracted to this space. He was born in 1939 in a small pueblo in the state of Durango in northwest Mexico. but in 1951, when he was twelve, his family moved to the eastern city of Monterrey, in Nuevo León. When he was fourteen, he entered the Fabricación de Máquinas, S.A. (Manufacture of Machines, FAMA), a commercial school and business, where he studied industrial drawing.

Guillermo Ceniceros, an apprentice of Siqueiros, was attracted to this space. He was born in 1939 in a small pueblo in the state of Durango in northwest Mexico. but in 1951, when he was twelve, his family moved to the eastern city of Monterrey, in Nuevo León. When he was fourteen, he entered the Fabricación de Máquinas, S.A. (Manufacture of Machines, FAMA), a commercial school and business, where he studied industrial drawing.

In 1955, Ceniceros enrolled in the Taller de Arts Plásticas (Plastic Arts Workshop) at the Autonomous University of Nuevo León, graduating in 1958. He continued with FAMA and married fellow artist Esther González. In 1962, they moved to Mexico City where he obtained work with Luis Covarrubias painting ethnographic murals at the National Museum of Anthropology and History. During this project he also met artist Rufino Tamayo.

In 1965, David Alfaro Siqueiros hired Ceniceros to work on his murals of the Mexican Revolution at the National Museum of History in Chapultepec Castle. Subsequently, he worked on The March of Humanity on Earth and Toward the Cosmos at the Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum. In 1986, the Metro system hired Ceniceros to paint murals in the Tacubaya Station.

Returning to Mexico City's Founding Legend

In 1965, David Alfaro Siqueiros hired Ceniceros to work on his murals of the Mexican Revolution at the National Museum of History in Chapultepec Castle. Subsequently, he worked on The March of Humanity on Earth and Toward the Cosmos at the Siqueiros Cultural Polyforum. In 1986, the Metro system hired Ceniceros to paint murals in the Tacubaya Station.

Returning to Mexico City's Founding Legend

Rather than present images of the Revolution or visions of a future Mexico in the utilitarian, literally pedestrian space of Tacubaya Station, Ceniceros chose to go back to the indigenous origins of what is now Mexico City; that is, the legend of how some seven hundred years ago the Mexícas (Me-SHE-kahs) came to arrive in what was then the Valley of Anáhuac and found México-Tenochtitlán.

Legendary Beginnings: Emerging from Caves, Many Tribes Settle Around Lake with Island in the Middle

Legendary Beginnings: Emerging from Caves, Many Tribes Settle Around Lake with Island in the Middle

Nahuatl legends relate that, at the beginning of their history, seven tribes lived in Chicomoztoc, or "the place of the seven caves". Each cave contained a different Nahua-speaking group: the Xochimilca, Tlahuica, Acolhua, Tlaxcalteca, Tepaneca, Chalca, and Mexica. These groups are collectively called Nahuatlaca" (Nahua people) because of their common linguistic origin. In Mesoamerican legends of human origins, people are often created by emerging from caves—wombs of Mother Earth.

|

| Here (for some unknown reason), eight tribes are presented, around the lake of Aztlán |

These tribes subsequently left the caves and settled around Aztlán, an island in a lake. In his book "Fragmentos de la Obra General Sobre Historia de los Mexicanos" ("Fragments of the General Work About the History of the Mexicans"), Cristobal del Castillo (c.1458–1539) mentions that the lake around Aztlán was called Metztliapan or "Lake of the Moon."

While some legends describe Aztlán as a paradise, the Codex Aubin says that the Aztecs were subject to a tyrannical elite called the Azteca Chicomoztoca. Guided by their priest, the Aztecs fled, where, on the road, their god Huitzilopochtli forbade them to call themselves Azteca, telling them that they should be known as Mexica.

Ironically, scholars of the 19th century—in particular Alexander von Humboldt and William H. Prescott—would name them Aztec. Humboldt's suggestion was widely adopted in the 19th century as a way of differentiating "modern" Mexicans from pre-conquest Mexícas.

|

| Mexica on their migration In the backpack, the apparent child with beaked cap is a totem of their god, Huitzilopochtli. |

Some codici indicate that the southward migration began on May 24, 1064 CE. The "Anales de Tlatelolco" says the exit from Aztlán took place on "4 Cuauhtli" (Four Eagle) of the year "1 Tecpatl" (Knife), which correlates to January 4, 1065.

|

| Mexicas en route honor Huitzilopochtli |

Entering the Valley of Anáhuac and Mesoamerican History

The Mexicas were the last to arrive in the Valley of Anáhuac, sometime around the year 1248, nearly 200 years after their legendary departure from Atzlán. The shore around Lake Texcoco was fully settled. Each of the other six groups from Aztlán had arrived before them and founded an altepetl, a city-state, governed by a council of pipiltin, nobles, headed by an elected tlatoani, "speaker", chief) Thus, at this point, they also moved from legend into the recorded history of Mesoamerican civilization. Wikipedia

|

| Anáhuac Valley lakes, and altepetls, city-states, (left is north, right is south) Left-North: Lake Xaltocan Center: Lake Texcoco Right-South: Lakes Xochimilco and Chalco |

The most powerful of the altepetls were Culhuacan (on peninsula jutting from southeast (upper right) shore dividing Lake Texcoco from Lake Xochimilco), and Azcapotzalco on the west shore of Lake Texcoco (bottom, center of mural).

The Mexica first tried to settle in Chapultepec (just to south, i.e., right of Azcapotzalco). The Tepanecs of Azcapotzalco soon expelled the Mexicas. In 1299, the tlatoani of Culhuacan, Cocoxtli, gave them permission to settle in the empty lava beds of Tizapan (southwest of Coyoacán, lower right, now the area of the National University). In turn, they served as mercenary soldiers in his army, learning military skills they put to successful use some years later.

Island in Middle of a Lake Becomes Center of the World

According to Mexica legend, in 1323, they were shown a vision of an eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, eating a snake, indicating the place where they were to build their home. It may have been that they had been expelled from Culhuacan territory. They found the combination of snake-eating eagle on a cactus on a small swampy island in Lake Texcoco. In 1325, they founded the settlement of Tenochtitlán, "Prickly Pear among the Rocks"—reminiscent of the archetypical island of Aztlán in the middle of Lake of the Moon.

Island in Middle of a Lake Becomes Center of the World

According to Mexica legend, in 1323, they were shown a vision of an eagle perched on a prickly pear cactus, eating a snake, indicating the place where they were to build their home. It may have been that they had been expelled from Culhuacan territory. They found the combination of snake-eating eagle on a cactus on a small swampy island in Lake Texcoco. In 1325, they founded the settlement of Tenochtitlán, "Prickly Pear among the Rocks"—reminiscent of the archetypical island of Aztlán in the middle of Lake of the Moon.

|

| The Mexicas arrive on Tenochtitlán, "Prickly Pear among the Rocks" |

Fifty years later, their settlement was big enough to become an altepetl. In 1376, they elected their first tlatoani, Acamapichtli, son of a marriage between one of their leaders and a daughter of a tlatoani of Culhuacan. Despite its ties to Culhuacan, for the next 50 years, until 1426, Tenochtitlán remained a tributary of its closer neighbor, Azcapotzalco.

Upon the death of the Azcapotzalco tlatoani, Tezozomoc, in 1427, a series of power struggles broke out among the leaders of the altepetls subordinated to Azcapotzalco. In these struggles, Maxtla, son of Tezozomoc, killed Chimalpopoca, tlatoani of Tenochtitilan. In retaliation, his successor, Itzcoatl, allied with Nezahualcoyotl. the tlatoani of Texcoco (northeast side of Lake) and Totoquiatzin, tlatoani of Tlalcopan (aka Tacuba, west side of lake, between Chapultepec and Azacapotzalco).

In 1428, they defeated Maxtla. This coalition became what is known as the Triple Alliance, and Tenochtitlán became the dominant partner. Over the next 100 years, Tenochtitlán was to expand its domination over most of Central Mexico. Its tlatoani became huey tlatoani, "senior speaker," ranking him above the lords of subordinate altepetls.

In 1428, they defeated Maxtla. This coalition became what is known as the Triple Alliance, and Tenochtitlán became the dominant partner. Over the next 100 years, Tenochtitlán was to expand its domination over most of Central Mexico. Its tlatoani became huey tlatoani, "senior speaker," ranking him above the lords of subordinate altepetls.

|

| Tenochtitlán at its height, just before the Spanish arrived (viewed from the south; the lake is not to scale or actual form) Other Nahua altepetls around the lake are named. Tacubaya is lower left. |

|

| Left: First three tlatoani of Tenochtitlán, subordinate to Azcapotzalco: From left: Acamapichtli, Huitzilihui and Chimalpopoca Right: Six huey tlatoani, senior speakers of the Triple Alliance period Itzcoatl, Moctezuma Ilhuicamina (the Elder), Axayacatl, Tizoc, Ahuizotl, Moctezuma Xocoyotzin (the Younger) |

|

| Left: Cuauhtémoc, last huey tlatoani, executed by Hernán Cortés. Right: Leaders of the initial Triple Alliance Itzcoatl of Tenochtitlan Nezahualcoyotl of Texcoco Totoquiatzin of Tlalcopan/Tacuba |

Union of Political and Sacred Powers

|

| Tlacaelel I (1397 – 1487) portrayed as Eagle Warrior Principal architect of the Aztec Triple Alliance and hence of Mexica hegemony over Central Mexico. |

Tlacaelel: Mind Behind the Throne

During the war against the Tepanecs, Tlacaelel, nephew of tlatoani Itzcoatl, son of tlatoani Huitzilihuitl and brother of Chimalpopoca and Moctezuma I, was given the office of tlacochcalcatl (top general of the army), but after his great victory, he was named first adviser to the ruler, a new position called cihuacoatl. He held the office during the reigns of four consecutive tlatoani, until his death in 1487. His was the mind behind the throne.

It was Tlacaelel who rewrote the story of the Mexicas as a chosen people, elevated the tribal god Huitzilopochtli to the top of the pantheon of gods and promoted the State's militaristic identity. He is said to have increased the quantity and frequency of human sacrifice, particularly during a period of natural disasters that started in 1446 (Diego Durán, History of the Indians of New Spain, 1581). Durán also states that, during the reign of Moctezuma I, Tlacaelel invented the "Flower Wars", in which the Aztecs fought Tlaxcala and other city-states not to subdue them, but to collect captives for sacrifice. Wikipedia

|

Chac-mool Figure for receiving sacrificial offerings, human hearts.

(Name is modern, created by archeologists)

|

Blood Sacrifice: Fuel that Keeps Sun Turning and World Going On

The Aztec cosmos, like that of their Central Mexico predecessors, was believed to be kept going by the sacrifice of human blood to feed the Sun, so it would rise again each day, driving away the forces of darkness, the underworld and chaos through which it traveled in peril each night.

In Aztec mythology, there had been four previous "Suns", creations of the world, but they were unsuccessful and destroyed by various natural forces. The Fifth Sun, the Aztec world, was created in darkness at the site of Teotihuacan, the first major Mesoamerican city thirty miles north of Mexico City (See: Teotihuacan-Where the Gods Are Made). In order to get the Sun to rise and move across the sky once again, and hence for life and time to go on, a god had to sacrifice himself by jumping into a fire.

This cosmic event was ritualistically repeated in the New Fire ceremony held once every fifty-two years, when the beginnings of the 365-day solar calendar coincided with the 260-day divination calendar. The divination calendar was based on the length of human gestation and used to predict personal fate. The coincidence of the two calendars—of the cosmic cycle and human fate—made for a highly dangerous juncture; that is, at this juncture it was very possible that the Sun might not rise again and the era of the Fifth Sun would come to an end. The Stone of the Five Suns, in the National Museum of Anthropology and History, portrays this cosmology.

Sacrifice, of course, also kept in place the power of the State as the unique employer of "legitimate violence" (Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan).

Gods Who Rule

As we have seen, the Mexica, according to their legend, evidently as retold by Tlacaelel, came into existence as a people through the intentional act of a god, Huitzilopochtli, who separated them out from their cousin Aztec tribes, gave them their unique identiy and led them to a promised land.

The Mexica were initially nomadic hunter-gatherers. Upon their arrival in the Valley of Anáhuac, they first became part of a settled agrarian culture, then further developed into an urban civilization. Their many gods—originating in their hunting days or adopted by them from surrounding tribes when they settled down—likely reflect the various stages of their history.

The Wikipedia article on their mythology names two dozen or so godsHowever, as in the religions of many other cultures, gods and goddesses, primal forces of existence, can appear in various guises and bearing different names. Taken for granted in primal cultures, the "same" god or force can even appear in both male and female forms, confusing the "modern" mind that prefers neat categories.

Ceniceros portrays some of the Mexica gods on the walls of Tacubaya Station. There, they watch over modern Mexicans as they pass by, not unlike the saints on the walls of the city's many Catholic Churches.

The four cardinal directions are probably the earliest way available to human hunter-gatherers for creating their "world"; that is, as a means for organizing the terrestial space within which they roamed about. The four directions are marked by the Sun's East-West daily journey and, perpendicular to it, a North-South axis marked in the Northern Hemisphere by the North Star and the Big Dipper or Big Bear.

Nowadays, in Tacubaya Station, commuters—today's "hunter-gatherers"—follow yellow signs reading "Correspondencia a Linea 1, 7 or 9", Connection to Line 1, 7 or 9.

|

| Left: Tezcatlipoca, god

of twilight, ruler of the night, hence of the invisible, associated with the Great Bear constellation; hence, lord of the cardinal direction North. Right: Quetzalcoatl, the plumed serpent (a creature combining forces of earth and sky), god of light, life and wisdom. Associated with the morning star (Venus), lord of the East. |

|

| Mictlantecuhtli, god of the underworld, where death and chaos threaten human existence. Lord of the West |

The Mexica's Huitzilopochtli was originally a god of the Sun and, hence, Lord of the South, where the Sun rules.

|

| Left: Tlaloc, god of water Center: Chalchiutlicue, goddess of rivers and springs. (Ceniceros gives her a human visage. She would have had a symbolic one.) Ehécatl, god of the wind, who comes before the rains, announcing them. (critical for an agrarian culture with half-year-long dry and rainy seasons.) |

|

| Centeotl, goddess of corn (she would also have had a symbolic representation) Mayauel, goddess of maguey and pulque beer (likewise, she would have had a symbolic representation. We think Ceniceros has "westernized" these goddesses, ala classic Greek style) |

Gods of Familial and Tribal Conflict; hence, of History and War

|

| Coatlicue, goddess of human life. Serpent-headed, she gives life and takes it in death. The original statue is in the National Museum of Anthropology and History |

|

| Coyolxauhqui, daughter of Coatlicue She and her brothers kill their mother when they find her pregnant once again. Huitzilopochtli, the immaculately conceived child, son of the Sun, is born full-grown. He slays and dismembers his half-sister. She becomes the Moon, with its phases. Her brothers are chased into the heavens as stars. The original statue is in Museum of the Templo Mayor. |

|

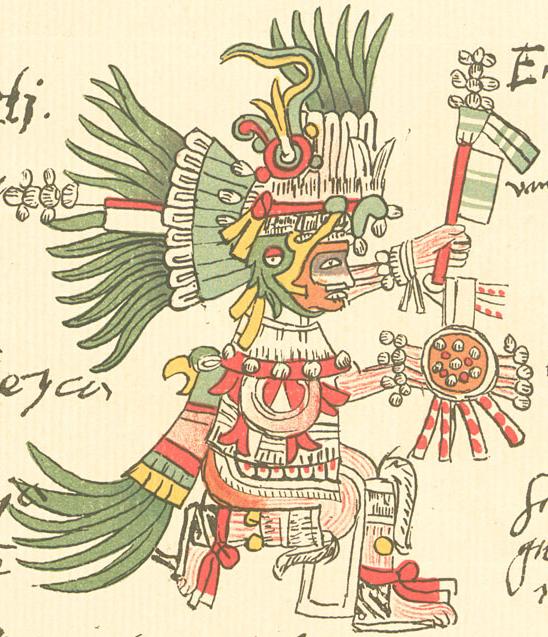

Huitzilopochtli, sun god and god of war. Lord of the south, Ceniceros' painting, portraying the god as a sun, is, paradoxically, in a dark corner, which we couldn't photograph. This 16th century representation is from Codex Telleriano-Remensis |

Postscript

Curiously, Ceniceros' largest mural in Tacubaya does not portray either a Mexica or Aztec personage or god. Set apart from the Mexica story, on a two-story high wall between two passageways, it is the jade death mask of a Mayan ahaw or lord, K'inich Janaab' Pakal I, Great Sun Lord Shield, of Palenque, who reigned from 615 to 683 CE. The Maya were, of course, the other major indigenous civilization in what is now Mexico.

The Maya city-states, south of the Isthmus of Tehuantepec—far from Central Mexico but in trade relations with it—had their heyday during the so-called Mesoamerican Classic Period, from about 300 to 800 CE. They emerged during a political hiatus and resulting power vacuum that took place in Central Mexico between the decline of Teotihuacan (ending around 500 CE) and the rise of a successor power, the Toltecs in Tula, Hidalgo, north of Teotihuacan (800 to 1200 CE).

The rise of the city-states in the Valley of Anáhuac came with the decline of Toltec power. The Mexicas were the last of a long series of dominant powers.

|

| Jade death mask of Mayan lord Pakal I |

Ceniceros's Other Murals

Guillermo Ceniceros has created over fifteen other large-scale murals in public places in Mexico City, Monterrey (his "home town") and his home state of Durango, as well as in the Mexican Mission to the United Nations in New York City. A few years after recreating the history of the Mexicas and Teotihuacan in the Tacubaya Station, Ceniceros undertook portraying an even grander concept in an even larger space, in Copilco Station on Line 3. That, if you'll forgive the pun, is our next stop.

Now 77, Ceniceros continues to live in Mexico City at his studio/home in Colonia Roma.